Predictors of Mortality Among Children Co-Infected with Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Region, North Ethiopia, Retrospective Follow- Up Study

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

co-infection remain a major global and national health problem

that requires substantial action to achieve the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDG) and the END-TB strategies [1]. Both TB

and HIV are the leading causes of death from infectious diseases

worldwide [2]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV co-infection in

the human body, potentiate each other and accelerate to death by

deteriorating body immunity causing premature death if untreated

[3]. Tuberculosis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in

HIV-infected children [4]. In 2015, the World Health Organization

(WHO) report showed that nearly 41,000 children died from TB and

HIV co-infection. Of which more than 83% were occurred in Africa

[5]. Mortality among children co-infected with TB and HIV varied in

different settings and fluctuated widely from 6.2% to 36.5% [5-7].

In Ethiopia, mortality of children co-infected with TB and HIV was

14% [8] and co-infected children had six times greater death than

TB disease alone [9]. Furthermore, more than 1 in 5 TB and HIV coinfected

individuals were died [10], but this huge problem was not

specifically known in children.

The prevalence of TB and HIV co-infection in children was

under-assured due to the problem of reaching a definitive

diagnosis. However, the WHO report showed that HIV prevalence

among children with active TB disease ranges from 10 to 60%,

depending on the background rates of HIV infection in countries

with moderate to high prevalence of TB [11]. The estimated rates of

tuberculosis among HIV positive children also had a wide variation,

depending on the TB epidemic and the coverage of highly active

antiretroviral treatment (HAART) coverage in the area [4].

Data on the survival of TB and HIV co-infection in children

are still lacking and the available information is difficult to

interpret due to problems with the diagnosis and selection of

study populations [4]. In developing countries, including Ethiopia,

the management of TB and HIV co-infection in children is very

challenging due to the inaccessibility of appropriate formulations

of drugs, drug-drug interactions, pill burdens, drug side effects, and

poor drug adherence [12-14]. This may result in high TB incidence

and mortality among HIV-positive children. TB is not only the most

commonly reported opportunistic infection [15], but also a major

cause of hospital admission and death in HIV infected children

[16]. The cause of death is also multifactorial and determined by

socio demographic, clinical, laboratory, drug and follow-up related

factors [8]. Which are poorly understood. Therefore, studies on

mortality and its predictors in TB and HIV co-infection in children

are very significant to designate appropriate action according to

their ages.

Most of the studies on TB-HIV co-infection focused on adult,

fewer studies on general co-infected population, little is known in

pediatrics sub-age group. Still, the problem in children is masked

and actions are taken based on findings from studies in the adult

population. However, the problem is very alarming in children

due to immature immune system and fast deterioration into death

[17,18]. A previous study in the comprehensive specialized hospital

of Gondar University in Ethiopia lacks a time specification on the TB

and HIV co-infection period, rather they prolonged their follow-up

after TB was cured. This makes the study more biased.

To some extent, there is better evidence on the incidence and

predictors of tuberculosis in HIV-infected children [19,20], but

evidence on survival and mortality after co-infection is limited in

Ethiopia. Therefore, survival and predictors of mortality among

children co-infected with TB and HIV have not been well documented

in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was to try to fill the above gaps by

estimating survival and identifying predictors of mortality among

children co-infected with TB / HIV in public general hospitals in

Mekelle and the southern zone of Tigray region, northern Ethiopia.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Period

A retrospective hospital follow-up study was conducted in two zones of the Tigray Region (Mekelle and Southern), which is located in the northern part of Ethiopia by reviewing 10 years (2008- 2018) medical records of children co-infected with TB and HIV in 2019. About 1,179,687 populations lived in these two zones. Of which 515,524 were children [21]. The study was conducted from October 1,2018 to June 30, 2019 in three selected general hospitals (Mekelle, Alamata, and Maychew).

Population and Sampling

Source Population

All children infected with TB and HIV co-infected under 15 years of age who received follow-up care from January 1 / 2008 to December 30/2018 in the ant-retroviral treatment (ART) clinic at public general hospitals of the Mekelle and southern zone of the Tigray region, North Ethiopia.

Study Population

All children co-infected with TB and HIV, under 15 years of age and those who followed up from January 1 / 2008 to December 30/2018 in the ART care clinic of selected hospitals in the study area.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Children infected with TB-HIV co-infected younger than 15 years were included in this study and had follow-up care from January 1/2008 – December 30/2018 in a selected hospital. Children who had missed key information on clinical, immunological, drug information and their outcomes had not been recorded on medical charts were excluded.

