Caregiver Burden Among Informal Caregivers of Women with Breast Cancer

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer, and the leading cause of cancer death among women globally [1]. In 2018, there are over 2 million new breast cancer cases globally and 24.2% of all types of cancers; 54,900 new cases diagnosed in the United Kingdom (UK), 330,080 in the United State of America (USA), [2]. The incidence rate ranges from 29.3 per 100,000 people in North Africa to 22.4 per 100 000 in Sub-Saharan Africa [3,4]. The number of new cases and mortality rate from breast cancer is a result of population growth and increased life-span in both high- and low-income countries [5]. Before now, breast cancer is considered to be a disease of affluence that affects the developed countries but has now cut across all socioeconomic levels with burden more in developing countries such as Nigeria [6]. The increasing incidence of breast cancer in Nigeria and the paucity of the specialist man-power and structural facilities imply that the caregiving burden rests mostly on family caregivers/informal caregivers. Breast cancer presents a typical picture of the enormity of cancer burden on the Nigerian nation [7].

Breast cancer affects not just those who have the disease but also their informal caregivers who provide care. The informal caregivers perform many activities that used to be done in the health facilities by health workers [8]; they can help in drugs administration, counselling, dressing, and other treatment plans all through the different phases of managing the condition [9]. As most of them assume caregiving role without adequate training and are expected to meet up with caregiving demands without much help, they experience psychological worries, increasing rate of physiological illness, and social problems [10]. Studies in the developed countries had established that informal caregivers of patients with cancer are vulnerable to all kinds of psychological (e.g., anxiety, stress, depression) and physical (e.g., burn-out, increased mortality, loss of weight, poor immune functioning, and insomnia) burden [11,12]. However, little is known about problems facing the informal caregivers of patients with cancer in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Nigeria.

Study Aim

The study aimed to describe the impact of caregiving burden on the informal caregivers of women with breast cancer. The main objectives were to:

a) describe the level of the caregiver burden and characteristics of cancer patients and caregivers;

b) identify the factors related to the caregiver burden among the characteristics of patients and caregivers, caregivers’ resources, and self-efficacy; and

c) determine the relationship between the study variables (caregiver burden, social support, and self-efficacy).

The Conceptual Framework

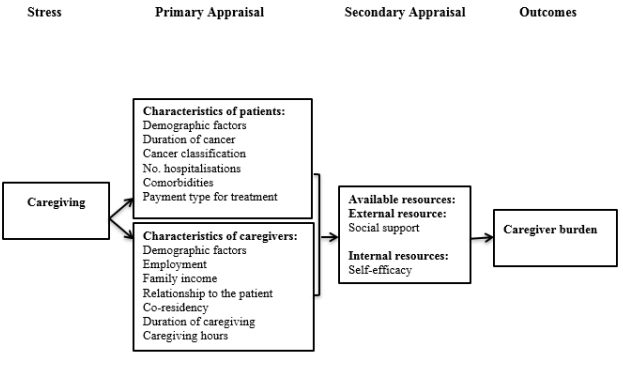

The conceptual model of this study is based on the work of Lazarus and Folkman (Figure 1), which suggests that an individual’s response to stress is affected by primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and available resources [13]. According to this model, primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and available resources interact and ultimately impact the individual’s stress response. The caregiver assesses the effects of various aspects of caregiving on himself/herself in the primary appraisal, which include potential factors of patients and caregivers. The patient factors include demographic factors; payment type for treatment; and disease characteristics. The caregivers’ characteristics include the demographic features of caregivers, employment status, and family income. The transaction between a person and his/her social or illness-related factors such as breast cancer can influence how individuals appraise and cope with the illness [14] (Figure 1).

Methods

Design

The study utilised a descriptive design. The total numbers of participants were 226 dyads attending the oncology clinic of the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital Zaria, Nigeria. The dyads were recruited through a convenience sampling technique after meeting the inclusion criteria for participation.

Participants

The dyads were recruited between March and September 2017. The inclusion criteria for patients were:

a) a primary diagnosis of breast cancer for at least six months; and

b) willing to participate in this study.

The inclusion criteria for caregivers were:

a) being the informal caregiver;

b) adults of age 18 years or above; and

c) living with the patients during caregiving.

