Diagnosis of Psoriasis in Hard-To-Treat Body Locations

Introduction

Inflammatory pathology represented by psoriasis vulgaris is much more than a simple skin condition and is a global health problem. Psoriasis for many patients results in a marked functional, psychological and social morbidity. The concept of psoriasis severity refers to many different aspects of psoriasis, including the extent of the disease, the location of the lesions, the degree of inflammation, the ability to respond to treatment and the impact on quality of life. Thus, patients with any type of psoriasis require an assessment of the severity of the disease, the impact of the disease on physical, psychological and social condition, diagnosis of the existence of psoriatic arthritis or other comorbidities. Overall assessment of the patient, assessment of the affected body surface, nail damage, affected areas with high impact and difficult to treat, or any systemic disorder such as fever, malaise, which are common in unstable forms of psoriasis such as erythroderma or generalized pustular psoriasis [1].

Psoriasis is a chronic, multisystemic disease with many comorbidities, which is often difficult to treat, and some cases may be refractory to treatment. Total eradication of plaques is difficult to achieve, and the remission time is short. Recurrence is inevitable and is often preceded by poor adherence to topical therapy. Forms of gouttate psoriasis may resolve spontaneously or may progress to chronic plaque psoriasis. Erythrodermic psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis can be life-threatening if left untreated and recurrences are common [2]. The clinical form of psoriasis in plaques refers to the form of well-defined erythematoussquamous plaques, “salmon-pink” to bright red, covered with thick, multilayered, non-adherent silvery white or gray-white scales. Brocq’s methodical maneuver highlights the whitening and fragmentation of the scale, and the detachment of the last layer of scales can objectify a punctiform bleeding (Auspitz sign) due to the phenomenon of papillomatosis. The annular or arched appearance may appear through the central resolution of the plaques and the confluence of the small plaques may determine the appearance of a geographical map.

The common locations are represented by the extension areas of the limbs (knees, elbows), the lumbosacral area, the scalp or the umbilical region. Clinically form of gouttate psoriasis presents multiple, round, small lesions (0.5-1 cm in diameter) (Figures 1a-1f), particularly on the trunk and upper limbs, with rapid extension, being a common form in children and young adults. Inverted (flexural) psoriasis has erythematous plaque lesions, with fine scales, in the major genito-crural, axillary and submammary folds [3]. Healthcare professionals and patients using the term psoriasis usually refer to plaque psoriasis and unless otherwise stated. The term “difficult-to-treat areas” usually refers to the face region, flexion areas, genitals (affected in 45% of cases), scalp, palmoplantar region and are so named because psoriasis in these places can have a significant impact and can lead to functional impairment and require carefully selected topical therapy, which may be resistant to treatment [4].

Figure 1: Clinical aspects of psoriasis vulgaris: erythematous-squamous plaques located on the extension areas of the ulnar region (a), knee (b), forearm (c), scalp (d) and psoriatic onychopathy with leuconiquia, distal onycholysis and longitudinal ridges (e), with the appearance of “oil stains” index and middle accompanied by skin lesions on the dorsal faces of the hands (f).

The scalp is one of the most common sites for psoriasis, usually with well-defined individual erythematous-squamous plaques, which often which usually extend about 1 cm beyond the hairline and advance to the cervical, retroauricular and facial regions, accompanied by pruritus and discomfort. Scalp psoriasis does not usually induce alopecia and the most common differential diagnosis of scalp psoriasis includes seborrheic dermatitis, tinea capitis and lichen planopilaris [5]. In addition, dermatomyositis involving the scalp may have lesions similar to psoriasis [2]. Flexural or inverse psoriasis is characterized by erythematous, shiny, smooth, well-defined plaques, the scales are not clearly visible due to the characteristic moisture in the folds and common topographic areas include the axillary area, sub mammary folds, groin and intergluteal fold. Inverse psoriasis is less common than plaque psoriasis and is estimated to affect 3-36% of patients [6]. In infants, it can often occur in the diaper area, with a typical damage to the groin folds, also known as napkin psoriasis. Common differential diagnoses include bacterial or Candidiasis intertrigo, tinea cruris, contact dermatitis, fold eczema and Hailey-Hailey disease [1].