Sampling Technique

In the Mekelle and Sothern zones of the Tigray region, five general hospitals were found to provide ART services. These are the general hospitals of Mekelle, Quiha, Maychew, Alamata, and Korem. However, this study used cluster sampling by randomly selecting three hospitals (Mekelle, Alamata, and Maychew). Since we used cluster sampling, all children co-infected with TB and HIV who were enrolled in selected hospitals in two zones who met the inclusion criteria were included. The medical charts of children with TB and HIV co-infected from 2008 -2018 were reviewed.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected from medical records (charts) using a data

extraction checklist developed from the national HIV intake and

follow-up form [22]. The checklist consisted of sociodemographic,

clinical, and HIV care/ART/ follow-up related information. Data

were collected from April 15/2019 to May 20/2019 from medical

records. If the child is co-infected with TB and HIV, the follow-up

should continue for the entire life (for HIV care) even if the child was

cured from TB. After verifying completeness and consistency, the

data were coded and entered into Epi-data manager version 4.4.2.1

and then exported to Stata version 14 for analysis. Kaplan–Meier

survival graph and Log-rank test were used to compare the survival

difference between intragroups of categorical variables. Mortality

rate, person-time observation, and mean survival time were

calculated by Stata. The Cox proportional hazard model was used

for analysis. The Schoenfeld residual test (estat phtest) or global

test was used to check the Cox proportional hazard assumption, it

was non-significant (Prob>chi2 = 0.4179) indicates the hazard was

proportional over time. Regarding multi- collinearity, the mean VIF

was 1.39 indicates, collinearity between variables was within the

acceptable range.

Both bivariate and multivariate analysis was computed to

determine the association between predictor variables and the

outcome variable. These variables that were significantly associated

with a p-value of <0.2 in the bivariate analysis were entered into

the multivariate analysis. Variables significantly associated with

the outcome variable at a p-value <0.05 in the multivariate analysis

were considered independent predictors of mortality. Finally, the

adjusted hazard ratio with 95% CI and P value was used to measure

the significant association between predictors and outcome

variable.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was evaluated and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Mekelle University, a college of health sciences, and then ethical clearance was obtained. A cooperation letter was written to the chief executive managers of each hospital. Since the study was retrospective and document review, it did not cause any risk to the study participants.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

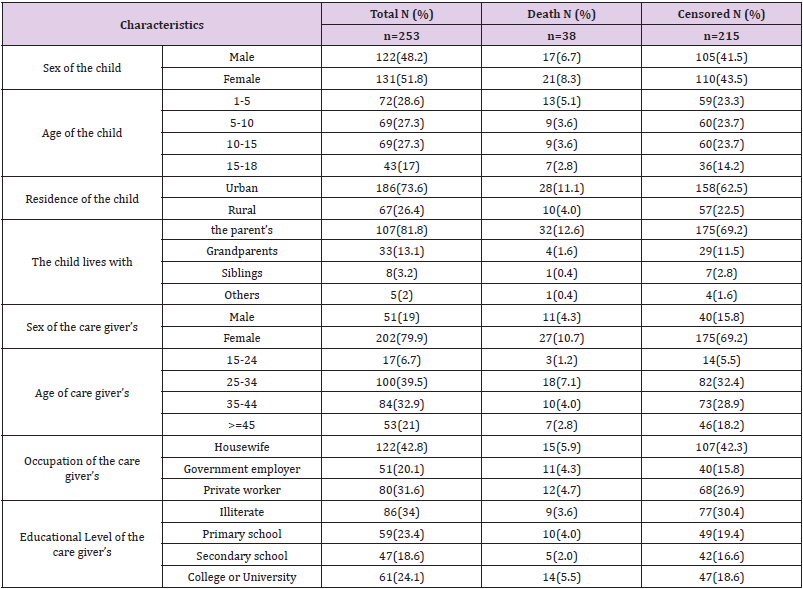

A total of 282 children with co-infected TB and HIV were enrolled in the general hospitals of Mekelle, Alamata, and Maychew. Of which 29 were excluded from the study due to lost cards or incomplete data. The remaining 253 children co-infected with TB and HIV were included in the study. The median age of the study participants was 8 years with IQR (4-13). One hundred and thirtyone (51.8%) of the children were females (Table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of children co-infected with TB and HIV in general hospitals of two zones of the Tigray region, North Ethiopia, 2019 (n=253).

