Hepatitis C in Brazilian Carcerary Micropopulation

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is a disease caused by several etiological agents of universal distribution, which have the hepatotropism in common. They have many similarities from clinical and laboratorial point of view, but they present important epidemiological differences as well as their evolution in each one. Among the most significant progresses in viral hepatitis are the identification of the agents, the development of specific laboratory tests, the screening of infected individuals, and the emergence of protective vaccines [1]. They are considered a worldwide leading cause of liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical follow-up lower than that required for conclusive diagnosis of infection may reflect disease progression, with hepatomegaly as the initial stage of progression of liver disease, evaluating to more severe degrees such as liver cirrhosis, esophageal varices, hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic encephalopathy [2].

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) belongs to the family Flaviridae, genus Hepacivirus, and its genome consists of a single strand of RNA of positive polarity. There is a great variety in the genomic sequence of the virus and its different genotypes were grouped into six main groups and several subtypes [1]. Currently, it is estimated that approximately 2.2 to 3.0% of the world’s population (130-170 million people) are infected with HCV [3].

Identified only in 1989, HCV nowadays represents one of the most relevant public health problems (Passos, 2006). In Brazil, a total of 587,821 confirmed cases of viral hepatitis have been reported in the Information Heath System (SINAN) between 1999 and 2017, from which 200,839 (34.2%) were hepatitis C. The proportional distribution of cases varies among the five Brazilian regions, being 63.2% in the Southeast, 25.2% in the South, 5.9% in the Northeast, 3.2% in the Central West and 2.5% in the North. In 2017, the detection rate in the South region was the highest, with 24.3 cases per 100 thousand inhabitants, followed by the Southeast (15.6), North (6.3), and Central West (5.9). According to an epidemiological bulletin published in 2018 by the Department of Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections, HIV/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis, from the Secretariat of Health Surveillance of the Ministry of Health (DIAHV/SVS/ MS), hepatitis C accounts for the majority of deaths due to viral hepatitis in Brazil, and represents the third largest cause of liver transplantation [4].

The most frequent complaints of chronic hepatitis C are fatigue and sleep disorders. Other symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, anorexia, myalgia, arthralgia, weakness and weight loss; neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression and anxiety) are also common, although these symptoms of chronic HCV infection are not specific in most times. Abdominal pain, pruritus and dark urine are among the most common complaints of patients infected with HCV. The symptoms may lead to a decrease in quality of life, which can be partly explained by the awareness of the infection, and which can be improved after successful treatment. HCV infection has also been associated with cognitive impairment due to mechanisms not well understood. Extra-hepatic manifestations can also be verified, such as hematological, renal, autoimmune disorders, dermatological conditions and Diabetes Mellitus [5].

HCV antibody screenings include high sensitivity screening tests such as ELISA (using recombinant protein or synthetic peptides for anti-HCV uptake) and additional high specificity tests such as immunoblot (RIBA). The gold standard for the diagnosis of HCV infection is the qualitative determination of HCV-RNA through the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Two techniques of molecular biology were also developed for HCV quantification: one of them uses PCR technology and the other is branched DNA. The most accurate method for determining the HCV genotype is the complete identification of the 9,500 nucleotides sequence and the construction of a phylogenetic tree, but this method can only be used in research laboratories, not in clinical ones Brandão et al. [6].

According to the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Hepatitis C and co-infections from the Health Surveillance Secretariat of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the goal of treatment is to obtain sustained virological response (SVR), indicated by the undetectable HCV-RNA, to from 12 to 24 weeks after the end of treatment, avoiding the progression of infection and its consequences (such as cirrhosis, liver cancer and death); increasing the patient’s quality and life expectancy; decreasing the incidence of new cases and reducing the transmission of HCV infection. In Brazil, as in other countries, treatment of hepatitis C is indicated for all patients diagnosed with HCV infection, independent of their acute or chronic forms (regardless of the stage of liver fibrosis) [4]. HCVinfected individuals have large prevalence in people who received blood transfusions and/or blood products before 1992, intravenous drug users, people with tattoos and piercings, chronic injectors, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), transplanted, hemodialyzed, hemophiliacs, prisoners and sexually promiscuous individuals. Thus, HCV routes of transmission are directly associated with the penitentiary environment, increasing the risk of some infections related to unprotected sexual practices and/or injecting drug use with shared utensils Brum et al. [7].

The occurrence of HCV/HIV coinfection has been reported because both share the same mechanisms of transmission, being frequent among illicit drug users and among hemophiliacs, in which occurs between 50% and 75% of the cases. The presence of HIV infection seems to accelerate the evolution of chronic HCV infection to cirrhosis and to hepatic decompensation and/or hepatocellular carcinoma, especially among the most immunodepressed people [1]. Brazil has the fourth largest penitentiary population in the world, leaving behind the United States (2,217,000), China (1,657,812) and Russia (644,237). Until December of 2014 in Brazil, the prison population was 622,202 individuals, from which 55% belonging to the age group between 18 and 29 years. Being a sexually active age group, HIV, HBV, HCV and Treponema pallidum infections compromise the public health of these individuals. The probability of infection is higher in institutionalized settings, such as in penitentiaries, due to overpopulation and precarious situations of confinement (structural problems and problems with hygiene, food and health care). As related, the prevalence of HIV in prisoners varies from 1.19% to 25.0%. In relation to syphilis, this number ranges from 7.4% to 18%, HBV from 6.6% to 17.5% and HCV from 6.3% to 34%. In this way, the penal system can act as a concentrator and disseminator of these infections, being possible the transmission to the outside population in general Silva et al. [8].

