Deficit Syndrome of Schizophrenia: Assuaging by Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor

Introduction

Schizophrenia is often described in terms of positive and negative (or deficit) symptoms [1]. Positive symptoms are those that most individuals do not normally experience but are present in people with schizophrenia. They can include delusions, disordered thoughts and speech, and tactile, auditory, visual, olfactory and gustatory hallucinations, typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis [2]. Positive symptoms generally respond well to medication [3]. Negative symptoms are deficits of normal emotional responses or of other thought processes and are less responsive to medication [3]. They commonly include flat expressions or little emotion, poverty of speech, pleasure, lack, and lack of motivation. Negative symptoms appear to contribute more to poor quality of life, functional ability, and the burden on others than do positive symptoms [2]. People with greater negative symptoms often have a history of poor adjustment before the onset of illness, and response to medication is often limited [3]. So, among the constellation of symptoms that characterize schizophrenia, negative symptoms have emerged as a critical feature linked to the functional impairment experienced by affected individuals [1]. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia represent deficiencies in emotional responsiveness, motivation, socialization, speech and movement.

When persistent, they are held to account for much of the poor functional outcomes associated with schizophrenia. There are currently no approved pharmacological treatments. While the available evidence suggests that a combination of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication may be effective in treating negative symptoms, it is too limited to allow any firm conclusions [2]. Hence, the past decade has witnessed a resurgence of interest in the development of novel pharmacological agents to treat the negative symptoms of schizophrenia [3]. Antidepressants have plenty and varied credentials as plausible therapeutic agents regarding negative symptoms of schizophrenia [1-3]. Most of the trials of antidepressants in schizophrenia are add-on studies and placebocontrolled trials of antidepressants in non-depressed schizophrenic patients have not shown consistent results [4]. For example, whilst fluvoxamine and fluoxetine have shown efficacy over placebo in some trials [5,6] on the contrary, there are similar trials as well with citalopram and fluoxetine with negative outcome that make crucial judgment more complicated [7,8].

As another example, while a trial of amitriptyline in this regard showed positive results [9], but no significant effect with maprotiline in comparable assessment were visible [10]. Antidepressants like mirtazapine and mianserin as well have been studied with encouraging results [11-13]. Reboxetine [2-[(2-ethoxyphenoxy)-phenyl-methyl]morpholine] is an antidepressant drug used in the treatment of clinical depression, panic disorder and ADD/ ADHD and exists as two enantiomers, (R,R)-(-)- and (S,S)-(+)-reboxetine[14]. Both the (R, R)-(-) and (S,S)-(+)-enantiomers of reboxetine are predominantly metabolized by the CYP3A4 isoenzyme [15]. Reboxetine essentially acts as a pure norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI) with very little activity on the serotonin transporter and without direct effects on the dopaminergic neurotransmission [16] and hence is a somewhat well-tolerated, fairly selective “noradrenergic” agent. NARIs may be especially useful in drive-deficient “anergic” states where the capacity for sustained motivation is lacking and also in the treatment of retarded and melancholic depressive states with a reduced capability to deal with stress [17]. Previous studies have shown contradictory results [18,19] concerning the helpful effects of reboxetine on deficit symptoms. Objective of this study includes exploration of the effectiveness of reboxetine, as an adjunctive treatment, in a group of schizophrenic inpatients with prominent negative symptoms.

Method

50 male inpatients meeting diagnosis of schizophrenia, according to the clinical interview and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (Code: 295.xx) [20] were entered, into a 12-week parallel group, double-blind study for random assignment to adjunctive reboxetine(n=25 patients) or placebo(n=25 patients). Since the field of research was restricted to chronic male district of the psychiatric hospital therefore all of the samples were selected among chronic male schizophrenic patients. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written Informed consent was obtained from either the participant or a legal guardian or representative. In addition, whole of the procedure was approved by the related ethical committee of the university. The inclusion criteria, in addition to the diagnosis of Schizophrenia, included the existence of apparent negative symptoms and duration of at least two years. Cases with Co-morbidities like Major Depressive Disorder, mental retardation, neurological disorders, medical complications, severe aggressiveness, medical deafness or muteness, were excluded from the study. In addition, cases with diagnosis of Schizoaffective Disorder or cases that were prescribed atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants or lithium as well had been expelled. High negative symptoms scores (more than 20% of total SANS, =or>24), low positive symptoms scores (less than 20% of total SAPS, =or<35), low extra-pyramidal symptoms scores (less than %25 of total SAS, =or<10), and finally low depressive symptoms scores (HDS less than 10) were at the base of our inclusion criteria. To exclude depression and cognitive disturbances that could be confused with negative symptoms, Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS) and Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) were used respectively.