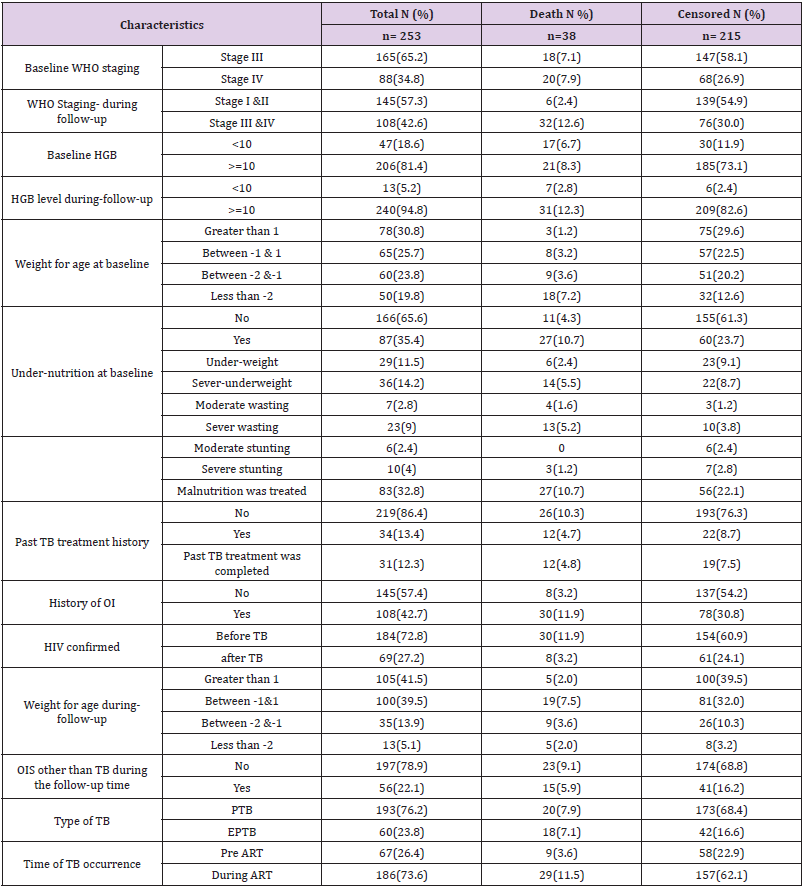

Clinical and Immunological Related Characteristics

Of a total of 253 children co-infected with TB and HIV, 186 (73.6%) of them developed TB after starting ART. At baseline, 165 (65.2%) of the children co-infected with TB and HIV had WHO stage III, and 129 (51%) had a CD4 count of less than 350 with a median of 330 cells (IQR (176.50-519.50)) cells/μl. During followup, 145 (57.3%) of the children co-infected with TB and HIV had improved their WHO staging to stage I & II. However, 66 (26.2%) of the children had a CD4 count of less than 350 with a median of 540 IQR cells (322.50-840.50) cells/μl. Thirteen (5.2%) of the children had anemia (HGB <10mg/dl) with a median HGB level of 13 (IQR (12-14.4)) mg/dl (Table 2).

Table 2: Clinical and immunological characteristics among children co-infected with TB and HIV in general hospitals of two zones of the Tigray region, North Ethiopia, 2019 (n=253).

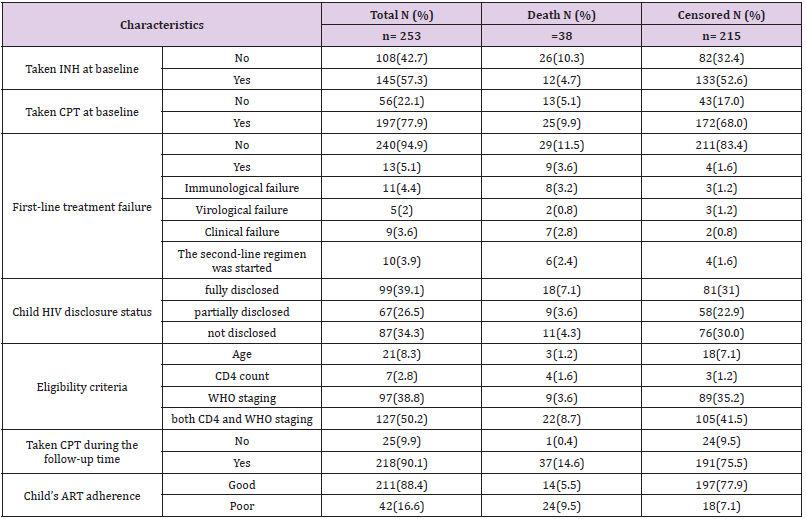

Education and Follow-Up Related Characteristics

One hundred and ninety-seven (77.9%) of the respondents had taken co-trimoxazole preventive therapy and 145 (57.3%) had also taken isoniazid preventive therapy before developing TB. The initial ART regimen was changed in 59 (23.3%) of the children due to side effects 35 (13.9%), TB 9 (3.6%), treatment failure 13 (5.1%) and other reasons 4 (1.6%) such as drug toxicity. Firstline ART treatment failure was observed in 13 (5.1%) children. Of these, 10 (76.9%) of them initiated second-line ART regimens. Regarding ART adherence, 211 (88.4%) of the children had good ART adherence (Table 3).