Exclusion criteria were:

a) paid caregivers;

b) caregivers with severe functional or cognitive impairment; and

c) caregivers with comorbidities that involved a heavy burden, which increased their physical vulnerability

Measurements

Demographic Variables: The demographic data and clinical characteristics collected from the patients included the following: age, educational status, marital status, duration of breast cancer, breast cancer stage, number of hospitalizations in the past six months, number of comorbidities, and payment type for treatment. Caregivers’ demographic data include sex, age, marital status, educational level, number of caregiving hours (per day), relationship to the patient, duration of the caregiving, employment status, and family income per month.

Perceived Burden: ZBI, a 22 item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Each question is scored from 0 to 4, where zero = never, one = rarely, two = sometimes, three = quite frequently, and four = nearly always. The total ZBI was secured by adding all the scores for the 22 questions with a range of 0 to 88, higher scores suggesting higher burden [15]. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.99 in this study

Social Support: SSRS, a 10-item scale with three subscales (subjective support, objective support, and utilization of social support) was used, and higher scores indicate better support. The SSRS has adequate reliability and validity. The test–retest reliability coefficient was 0.92, and internal consistency of the scale was 0.89 [16]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.90 in this study.

Self-Efficacy: 10-item GSE was used. The GSE consists of a fourpoint scale, with a range from zero, indicating “completely wrong”, to four, indicating “totally right.” Higher scores indicate better selfefficacy. The GSE has adequate reliability and validity [17]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and test–retest reliability coefficient have been reported as 0.91 and 0.80, respectively, for chronic disease caregivers in China [18]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.86.

Data Collection

The informal caregivers who brought cancer patients to the oncology unit of the teaching hospital were interviewed. The purpose and process of the research were explained to them, they were asked to sign a written informed consent form. The instruments were explained to the participants, who then read through question items and ticked their answers on the space provided. The questionnaires took about 30 minutes to complete.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (ABUTH/EC/124/2017). Written consent was obtained from the participants and information was kept confidential. All participants were treated equally and impartially.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic characteristics and study variables. The independent samples t-test and analysis of variance were used to detect caregiver burden differences in subgroups of patients’ and caregivers’ characteristics. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to identify the factors contributing to the caregiver burden. The significant factors in univariate and correlation analyses were entered in a multivariate regression model, with the caregiver burden as the dependent variable. Significant demographic characteristics of the patients and caregivers, self-efficacy, and social support were the independent variables for analysis. All tests were two tailed, and P<0.05 was considered the statistical significance level.

Results

Among the 244 potential eligible participants we contacted, five patients refused to participate due to physical reasons, nine caregivers declined due to insufficient time, and four caregivers did not provide a reason. A total of 226 participants (patient–caregiver dyads) completed the survey and were included in the analysis.

