Effects of 12-Week Cognitive and Exercise Interventions on Physical, Cognitive Function and Health-Related QOL in Elders With MCI

Introduction

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is an intermediate state between the cognitive changes of normal aging and dementia. Seniors with MCI are at the high-risk group for progressing dementia-a rate of 10 to 15 % per year compared with 1% to 2 % per year among the general population [1,2]. Given that this cohort is at high risk of developing dementia and lowering quality of life, it is important to identify effective intervention and appropriate place for them to perform the intervention to manage the cognitive decline and maintain the quality of life in the community level. In the Fratiglioni et al. [3] (2004)’s general model of dementia occurrence, the occurrence of dementia considers the effect of different risk and protective factors acting at different times during the life course of an individual. After 60’s, the protective factors for dementia include vibrant social network, mental activities, and physical activity.

Evidence suggests that cognitive function in older adults may be affected by the social network including social integration [4] and social support [3,5,6]. Some studies have indicated that people who experience more significant levels of social interaction and support have better mental health outcomes [7,8]. Further, there is more evidence of the effects of leisure activities on health and survival, especially physical activities and physical exercises [9]. Physical activity as the non-pharmacological treatment for MCI and dementia have received considerable attention. Evidence shows that estimated 17.7% of Alzheimer disease cases could be prevented through physical activity [10] and the Higher one physically active, the lower the incidence of MCI and dementia [1,11].

Community senior centre offers a wider variety of programs and services including meals, nutrition program, information and assistance, fitness and wellness program. Evidence suggests that cognitive function in older adults may be affected by modifiable risk and protective factors including smoking, poor diet, level of physical activity, cognitive stimulation and social relationship [3,6,7]. However, A few studies reported the effect of the combination of physical, cognitive intervention and social network. Further, the role of community senior centre as a hub of prevention of dementia has not been investigated. The local community senior centre must be a good place to prevent elderly from dementia by providing wellstructured cognitive program, physical activity, and social network. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of a structured cognitive, physical activity and social network on physical and cognitive function, depression, QOL in MCI and normal cognitive elders.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Pre-post design with subgroup analyses was conducted to compare elders with normal to with MCI. Subjects were recruited from 30 local community senior centres. Individuals were considered eligible if they

a) Were at least 65 years old;

b) Were able to participate senior centre program;

c) Were able to communicate;

d) Were able to maintain ADL or slight impairment IADL, and

e) Complete written consent form.

Procedures

Participants were assessed by the EQ-5D (EuroQOL five dimension) [12] questionnaire, self-rated health, MMSE-K, Geriatric Depression Scale short form in Korean version (GDS-SFK), and 2-minute step test. EQ-5D consists of five dimensions including self-care, mobility, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/ depression, each of which offered three possible responses: no problems/ some or moderate problems/ extreme problems (EQ5D, 2016). The answers to each EQ-5D dimensions were collapsed into a two-tier variable: In each EQ-5D dimension, “no problem” was considered as normal, whereas “some problems” or “severe problems” were considered problematic. Self-rated health was assessed by asking “would you say your general health now is excellent, good, fair or poor” and coded it as that excellent = 1 and poor = 4. Cognitive function was measured with Mini-Mental State Examination-Korean version [13]. Depression was measured with Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) short form and categorized.

The Geriatric Depression Scale-Short form in Korean version (GDS-SFK) [14] was used to index depressive symptoms. The GDS-SF K included 15 items with yes/no format. Five positive items (e.g., “Are you satisfied with your life?”_ and ten negative items (e.g., “Do you feel that your life is empty?”. The total score was calculated counting the number of responses that suggest probable depression. The 2-minute step test is a measure of aerobic endurance. It is the number of times in 2 minutes that a person can step in place, raising the knees to a height halfway between the patella and iliac crest [15].

Intervention

The multicomponent intervention consists of physical activity, cognitive training, nutrition education and social activity. Physical activity was based on ‘15-minute plus’ exercise manual [16,17]. The intervention is held in the group format; each group has 8-25 participants. The intervention is held in once a week, 120 minutes per session for 12 weeks.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the distribution of age, sex, BMI, MMSE and EQ-5D dimension. Chi-square and independent sample t-test were conducted to conducted to compare the baseline data between normal and MCI group. Prepost-test comparison was made by paired sample t-test. 2x2 repeated measure ANCOVA was conducted to see differences between time x group interaction. IBM SPSS statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all the analyses. Values p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