Genital psoriasis affects up to 60% of patients throughout life [7] and can have a significant impact on patients’ psycho-social function due to physical symptoms such as itching and local pain, with a negative impact on sexual health [1]. As with inverse psoriasis, the scales are discrete or absent, and painful fissures in the intergluteal fissure and intense erythema can be a diagnostic argument. Vulvar psoriasis requires differential diagnosis with atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, sclero-atrophic lichen, lichen planus and premalignant lesions [8]. In men, irritative balanitis, Zoon balanitis, Queyrat erythroplasia or extramammary Paget’s disease can mimic genital psoriasis [8]. When nail changes or typical erythematous-squamous lesions of psoriasis are missing elsewhere in the body, skin biopsy may be helpful in establishing a certain diagnosis. The motivation of the study is given the importance of the need to outline the epidemiological profile of psoriasis which affects the quality of life through psycho-emotional impact and hard to treat body locations.

Materials & Methods

We performed a retrospective epidemiological study of 527 hospitalized patients diagnosed with psoriasis vulgaris in the Dermatological Clinic of the Emergency County Clinical Hospital “Saint Spiridon”, Iasi in order to establish the frequency of major forms of psoriasis and describe the characteristics demographics such as gender distribution, age group and hard to treat body locations in psoriasis. The collection of information from the observation sheets complied with both the type of information collected for each patient and the time intervals at which they were obtained. Criteria for inclusion in the group of patients with inflammatory pathology included patients with main clinical and/ or histological diagnosis with psoriasis vulgaris hospitalized in the Dermatology Clinic within the County Emergency Hospital “Saint” Spiridon in Iasi, during 1.01.2016-31.12.2019 for 4 years, patients whose observation sheets or electronic files contained sufficient information to make them relevant to the study. Exclusion criteria were represented by patients whose observation sheets or electronic files did not contain sufficient information to make their inclusion in the study possible.

After applying the selection criteria, a series of 527 patients was created that met all the specified conditions. The information was collected from computer databases and patient observation sheets and included a number of variables relevant to the research. Variables analyzed in the group with psoriasis vulgaris were represented by gender (female or male), age, clinical form of psoriasis (plaque psoriasis, gouttate psoriasis, palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, generalized pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, plaque and gouttate psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, inverse and gouttate psoriasis, psoriasis vulgaris in plaques, gouttate and inverse psoriasis, pustular and inverse psoriasis vulgaris, gouttate psoriasis and pustular psoriasis). Similarly, hard to treat locations distribution such as scalp, palmoplantar area, nails, genital region, large folds, face were analyzed. Quality of life was assessed using standardized Daily Life Quality Index (DLQI) severity score through questionnaire which revealed following values: 0-1 = no effect on the patient’s quality of life; 2-5 = low effect on the patient’s quality of life; 6-10 = moderate effect on the patient’s quality of life; 11- 20 = important effect on the patient’s quality of life; 21-30 = very important effect on the patient’s quality of life.

In order to carry out retrospective studies subsequently, we coded this information in order to be able to enter it in a database with parametric and non-parametric data that we analyzed statistically. The statistical analysis of the data was performed with the software STATISTICA ver. 7.0. Depending on the needs of the statistical analysis, the data were used either in the original version or were grouped according to some classification criteria imposed by methodologies, or established according to the type and particularities of the variables included in the analyzes. We analyzed the differences between the mean values according to the grouping variables, using the t test for independent samples according to the grouping variables sex and environment of origin, appreciating as significant the differences located at a significance threshold p <0.05. The significance of the differences between the frequencies was evaluated with the help of the χ2 test, appreciating as significant the differences when the calculated value of the χ2 test will be higher than the critical value corresponding to the significance threshold p = 0.05. If percentages were compared, the significance of the differences was assessed using the Z test, assessing as significant the differences located at a significance threshold p <0.05.

The present study was carried out in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments and was approved by the Ethics Commission of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Grigore T. Popa” Iasi and by the Ethics Commission of the Emergency County Clinical Hospital “Saint Spiridon”, Iași, through the ethics opinion in accordance with the Research Law no. 206 of 27 May 2004 on good conduct in scientific research, technological development and innovation, as well as with the European legislation in force (European Regulation 679) on the processing of personal data. The rights to integrity and confidentiality of the subjects included in the study were respected.