Patient’s Characteristics

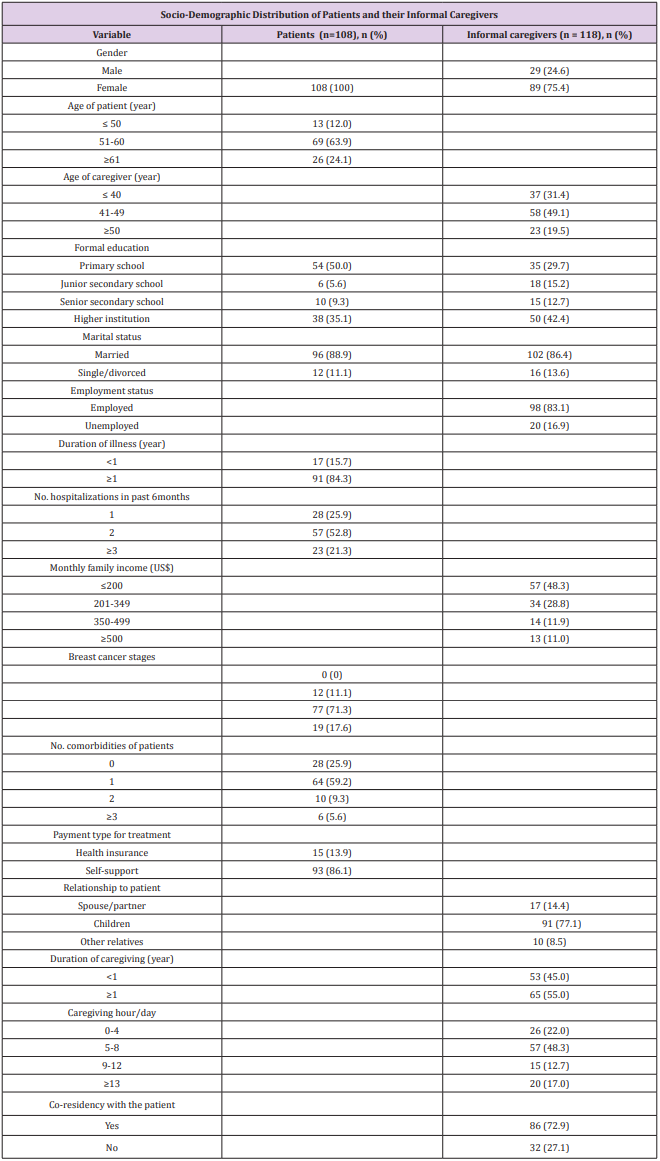

Among the 108 patients, the average age was 59.7 years (standard deviation [SD] = 14.9), and 96 patients (88.9%) were married. More than half of participants (55.6%) had less than secondary school education. The majority (86.1%) pay for the medical bills. The cancer stage distribution among patients ranged from stage II to stage IV; there were 12 stage II patients (11.1%), 77 stage III patients (71.3%), and 19 stage IV patients (17.6%). The overall mean score on the cancer stage was 3.21 (SD= 0.57). More than half (52.8%) had two hospitalization experiences within the past 6 months. The majority of patients (74.1%) had at least one comorbidity (Table 1).

Caregiver’s Characteristics

The average age of the informal caregivers was 41.9 years (13.8), and the age range was 18– 65 years. Most of the caregivers were female (75.4%) and married (86.4%). The majority of caregivers (87.3%) had an educational level of junior secondary school or above. The majority (89%) had a monthly family income of less than US $500, which is a low-income level. Most of the caregivers (83.1%) had a full-time or part-time job. The majority of caregivers (77.1%) were adult children of the patients, and (14.4%) were the spouses/partners. Most caregivers (78%) spent more than 4 hours per day providing care for the patients, and 55% had cared for the patients for more than one year. The majority of caregivers (72.9%) lived with the patients (Table 1).

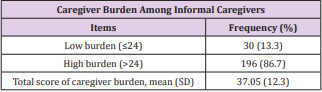

Caregiver Burden Among Informal Caregivers

The mean ZBI score was 37.1 (12.3). 13.3% had “low” care burden and 86.7% had “high” care burden (Table 2).

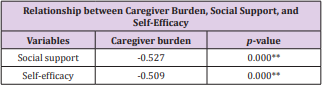

Relationship between the Caregiver Burden, Social Support and Self-Efficacy

The Pearson correlation analysis showed that the caregiver burden was inversely associated with social support (r= -0.527, p<0.01) and self-efficacy (r= -0.509, p<0.01) (Tables 2 & 3).