Table 3: Medication and follow-up related characteristics among children co-infected with TB and HIV in general hospitals of two zones of the Tigray region, North Ethiopia, 2019 (n=253).

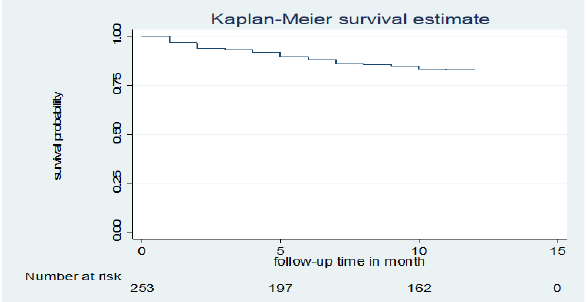

The Mortality Rate Among Children Co-Infected with TB and HIV

Of a total of 253 children co-infected with TB and HIV included in the study, 38 (15%) deaths and 215 (85%) censored were recorded. Of the censored cases, 186 (73.5%) were alive until the end of the follow-up period, 14 (5.5%) were transferred out, 15 (5.9%) were dropped out of follow-up, and the rest were in TB treatment. Those 253 TB and HIV co-infected children were followed for different periods (1 month to 12 months), which provides 226 child-month observations with a mean survival time of 10.75 (95% CI; 10.37 -11.14) months. In this study, the mortality rate was 0.17 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.23) per 1,000 child-month observations. The majority (73.7%) of the deaths occurred in the first six months of followup period and 15 (40%) occurred during the initial phase of TB treatment. All deaths 38 (15.02%) had occurred during ART. The cumulative probability of survival at the end of 2 months, 6 months, 9 months and 12 months was 94.0 %, 88.0%, 85.0 % and 82.9%, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival estimate of children co-infected with TB and HIV in general hospitals of two zones of the Tigray region, North Ethiopia, 2019.

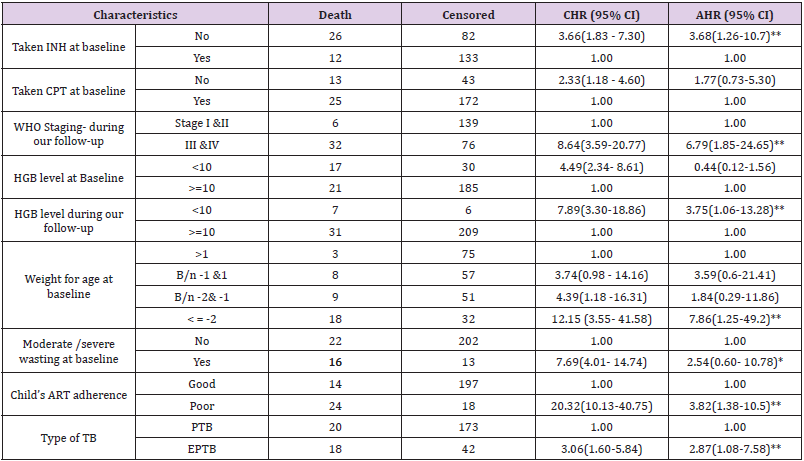

Predictors of Mortality Among Children Co-Infected with TB and HIV

Bivariate and multivariate analyzes were used to assess

the significant association between exposure variables and the

outcome variable. Underweight at baseline, moderate / severe

wasting at baseline, IPT, CPT, baseline hemoglobin level, level

of adherence to ART, type of tuberculosis, WHO staging during

follow-up, and hemoglobin level during follow-up were statistically

significant at 0.2 level of significance in bivariate analysis. In

multivariate analysis; underweight at baseline, IPT user/not/, ART

adherence level, type of TB, WHO staging during follow-up, and

hemoglobin level during follow-up were statistically significant at

0.05 significance level (Table 4).

The risk of death among children with TB and HIV co-infected

with underweight was approximately 8 times higher than children

with normal weight at baseline (AHR=7.9 (95% CI 1.26, 49.3)).

Children who did not take IPT were approximately 4 times more

likely to experience death than children who had taken IPT (AHR=3.69 (95% CI=1.26, 10.8)). The risk of child death with poor

adherence to ART was approximately 4 times higher than children

with good adherence to ART (AHR = 3.82 (95% CI: 1.38, 10.54)).