Results

Frequency of Cases with Special Impairment, Depending on Age Groups

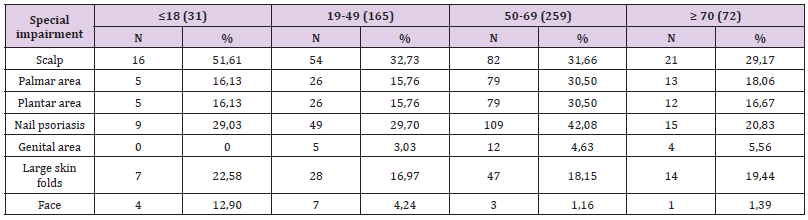

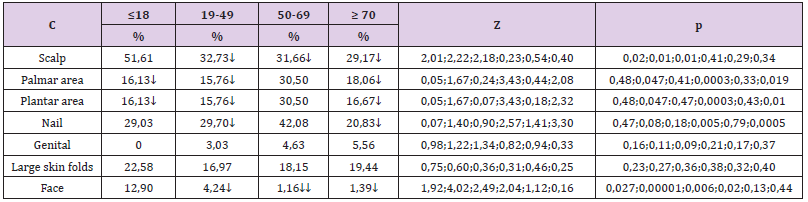

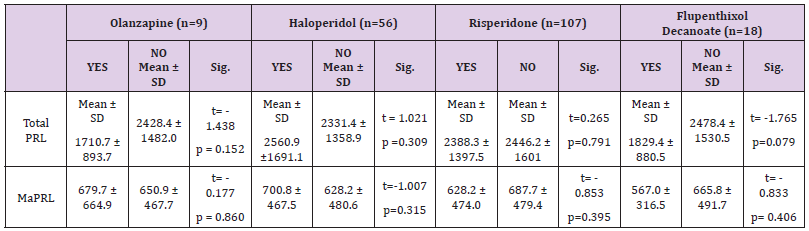

To compare the frequency of cases by age groups by sex, the Z test was used to compare the percentages of two different populations (in our case men and women), at the minimum significance threshold p <0.05. The study included a number of 527 patients diagnosed with psoriasis vulgaris, with a distribution by age groups showing 229 women and 298 men, with 49.15% of the total number of the group , respectively 288 patients with urban background. After comparing the frequency with which special impairments occurred by age groups, the following (Tables 1 & 2) significant differences were obtained:

a) The frequency of scalp psoriasis was significantly higher in patients aged ≤18 years (51.61% compared to 32.73% aged 19-49 years, Z = 2.01, p = 0.02; compared to 31 , 66% aged between 50-69 years, Z = 2.22, p = 0.01; compared to 29.17% aged ≥ 70 years, Z = 2.18, p = 0.01);

b) The frequency of palmar involvement was significantly higher in patients aged 50-69 years (30.5% compared to 16.13% aged ≤18 years, Z = 1.67, p = 0.047; compared to 15.76 % aged 19- 49 years, Z = 3.43, p = 0.0003; compared to 18.06% aged ≥ 70 years, Z = 2.08, p = 0.019);

c) The frequency of plantar involvement was significantly higher in patients aged 50-69 years (30.5% compared to 16.13% aged ≤18 years, Z = 1.67, p = 0.047; compared to 15.76 % aged 19- 49 years, Z = 3.43, p = 0.0003, compared to 16.67% aged ≥ 70 years, Z = 2.32, p = 0.01);

d) The frequency of nail psoriasis was significantly higher in patients aged 50-69 years (42.08% compared to 29.7% aged 19-49 years, Z = 2.57, p = 0.005 and compared to 20 , 83% aged ≥ 70 years, Z = 3.30, p = 0.0005);

e) The frequency of facial extension was significantly higher in patients aged ≤18 years (12.9% compared to 4.24% aged 19- 49 years, Z = 1.92, p = 0.027, compared to 1.16 % aged between 19-49 years, Z = 4.02, p <0.00001 and compared to 1.39% aged ≥ 70 years, Z = 2.49, p = 0.006); it was found that the frequency in patients aged 19-49 years was significantly higher than that of patients aged 50-69 years (4.24% compared to 1.16%, Z = 2.04, p = 0.02). 3.2. The relationship between the clinical form of psoriasis and the special condition:

To see if a particular clinical form of psoriasis is significantly associated with a particular special condition, it was necessary to compare the frequencies of each special condition with all the others in each clinical form of psoriasis. In order to be able to make those comparisons, it was necessary to convert the gross frequencies of each special affectation into percentage frequencies by relating them to the total cases of each corresponding special impairment, the result of which was then multiplied by 100. The differences between the percentages were tested with Z test, being considered significant those differences that were located at a significance threshold p <0.05.