Evaluator [a psychiatrist] as well remained unaware concerning the abovementioned panel and the type of medications prescribed for each group. All The patients remained hospitalized throughout the experiment. Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) was used as the primary outcome measure in this experiment for appraisal of Affective blunting (restricted emotional expression), Alogia (reduced spontaneous speaking), Avolition (lack of drives, Anhedonia (lack of sense of pleasure) and Attention deficit [17]. In addition, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS), Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS) and Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS) were used for comparison of the intervening parameters in this study. Duration of assessments was twelve weeks, and the patients were assessed at the beginning, as baseline, and at the end of the 4th, 8th and 12th week with regard to SANS and SAPS. All of the remaining scales had been scored at the initiation and conclusion of the experiment. Analysis of the Scores of SANS at 12th week was the core objective of this study. It is mentionable that according to a Priori Power Analysis and based on a large effect size (according to Cohen’s definition) along with an alpha=0.05; a total sample size of at least 42 (2 x 21) could predict a power=%80 in this regard [Critical t (40) =1.68, delta=2.59, actual power=0.81].Given the high probability of dropouts, we increased the sample size to 2 x 25.

Statistical Analysis

Samples had been compared on baseline characteristics using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continues variables in order to assess the efficacy of the randomization procedure in ensuring homogeneity between the two treatment groups. The primary analysis was carried out according to the intention-to-treat, last- observation –carried-forward (LOCF) approach. Treatment efficacy was analyzed by t test, Split-plot (Mixed) and repeated –measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing both groups over 12 weeks, with regard to SANS and SAPS. Cohen effect size estimates were used when comparing baseline to end-point changes in SANS. All tests of hypotheses were tested at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. Response was defined as a reduction of 20% or more in the severity of SANS’s score (total and/or sub-scales).

Results

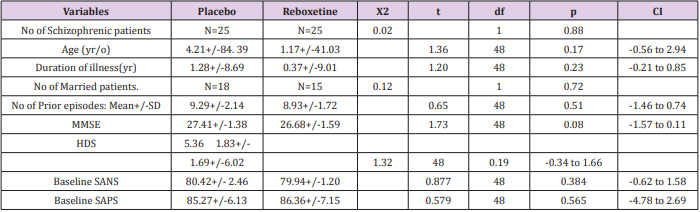

Analysis for efficacy was based on data from equal number of patients (n=25) in both groups, because there was no drop out throughout the assessment. It is mentionable that since all of the patients were hospitalized all over the study in the hospital and furthermore due to lack of serious adverse effects in them and besides short duration of experiment, hence there was no premature discontinuation in none of the aforesaid groups. Groups were originally analogous with respect to comparable demographic and diagnostic variables (Table1). The main outcome measures in this assessment were mean total changes of SANS and though at baseline there was no important difference regarding them between experiment and control groups, but at the end reboxetine illustrated significant improvements in the severity of negative symptoms (Tables 2 & 3). Regarding to baseline and final mean total scores of SAPS, SAS and HDS also no significant difference was observable among them (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

Abbreviations: MMSE: Mini-Mental Status Examination; HDS: Hamilton Depression Scale; SANS: Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS: Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms

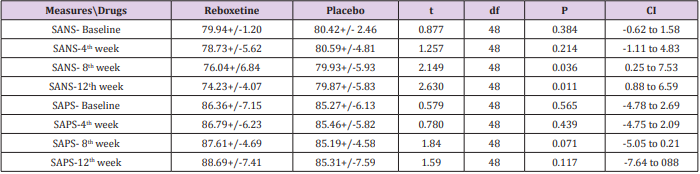

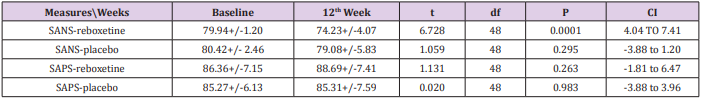

Table 2: Between-group analysis of primary outcome measures at baseline, 4th, 8th and 12th week.