The risk of death among children infected with extrapulmonary

TB was also approximately 3 times higher than infected children

with pulmonary TB (AHR = 2.9 (95% CI: 1.1, 7.6)). During

follow-up, children with advanced WHO staging (III & IV) were

approximately 7 times higher risk of death than children with stage

I and II (AHR=6.79 (95% CI= 1.85, 24.9)). Anemic children were

approximately four times more likely to experience death compared

to nonanemic children during follow-up (AHR=3.76 (95% CI= 1.06,

13.27)).

Table 4: Results of the bivariate and multivariate analysis among children infected with TB and HIV in general hospitals of two zones of the Tigray region, North Ethiopia, 2019(n=253).

Discussion

The study provides information on the overwhelming problem

of high mortality and associated predictors among children with

TB and HIV coinfected. The mortality rate in this study was 0.17

(95% CI 0.12–0.23) per 1000 child-month observations. The result

was lower than the mortality rate reported from a single study

conducted in four developing countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia,

Cameroon and Vietnam), which is 0.370 per 1000 child- month

observations [23]. The difference may depend on the sample size

difference used by the studies.

In this study, mortality was higher in underweight children at

baseline. A similar finding was reported from a study conducted

in Thailand [24]. This might be the effect of underweight on

reducing body metabolic processes resulting in inadequate energy

acquisition that increases disease progression, which may end up

in death. Furthermore, inadequate weight gain in TB treatment

indicates a poor response to treatment [25]. However, stunting and

wasting were not significant in this study. This could be due to a

higher proportion (90%) of children diagnosed with malnutrition

in this study who received treatment for malnutrition. The study

also revealed that children who did not take IPT were three times

more likely to experience death than children who did take IPT.

This was in line with a study conducted in Gondar, Ethiopia [8].

The possible reason might be that IPT reduces the severity and

spread of TB disease. However, CPT was not found to be statistically

significant in this study, which was reported as a protective factor

for death in a study conducted in Gondar, Ethiopia [8]. This may

be because a higher proportion (78%) of our respondents had

taken CPT and were unable to make a difference. The number of

children who didn’t take CPT and died was too few (5.1%). For

better survival, HIV positive children should take both CPT and IPT

as preventive prophylaxis. In this study, the risk of death among

children infected with extrapulmonary TB was three times higher

than that of children infected with pulmonary TB. This result was

in line with a study conducted in Gondar, Ethiopia [8]. The reason might

be that the easy diagnostic technique for EPTB is not available

in most of our clinical settings, resulting in delayed initiation of

anti-TB treatment leading to rapid disease progression and easy

involvement of vital organs.

During follow-up, this study revealed that anemia was

associated with higher child death. No previous studies examined

anemia during follow-up, but at the beginning of the study, it was

identified as a predictor of mortality in studies conducted in Gondar

(Ethiopia) and Thailand [8-24]. Higher mortality with anemia may

be associated with decreased oxygen and nutrient care capacity of

the blood, resulting in inadequate oxygen and nutrient supply to

vital organs that become synergistic with TB and HIV [8]. In contrast

to other studies in Gondar (Ethiopia) [8], Thailand [24], Nigeria [6],

Malawi [26], and a single study in four developing countries [23];

WHO staging, CD4 count, and hemoglobin level at baseline were

not significantly associated with mortality in this study. The reason

might be that unlike these studies, our study assessed the effect of

the variables during follow-up time and at baseline. Most of these

variables were significantly associated during follow-up, which

shows a better effect on the outcome variable than at baseline.

This is one of the strengths of this study. Assessing the effect of

these variables during follow-up enables us to overlook the more

accurate effects of exposure variables on the outcome variable. The

study also considered the time of the event, which enables us to

consider the contribution of censored cases.

Limitation of the Study

Since the study was a retrospective review of the chart (secondary data), some variables not documented in the child’s medical records were missed. A further prospective study is needed to address other important issues not addressed by this study.

Conclusion

The mortality rate of children co-infected with TB and HIV in two zones of the Tigray region was high. Most deaths occurred within the first six months of the follow-up period. Underweight at baseline, IPT non-user, poor ART adherence, extrapulmonary TB, advanced WHO staging during follow-up, advanced/severe immunosuppression status during follow-up, and hemoglobin level < 10mg/dl during follow-up were predictors of increased mortality. This study is important for planning and decision making by pointing out gaps to make a successful strategy to combat TB and HIV and related consequences to increase the overall effectiveness of therapy in TB and HIV co-infected infected children.

For more

Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.