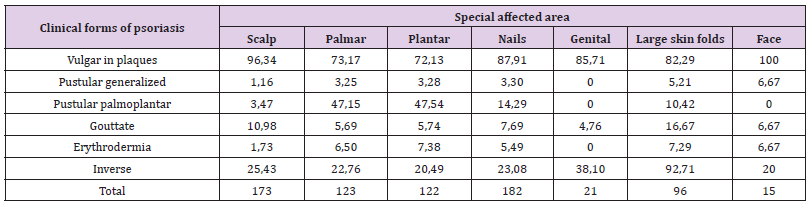

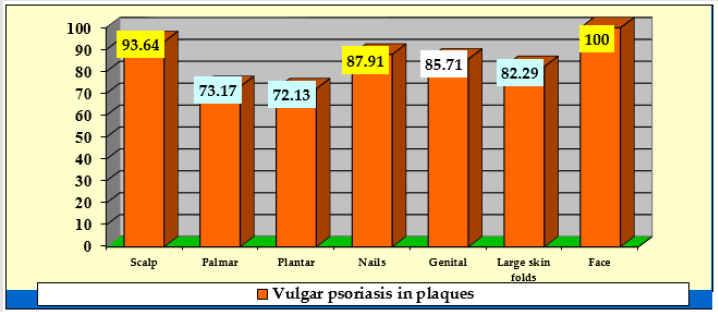

Comparison of the incidence of special conditions in patients with plaque psoriasis (Table 3, Figure 2) showed that:

a) Facial psoriasis (100% of cases) was significantly more common compared to: 73.17% in the palmar area, Z = 2.3, p = 0.01; 72.13% in plantar area, Z = 2.36, p = 0.009 and 82.29% in large folds, Z = 1.77, p = 0.038;

b) Scalp involvement (93.64% of cases) was significantly more common compared to: 73.17% in the palms, Z = 4.88, p <0.00001; 72.13% in plants, Z = 5.06, p <0.00001; 87.91% for nails, Z = 1.86, p = 0.03 and 82.29% for large folds, Z = 2.92, p = 0.0017;

c) Nail psoriasis (87.91% of cases), was significantly higher than: 73.17% in palms, Z = 3.28, p = 0.0005 and 72.13% in plants, Z = 3, 48, p = 0.00025;

d) The involvement in the area of large folds (82.29% of cases) was significantly higher than 72.13% in plants, Z = 1.76, p = 0.04.

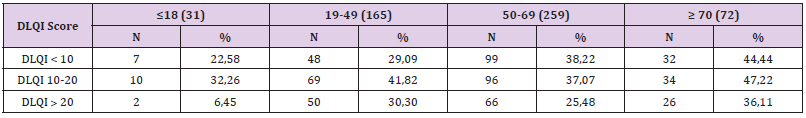

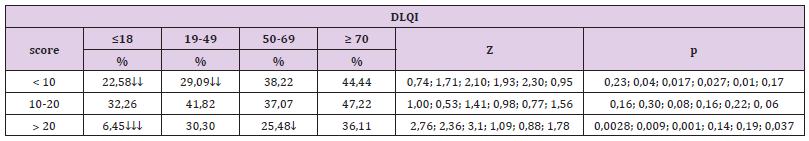

In patients with inverse psoriasis it was also observed that the frequency of cases with psoriasis of genital area was significantly higher, 38.1%, compared to 20.49% with plantar area, Z = 1.77, p = 0.038. 3.3. Comparison of the frequency of cases with DLQI scores <10, between 10-20 and higher than 20 (Tables 4 & 5): In the four age groups, the results highlighted the following significant differences:

a) The frequency of cases with DLQI scores <10, was significantly higher in patients aged 50-69 years (38.22% compared to 22.58% of those aged ≤18 years, Z = 1.71, p = 0.04 and compared to 29.09% of those aged 19-59 years, Z = 2.10, p = 0.017) and those aged ≥ 70 years (44.44% compared to 22.58% of those aged ≤18 years, Z = 1.93, p = 0.027 and compared to 29.09% of those aged 19-49 years, Z = 2.3, p = 0.01); the frequency of cases with DLQI scores between 10-20, did not differ significantly depending on the age groups;

b) The frequency of cases with DLQI scores> 20, was significantly lower in patients aged ≤18 years (6.45% compared to 30.03% of those aged 19-49 years, Z = 2.76, p = 0.0028, compared to 25.48% of those aged 50-69 years, Z = 2.36, p = 0.009, compared to 36.11% of those aged ≥ 70 years, Z = 3.10, p = 0.001); the frequency of cases with DLQI scores> 20 was significantly higher in patients aged ≥ 70 years compared to those aged 50-69 years (36.11% compared to 25.48%, Z = 1.78, p = 0.037 ).