Abbreviations: SANS: Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS: Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms

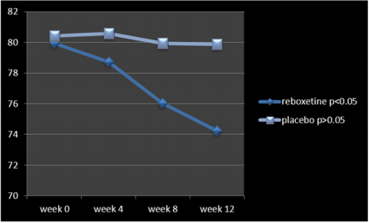

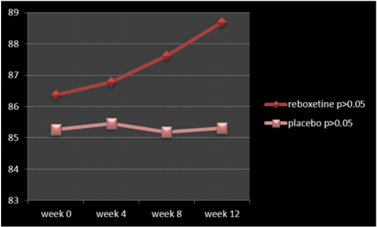

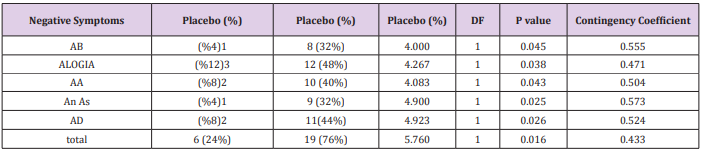

According to the findings and at the end of the assessment,76% of patients in the reboxetine group, comparing to 24% of them in the control group, based on improvement in SANS scores, demonstrated some positive response to this adjunctive augmentation , (x2 =5.760, DF=1,P=0.016) (Table 4) (Figure 1). In this regard, the SANS’s mean total score in the reboxetine group decreased from 79.94+/-1.20 to 74.23+/-4.07 (95%CI: 4.04 to 7.41, DF=48, t=6.728, P<0.0001) at the end of the study, while such an improvement was not manifest in the placebo group (80.42+/- 2.46to 79.08+/-5.83; 95%CI: -3.88 to 1.20, df=48, t=1.059, P=0.295) (Table3). Between-group analysis showed that the mean total scores of SANS in the reboxetine group, in comparison with the control group, improved significantly at 8th and 12th week (P<0.036 and P<0.011 respectively) (Table 2). Repeated-measures (within-subjects factor) analysis of variance (ANOVA), regarding the mean total scores of SANS, showed significant improvement in the reboxetine group [F (3, 72) = 3.25 p<0.026579 SS=591.95 MSe=60.66], along with non-significant change in the control group (F (3, 72) = 0.231 p<0.874429 SS=35.74 MSe=51.54). Split-plot (Mixed, Between-within) design ANOVA also showed considerable difference in this regard among them [F (3, 96) = 4.11 p<0.0019768 SS=6.71 MSe=32.98]. Also regarding the mean total scores of SAPS, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) illustrated non-significant alterations in the reboxetine and control groups [F(3,72) = 0.853 p<0.469600 SS=76.85 MSe=30.04 and F(3,72) = 0.009 p<0.998834 SS=0.83 MSe=31.00 respectively] and likewise Split-plot (Mixed) design ANOVA did not prove any considerable difference in this regard among them [F(3,96) = 0.397 p<0.755679 SS=35.56 MSe=29.88] (Figure 2).

Table 3: Intra-group analysis of primary outcome measures between baseline and week 12.

Abbreviations: SANS: Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS=Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms

Table 4: Number of responders with significant improvement in total and subtests of SANS.