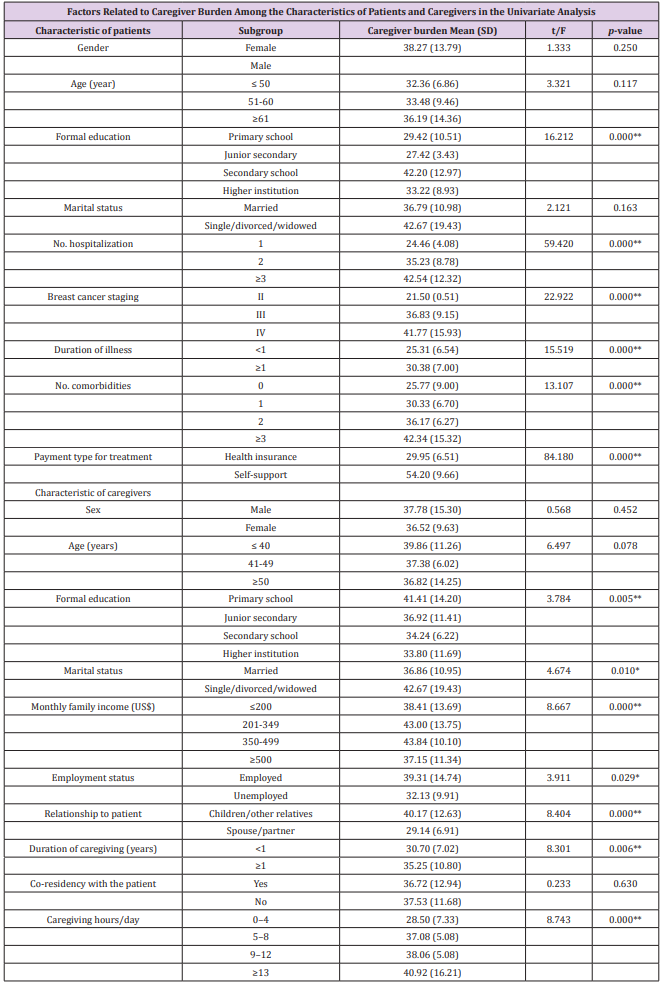

Table 3: Socio-demographic distribution of patients and their informal caregivers.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Factors Related to Caregiver Burden

The univariate factor analysis showed that there were significant relationships between the caregiver burden and patient characteristics, including educational status, number of hospitalizations in the past six months, breast cancer staging, duration of illness, number of comorbidities, and payment type for treatment. In addition, patients with a lower education level, more hospitalization experiences, a higher breast cancer staging, longer duration of illness, more comorbidities, and self-support for treatment demonstrated a higher caregiver burden (Table 4). The univariate factor analysis revealed that there were significant relationships between the caregiver burden and characteristics of caregivers (educational level, marital status, monthly family income, employment status, relationship to the patient, duration of caregiving, and number of caregiving hours per day). In addition, caregivers with a lower educational level, lower monthly income, longer duration of caregiving, more caregiving hours per day, as well as adult-child caregivers also suffered higher level of caregiver burden (Table 4). Multivariate analysis was used to detect factors associated with the caregiver burden, using the caregiver burden as the dependent variable and significant variables from the univariate and correlation analysis as independent variables. The multivariate analysis showed that the payment type for treatment (b = -0.431, p<0.01), monthly family income (b = -0.133, p<0.01), relationship to the patient (b = 0.404, p<0.01), self-efficacy (b= -0.314, p<0.01), and social support (b = -0.137, p<0.01) were significantly related to the caregiver burden. 44% of the variance in the caregiver burden was explained by the identified significant factors (Table 5). The statistical power of this study was 82.7%, which was adequate to explain the caregiver burden (Tables 4 & 5).

Table 4: Socio-demographic distribution of patients and their informal caregivers.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. Statistic from a t-test analysis, F statistic from an analysis of variance.

Table 5: Socio-demographic distribution of patients and their informal caregivers.

**P<0.01. Standardized coefficient. Adjusted R2 = 0.43.7, P<0.01.

Discussion

This study revealed that the majority of informal caregivers (86.7%) had a high level of caregiver burden. The score of caregiver burden in this study was higher than the results of other studies on cancer caregivers. The factors associated with caregiver burden were payment type for treatment, monthly family income, relationship to the patient, social support, and caregiver’s selfefficacy. In this study, most caregivers were in their early 40s, and the majority of caregivers were children of women with breast cancer. Our finding supports similar prior study, which reported that most family caregivers were sons and daughters of the patients with average age of 42 [19]. The results could be related to the cultural norms of Nigeria. The cultural teachings uphold the family first and dictate that children will take care of their aged parents [20]. It is considered a basic moral obligation, rather than a virtue, for adult children to take care of their ill and aged parents in this context [21]. The adult children might be considered as an unfilial piety and despised by the public if they do not care for their parents. As a result, most adult children live with their aged parents and take care of them, which may be different from the culture of Western countries. Strategies specific to the younger caregivers should be taken to reduce their caregiver burden, as discussed later.

The caregiver burden of informal caregivers of women with breast cancer in this study was 37.1 + 12.3, which is lower than that reported among caregivers of dementia patients [22], indicating that different diseases have different levels of caregiver burden. However, the burden reported in this study was higher than the figures reported among caregivers of cancer patients in Southern Nigeria [23]. The different level of local socio-economy might account for the results, because this study was conducted in Northern Nigeria, a less developed area in socio-economic with fewer medical resources compared to southern area. The majority of caregivers (83.7%) in this study had a monthly family income of less than US $500. As a result, the heavy financial burden might increase the caregiver burden. Proposed strategies to relieve the caregiver burdens in low-income countries include adding government financial support, expanding the coverage of health insurance, and providing more resources. We found that caregivers who were adult children expressed the highest level of burden among all informal caregivers. Findings from prior studies in this area were inconsistent [9,24,25]. Some studies were in agreement with our results [9,25], but others reported that spousal caregivers suffered the most [24].