Discussion

Psoriasis is a major global health problem with an increased prevalence with values ranging from 0.09% [9] to 11.4% [10] with a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Clinical examination and evaluation through several tools that quantify the quality of life, such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Cutaneous involvement of the scalp, face, palms, soles, nails and mucosal involvement such as genitals can be particularly debilitating [11]. Few available research on patients with psoriasis in hard-to-treat locations were based on large study populations with psoriasis. The main objective of this study was to describe patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics, disease severity, and quality of life impacts in patients with hard-to-treat body locations of psoriasis. We investigated the prevalence of hard-to-treat body locations of psoriasis, and similarly we described patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics. In the current retrospective study, the analysis of the total number of hospitalizations (527) in relation to the distribution by sex showed that each year the percentage was higher in men, the percentage frequency differences between the sexes being due to the higher number of men (298) compared with that of women (229).

Gender differences in the characteristics of skin conditions can be influenced by complex interactive mechanisms involving the effect of anatomy, physiology, immunity, genetics, epigenetics, sex hormones, ethnic background, as well as geographical, sociocultural and environmental factors. Epidemiological data reported in the literature show that psoriasis is considered equally prevalent in both sexes [12]. However, of all the studies that reported prevalence by sex, some indicated that psoriasis is more common in men [13], but the values quoted are not statistically significant, and others indicate that psoriasis appears to be less common or more widespread among women than among men [14], so further studies and investigations are needed to differentiate genetic and behavioral factors. The age distribution of the clinical forms of psoriasis vulgaris in the group of patients analyzed showed that the frequency of gouty psoriasis associated or not with erythematoussquamous plaque lesions appeared significantly higher in patients aged 18 years or less, aspects confirmed in the literature as well [15].

Psoriasis was subclassified according to the age of onset and thus psoriasis with early onset (also called type I) can occur before the age of 40, with maximum onset at the age of 16-22. Late-onset psoriasis, also called type II psoriasis, has onset at or after the age of 40, with a maximum age of onset between 57 and 60 years [16]. Other epidemiological studies indicating that the average age in patients with pustular psoriasis is reported between 48 and 50 years [17]. Another significant difference was found in patients aged ≥ 70 years in whom the frequency of reversed psoriasis appeared significantly higher with vulgaris and pustular psoriasis (98.61% compared to 92.28% in those aged 50-69 years). There is a relationship between plaque and pustular psoriasis, as some people may have episodes of plaque psoriasis that precede or follow pustular lesions, the most common trigger factors being viral or bacterial infections or improper use of corticosteroid therapy. This higher frequency may also be due to the fact that as the population of people over the age of 65 in the world continues to grow, the incidence of older people suffering from psoriasis will also increase proportionately.

Patients with the clinical form of plaque psoriasis had as the most common special location to the scalp (93.64% of cases) compared to the palmo-plantar, nail or flexural region. Psoriasis located in areas difficult to treat has a negative impact on quality of life. Thus, studies show that up to 80% of psoriasis patients develop scalp psoriasis and up to 97% of affected individuals reported that the disease affects their daily lives [18]. The frequency of facial and scalp damage was significantly higher in patients younger than 18 years and aged 19-49 years than in patients aged 50-69 years. Scalp is one of the most common sites for psoriasis and facial damage occurs at one time in about half of those affected by psoriasis. Thus, in young, active patients, the damage to these special areas by the unsightly presence of erythematous-squamous lesions on very visible areas often causes psychosocial problems. Common chronic conditions such as psoriasis may be associated with increased psychological distress [19]. Psoriasis is associated with low selfesteem, anxiety (30%) and depressive disorders (60%) [20].

