Abdominal Cystic Lymphangioma in Adults

Introduction

First described in 1913 by Koch, the cystic lymphangioma is a benign vascular tumor from lymphatics more common in children, suggesting a malformities origin [1]. The majority of cystic lymphangiomas occur at the cervico-axillary region. However, intra-abdominal locations such as the mesentery, retroperitoneum and epiploon are possible, but less common, representing about 5% of cases [2]. We report a case of mesenteric cystic lymphangioma extended to retroperitoneum with an emphasis on the role of imaging in leading to diagnosis.

Case Report

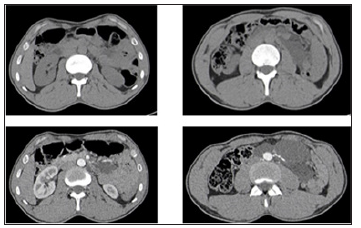

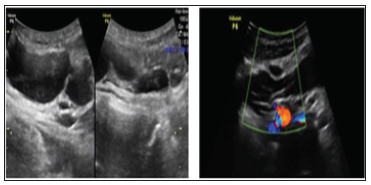

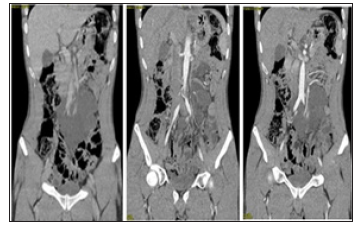

This is a 39-year-old patient, known to have an ectopic left testis, who suffered from a chronic abdominal pain with no general condition deterioration. With a normal clinical examination, abdominal ultrasound was performed showing a partitioned cystic mass of the left flank, with anechoic content, non-vascularized on color Doppler, extended to the pelvis (Figure 1). The inguino-scrotal ultrasound revealed an ectopic left testicle (inguinal) with a normal morphology. Abdominal CT was performed showing an extensive cystic mass along the mesentery, encompassing the divisional branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric vessels, the terminal portion of the abdominal aorta and the origin of its divi sional branches, which remain permeable, evoking a cystic lymphangioma. This mass had an intimate contact with the tail of the pancreas and the jejunum at the angle of Treitz (Figures 2 & 3). The surgical exploration found a pancreatic cystic mass extended to the mesentery and proximal jejunum and encompassing the mesenteric pedicle. As a result, the resection could not be complete leaving a residue near the mesenteric pedicle. In the anatomopathological analysis, the macroscopic and histological aspect was compatible with a cystic lymphangioma (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Axial abdominal CT with and without contrasting showing a cystic mass of the left flank encompassing some mesenteric vessels.

Discussion

The mesentery is a rare localization of cystic lymphangioma estimated at 1/100,000 in adults and 1/20,000 in children [3]. Pancreatic localization is even rarer. Its physio pathogenesis remains unclear, but can be explained by two theories:

Malformative Theory

In this case, the cystic lymphangioma arises from a disorder of embryogenesis due to a lack of connection between a group of lymphatic chains and the venous system leading to the isolation of lymphatic capillaries, their dilatation and then development of multiple cysts [3].

Acquired Theory

Especially in adults, cystic lymphangioma occurs in the aftermath of an obstruction of the lymphatic vessels related to a secondary cause (inflammation, trauma or degeneration) [3]. This theory is more and more abandoned [4]. According to the 2018 classification of vascular anomalies, the cystic lymphangioma is considered a lymphatic malformation (simple vascular malformation IIa) [5]. The abdominal cystic lymphangioma preferentially affects the mesentery and retroperitoneum, because of the richness of their lymphatic elements [6]. However, it can reach other intra-abdominal organs (spleen, pancreas, kidney, etc.) [4]. The nonspecific and polymorphic clinical presentation of cystic lymphangioma is related to the volume, the localization and the types of complications it can cause. It can be revealed by the palpation of an abdominal mass, by an abdominal pain, a fever, a hematemesis, a volvulus, etc. In our case, the patient suffered from a chronic abdominal pain. There is a particularly rare clinical form of an abdominal cystic dissemination mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis, called peritoneal cystic lymphangiomatosis [3].

The ultrasound appearance varies depending on the size of the cubicles. For macrocystic forms, it is a well-defined lesion, uni or multi-cell, with anechoic content separated by very fine fibrous septas. The content may be echoic in case of bleeding or infection. The arterial flow is poor with high resistivity indexes at the septas, without recordable flow within the cubicles. For the micro-cystic forms, the cubicles are very small (infra-millimetric), the mass appears pseudo-tissular, heterogeneously hyperechoic with a posterior reinforcement.

CT is an excellent complementary diagnostic tool. It shows a homogeneous hypodense (cystic) tumor, with thin walls, not enhanced by contrast. The density of the intra-cystic fluid can vary according to the contents which can be serous, chylous or hemorrhagic [3]. MRI is only used as a second-line exam, it allows a more precise study of the anatomical relationships with the neighboring structures.

According to Losanoff and Kjossev, a classification based on the morphotype of the lesion is retained to optimize the surgical approach [7]:

a) The “type 1” is pediculate with a risk of torsion, volvulus : The resection is easy.

b) The “type 2” is sessile, less mobile and may require sacrifice.

c) The “type 3” involves retroperitoneal extension (sometimes affecting vital structures), making total excision impossible. That was the case for our patient.

d) The “type 4” corresponds to an extensive lesion affecting multiple organs [7].

The differential diagnosis is made with all intra-abdominal cystic lesions:

a) Hydatid cyst

b) Cystadenoma / cystadenocarcinoma serous or mucinous mesentery

c) Mesenteric mesothelial cyst

d) Lymphocele

e) Dermoid cyst

f) Hemangioma

g) Hematoma

h) Appendicular mucocele

i) Ovarian cyst etc.,

The definitive diagnosis is made by histology [3]. In case of accidental discovery, therapeutic abstention with regular monitoring is recommended if the patient is asymptomatic. Spontaneous regression can be seen in 1.6 to 16% of cases. Regarding the high risk of progression (volume increase, appearance of complications), surgical excision is the classic approach. It must be total to avoid the recurrence (by laparotomy or laparoscopy) and the most conservative for the organs since it is a benign lesion [6]. The recurrence rate is estimated at 40% after incomplete resection and at 17% after macroscopically complete resection. Aspiration of the cyst content with or without sclerosant injection is a potential therapeutic alternative [6].

Conclusion

Abdominal cystic lymphangioma is a rare condition in adults. The clinical symptomatology is very variable. Imaging plays a key role in guiding the diagnostic, the preoperative assessment and the follow-up. The final diagnosis is made by histology.

Adequate Sleep at Night May Protect from Prostate Cancer-https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/2020/09/adequate-sleep-at-night-may-protect.html

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.