Adult children are more likely to suffer a higher caregiver burden due to conflicts between their caregiving tasks, careers, and nuclear families [25]. In this study, most caregivers were adult children who were employed. Employment outside the home was associated with an additional burden because of conflicts between working and caregiving tasks [26]. In contrast, most of the spouses of the cancer patients had retired, according to the Nigerian retirement age (60 year of age, or 35 year in service), and they had more spare time and energy to take care of the patients, which might decrease the burden. Moreover, the one- child belief and traditional care for their sick and aging parents. As a result, most adult children live with and take care of their parents and parents in- law. In these circumstances, adult children have an additional burden with the obligation of taking care of four elderly parents, particularly those with a low family income. This finding provides an incentive for the Nigerian Government and medical staff to pay more attention and provide additional support for adult-child caregivers. Taking into consideration the younger age of most caregivers, it is important to establish day care respite services.

Technological resources adapted to the caregiver’s schedule are useful for these younger caregivers, including a telephone-based follow up, online caregiver guidance, and Internet support groups. Consistent with the results of other studies, social support had an inverse relationship with caregiver burden [27,28]. Caregivers with more social support from their families and professional institutes might have more time or energy to care for themselves and patients, as well as handle family and social activities. Additionally, social support from families made it easier for caregivers to adapt their lifestyles to their patients’ situations, minimizing caregiver burden [29]. Currently, due to insufficient medical resources in Nigeria, the major support for caregivers is from family members, and it specifically consists of emotional support. As a result, more social support from medical staff is needed to reduce the caregiver burden, such as providing professional information and support for informal caregivers in the community, strengthening home-care services, and providing support groups for caregivers. Consistent with other studies, we found that self-efficacy was associated with a reduced caregiver burden [30,31].

Caregivers with high self-efficacy tended to be able to deal more readily with caregiving stress and tasks. Therefore, strategies to improve self-efficacy, such as additional training, follow up, peer education, and support groups for caregivers might decrease the caregiver burden. The longer time spent in caring for patients per day were associated with higher burden. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study [32] where disrupted schedules in daily activities were related to caregiver burden. The payment type for treatments and monthly family income were also associated with the caregiver burden. Caregivers who took care of patients with health insurance expressed a lower caregiver burden compared to caregivers who were self-paying. These results were consistent with other studies reporting that low economic status was linked to an increased caregiver burden [26,33]. As a result, more financial and policy support are necessary for caregivers with a low income and those caring for patients with self-payment.

Implications for Practice

The results of this study inform strategies and interventions that are suitable for low-income community. Assessment for breast cancer caregiver burden is needed to identify high-risk caregivers. Early interventions to increase the social support and self-efficacy for caregivers are necessary. Examples include governmentsponsored health policies and services, such as enlarging the coverage of health insurance and offering respite care service. Moreover, targeted instructional support that integrates knowledge, skills, and coping strategies is essential for breast cancer caregivers to reduce their burden.

Limitations

Limitations to the study are the descriptive design and convenience sample, making it difficult to identify causal relationships. As a result, a longitudinal study is recommended. A large, multi-site study is needed. Other potential variables, such as the coping style, family function, and health status of caregivers, should be considered in future studies.

Highlights

In this study, majority of informal caregivers of women with breast cancer had a high level of caregiver burden. The factors associated with caregiver burden were payment type for treatment, monthly family income, relationship to the patient, social support, and caregiver’s self-efficacy. Social support and self-efficacy had an inverse relationship with caregiver burden. Caregivers with more social support from their families and professional institutes might have more time or energy to care for themselves and patients, as well as handle family and social activities. Caregivers with high self-efficacy tended to be able to deal more readily with caregiving stress and tasks. In a country such as Nigeria, more attention should be placed on financial burden and insufficient resources associated with the caregiver burden.

Conclusion

The financial burden and insufficient resources are factors associated with the caregiver burden among caregivers in lowincome countries. More attention and support should be placed on adult-child caregivers in low-income countries. Assessments of the caregiver burden and targeted interventions, such as increasing self-efficacy and social support in low-income areas, are necessary to identify and alleviate the caregiver burden.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the support received from the management of ABUTH and the research assistants.

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.