General Characteristics of Study Population

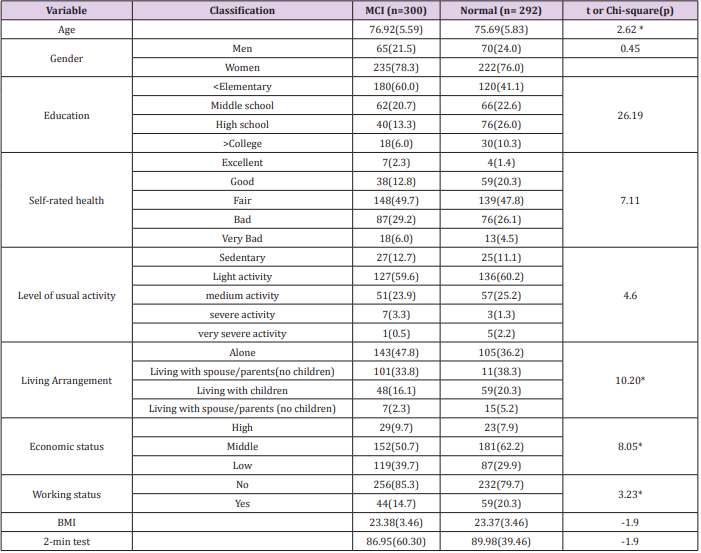

The general characteristics of participants were shown in Table 1. The study population included 300 MCI and 292 normal cognitive elders. The average age of study population was 77.32 years (SD: 5.39, ranging: 65-93). The mean age of normal and MCI was 76.92 and 75.69years, respectively. There was a significant difference in mean age (t=2.62, p<0.05), living arrangement (F= 10.20, p<.05), economic status (F=8.05, p<.05) and working status (F=3.23, p<.05) between MCI and normal group. Elders with MCI were more likely than normal elders to live alone (p<.05), have lower economic status (p<.05) and less work (p<.05).

Intervention Effects

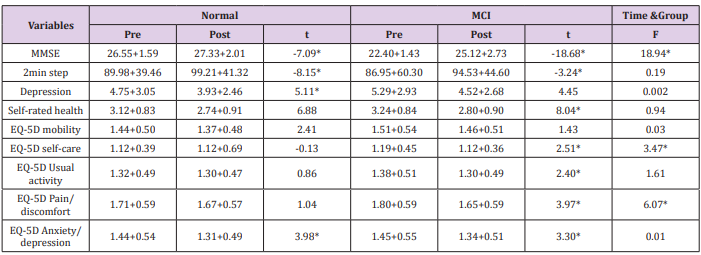

The effects of the intervention were shown in Table 2. After 12 weeks of intervention, in normal group, variables were significantly improved: MMSE (t=-7.09, p<.05), 2-min step (t=-8.15, p<.05), Depression (t=5.11, p<.05), EQ5D Anxiety/depression (t=3.98, p<.05). In addition, similar with normal group, variables in MCI group were significantly improved as well: MMSE (t=18.68, p<.05), 2-min step (t=3.24, p<.05), all EQ5D subdivision except mobility (p<.05). Further, there was a significant difference between the normal subjects and MCI in MMSE (F=18.94, p<.05), EQ-5D selfcare (F=3.47, p<.05), EQ-5D Pain/discomfort (F=6.07, p<.05).

Table 2: Effects of 12-week combined cognitive and exercise interventions on physical, cognitive function and health-related QOL.

Note: F: ANCOVA controlling for age, economic status, living arrangement, working status; * p<.05.

Discussion

In this study, we described the effects of combined cognitive and exercise interventions for people with cognitive impairment and cognitively healthy elderly in the community-based senior centre settings. In the results, we found that MCI patients in the intervention group demonstrated greater post-program improvement in cognitive function than cognitively normal elderly in community integration. Further, MCI patients showed greater post-program improvements in health-related QOL, especially selfcare and pain.

These results were like previous research by Ding et al. [18] and Li et al. [19]. Ding et al. [18] show MCI patients had the significant improvement in EQ5D pain compared with that of normal cognitive elders. Further, patients with MCI improved significantly overall cognition by cognitive intervention such as MMSE, self-rated memory problem, ADL, QOL [19].

Individuals with MCI demonstrate impaired performance in daily activities. People with cognitive impairment need to sustain their cognitive capacities and their abilities to perform activities of daily living as high a level as possible. Therefore, developing an intervention that is designed to maintain independence and stimulus cognitive function for individuals at risk for dementia is critical. The results of this study show us that progression to dementia may be slowed by the potential intervention that is designed to slow decline in disability for individuals at risk for dementia due to MCI. Further, this study provides information about the feasibility of community senior centre conducting a potential intervention for people with MCI. The feasibility of the project includes recruitment, the ability of this population to undertake and remain safely engage in the intervention and the sustainability and responsiveness of the outcomes. Progression to dementia may be slowed due to the link between engagement in normal cognitive elders with various activities stimulating cognitive as well as physical function. In this study, senior centre seems the good place where to give people with MCI and their family members an opportunity to interact with other seniors and develop meaningful social connection between the cognitive normal senior members that would reach across the barriers of age, disabilities, and abilities. Increasing meaningful social involvement in senior centre enhance potentially neurocognitive and emotional health. Individuals with MCI retain the capacity to problem solve and develop effective strategies to manage daily activities.

Thus, an intervention held with cognitive normal elder, which help individuals with MCI develop effective strategies in the course of daily activities may delay disability and may slow progression to dementia. Senior cantered multi-component intervention may have lower direct and indirect medical costs by fewer hospital and physician visits, and formal and informal caregivers service. Making a senior centre more dementia friendly place through participation is another challenge. The mechanisms of action should be further explored as a potential intervention to slow the decline in daily activities for individual with MCI. Findings from this study are informative but should be interpreted with caution. This study lacks a randomized trial, which decreased the methodological rigor.

However, these findings suggest factors that should be considered in future studies that examine non-pharmacological intervention for individual with MCI. Despite this limitation, the results of this study is meaning by demonstrating that the findings could be replicated in the similar setting. Further, this study provides the effectiveness of multi-component intervention and evidence of mixing people with MCI with normal cognitive elders in the community senior centre. Therefore, this study adds to the knowledge base about approaches for building dementia friendly communities and reducing dementia stigma.

ConclusionA twelve-week combined physical and cognitive intervention

improve both physical function, cognitive function and HRQOL

among both cognitive normal and MCI elders and imparted

cognitive benefits in seniors with MCI.

More BJSTR Articles: https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.