The treatment of psoriasis can promote the relief of depression both due to decreased psychodynamic problems and the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), aspects that need to be considered during therapeutic decision-making [21]. In the presence of these multiple possible comorbidities, the optimal management of the patient with psoriasis vulgaris consists in the holistic approach and the interdisciplinary approach [22]. After comparing the frequency with which special impairments occurred by age groups, it was obtained that the frequency of palmoplantar involvement was significantly higher in patients aged 50-69 years. Although palmoplantar psoriasis is a disabling variant of psoriasis and therapeutically challenging condition its epidemiology is poorly defined [23,24]. Palmoplantar psoriasis can occur at any age. Statistically analyzed data are according to available data from a systematic review and meta-analysis [25] which included a total of 2083 patients with palmoplantar psoriasis (1072 men and 841 women) and the ages of the patients ranged from 8 to 87 years, while the mean age ranged from 37.4 years to 58.5 years. With the exception of two studies, all studies reported a clinical type of palmoplantar psoriasis with hyperkeratosis, pustular or mixed plaques, and the most common was the type of hyperkeratosis plaque [25].

Also in this age group between 50-69 years the frequency of nail damage was significantly higher than those aged 19-49 years (42.08% compared to 29.7%). Literature review shows that men and women are equally affected by nail psoriasis, and its prevalence increases with the age of the study population [26]. Results from a Danish skin cohort with a total of 4016 adults with psoriasis showed that the most frequently affected hard-to-treat area was the scalp (43.0%), followed by the face (29.9%), nails (24.5%), soles (15.6%), genitals (14.1%), and palms (13.7%) [27]. Similarly to our study results, higher prevalence was generally seen with increasing psoriasis severity and patients with involvement of certain hard-totreat areas such as hands, feet, and genitals had clinically relevant DLQI impairments. Psoriasis is no longer considered just a skin disease, but rather a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that presents a substantial risk in increasing the rate of comorbidities [28]. Nail damage is an important problem in dermatological practice, and nail psoriasis may be present alone or may be associated with other skin lesions.

The nail involvement (87.91% of cases) was significantly higher than the palmoplantar area, and the damage in the area of large folds (82.29% of cases) was significantly higher than 72.13 % of the plantar area. Nail psoriasis has been reported in 10-80% of patients with psoriasis, with nails psoriasis on the upper limbs being more often affected than those on the lower limbs. Moreover psoriasis is a common cause of disturbance of the nail morphology and may be associated with all clinical forms of disease [29]. The importance of nail psoriasis was studied, and in a survey in the Netherlands, 79% of patients reported nail involvement, 52% suffering from associated pain and 14% having major restrictions in daily life due to changes in the nail apparatus [2]. Currently, the association of an inflammation of the nail bed has a prevalence between 10-80% recorded in patients with psoriasis [2]. The anatomical connection between the last phalanx and the nail unit determines the correlation between arthropathic psoriasis and nail changes [30].

Some manifestations of psoriasis are associated with an increased risk of developing other manifestations, for example, psoriatic arthropathy in patients with psoriasis with manifestations on the scalp and nails [31]. Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder characterized by joint inflammation with a prevalence of 0.05% - 0.25% of the population and 6% to 41% of patients with psoriasis [32]. Although nail psoriasis is usually investigated by clinical examination, the diagnosis of incipient form of disease is needed. Patients with nail damage appear to have an increased incidence of psoriatic arthritis [33]. In the present study, out of the 527 patients with psoriasis, 98 patients presented different clinical forms of onychopathy (18.6%), a result that falls within the range reported in the literature. In our study the frequency of cases with psoriasis of genital area was significantly higher, 38.1% in patients with flexural psoriasis compared to 20.49% with plantar area, Z = 1.77, p = 0.038. Similarly, Kelly, et al. [34] reported that psoriasis involving the genital area occurs in up to two-thirds of psoriasis patients but is often overlooked by physicians.

Furthermore, often the impact this small area of psoriasis can have on a patient is neglected. It can have a significant impact on patients’ psychosocial function due to intrusive physical symptoms such as genital itch and pain, and a detrimental impact on sexual health and impaired relationships. Analysis of the distribution of DLQI values according to age groups showed a higher quality of life impairment in patients older than 70 years.

Conclusion

Hard-to-treat areas in psoriasis are represented by the scalp, face, palms, soles, nails and genital areas. The burden of disease may be due to high frequency of hard to treat body locations such as the facial and scalp regions at early age. Inverse psoriasis has frequently genital area involvement and consequently leads to a negative impact on patiens quality of life. Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the acquisition of the data and critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. AIP, DTO conceived review on dermoscopy. IAH and LGS conducted the retrospective study and contributed to statistical analysis and results interpretation. LS, IAP, DV and EPA wrote and conceived the manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.