Abbreviations: AB: Affecting Blunting; AA: Avolition-Apathy; An As: Anhedonia-Asociality; AD: Attention Deficit

According to the results, all of the subscales of SANS demonstrated significant improvement in the reboxetine group visà-vis the placebo group (Table 4). Albeit no important altering in the positive, extra-pyramidal and depressive symptoms all through the present study was discernible, but it should be pointed out that nevertheless by means of this minor dosage of reboxetine the mean total scores of SAPS showed a trivial escalation in the experiment group (86.36+/-7.15to 88.69+/-7.41, 95%CI: -1.81 to 6.47, DF=48 t=1.131, P=0.263). 48% (n=12) of the patients in the placebo group and 40% (n=10) of them in the reboxetine group required anticholinergic drug for remission of the tremor or Parkinsonism at some stage in the study (Chi-Square=0.081, DF=1, P=0.77). Since the sample size was small, hence the Effect size (ES) was analyzed for change on the SANS at the end of treatment, which indicated a large (“ d = or >0 .8”), readily observable improvement with reboxetine (Cohen’s d = 2.91, effect-size r = 0.82). Nine patients in the reboxetine group (36%) experienced some mild to moderate side effects such as headache, insomnia, constipation and dry mouth but neither of them led to any major problem or withdrawal from the experiment.

Discussion

The management of negative symptoms appears to be a major challenge because of functional disability induced by these symptoms and their relative resistance to treatments currently on the market 1. Treating negative symptoms of schizophrenia is a major issue and a challenge for the functional and social prognosis of the disease, to which they are closely linked. First- and second-generation antipsychotics allow a reduction of all negative symptoms. The hope of acting directly on primary negative symptoms with any antipsychotic is not supported by the literature. However, the effectiveness of first- and second-generation antipsychotics is demonstrated on secondary negative symptoms [2]. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are debilitating, and they contribute to poor outcome in schizophrenia. Initial enthusiasm that second-generation antipsychotics would prove to be powerful agents to improve negative symptoms has given way to relative pessimism that the effects of current pharmacological treatments are at best modest [3]. According to the assessments, reboxetine, as an adjuvant agent, induced notable improvement in the negative symptoms, while in the meantime it caused not important increase in the positive symptoms.

As is known, reboxetin is helpful in treatment of depression [21]. It also reduces olanzapine-associated weight-gain through activation of the adrenergic system [22]. As is known, the dopamine-blocking properties of antipsychotic drugs may have a negative effect on mood and drive and, in addition, treatment with typical antipsychotics has been associated with emergence of depression in schizophrenia [23]. There is evidence that NARIs indirectly enhance central serotonin function by a mechanism that doesn’t depend on reuptake inhibition. An association between negative symptoms and dysregulation of the serotonin system is suggested by an abnormal prolactin response to fenfluramine in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder [24]. On the other hand, reboxetine also has a modulating effect on the dopaminergic cells in the ventral tegmental area and may cause a selective increase in the dopamine availability in the prefrontal cortex [25]. Thus, it may possibly help to undo a number of challenging side effects of antipsychotics on mood and drive. In a comparative study, reboxetine was considerably better than paroxetine and placebo regarding improvement of attention and enhancement of cognitive functioning in patients suffering from MDD [26]; an outcome that persuades comparable survey respecting schizophrenic patients.

In a six-week randomized controlled trial on 30 schizophrenic patients, there was no significant difference among reboxetine and placebo on the topic of improvement of deficit symptoms [18]. Conversely, in an open-label trial for seeking the effectiveness and tolerability of the adjunctive reboxetine in a group of schizophrenic patients with prominent depressive or negative symptoms, all clinical scores improved significantly as a result of adjunctive treatment with reboxetine [19]. In addition, all of the patients tolerated treatment without any major adverse effects. The results of the present study are in agreement with the later study. Also, the short period of this assessment and lesser dosage of reboxetine prescribed in that may possibly have held the efficiency of reboxetine in low esteem. Also, whether addition of reboxetine to atypical antipsychotics could result in the same outcome or not, needs its appropriate evaluation. Even though these results are investigative and have to to be confirmed by further analogous studies but nonetheless they were encouraging, since they have illustrated a consequential amelioration of negative symptoms in a group of schizophrenic patients. Small sample size and short duration of experiment were among the major limitations of this assessment.

Conclusion

Reboxetine, as adjuvant to haloperidol, may cause a favorable outcome on behalf of improvement of deficit symptoms of schizophrenia.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.