Prisons generally do not have room to isolate people with contagious diseases and overcrowding is a risk factor for them. Infection control at correctional establishments may be harmed by limited access to showers, clean clothing supplies, and bans on bleach and condoms. People in jails and prisons are expected to wash their own clothes by hand instead of using institutional laundry services, and that may be insufficient to disinfect clothes. In addition, kitchen workers and barbers in correctional establishments may have inadequate training in infection control [9]. Through a literary review on the prevalence of hepatitis C in prison populations in Brazil, the present study aimed to ratify the high rate of HCV infection present in these individuals deprived of their liberty, which may put at risk other cohabiting prisoners, as well as their close contacts from the outside environment during routine visits.

Methods

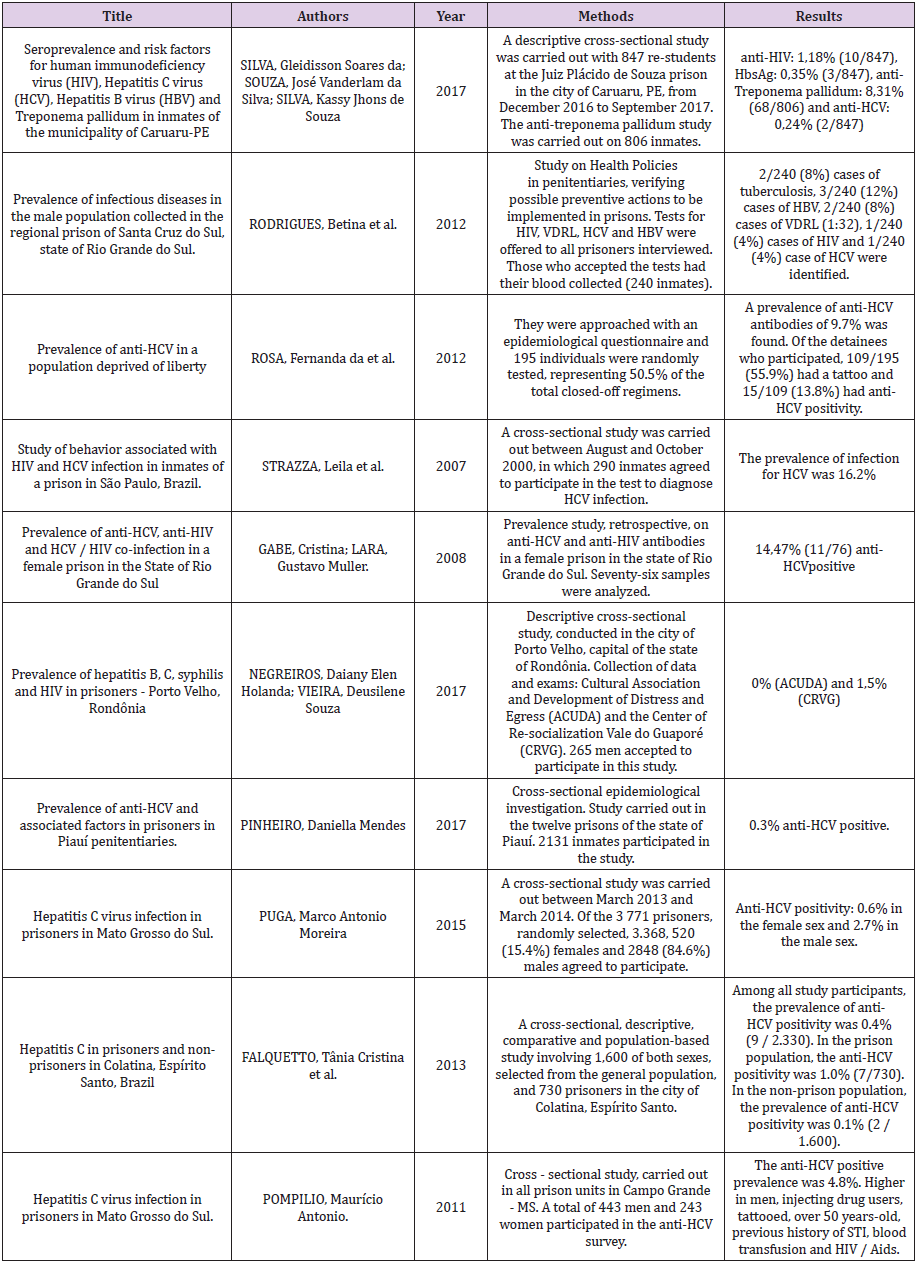

A search was made for works that addressed the topic of Hepatitis C prevalence in prisons in Brazil. The research was conducted in the databases SciELO, LILACS, Google Academic and UpToDate databases on Brazilian works published between 2007 and 2017 (using the keywords “hepatitis C”, “prison” and “antiHCV”). Ten (predominantly cross-sectional) studies were selected and, based on the results found, a discussion about the subject was made, addressing its real situation of hepatitis C in Brazil, especially in the carcerary micropopulation.

Results

According to this review of literature different prevalence of anti-HCV seropositivity in the prison population were showed. Values ranged from 0% to almost 20% as shown (Table 1). In a study performed by Silva et al. [8], when a descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out with 847 re-students at the Juiz Plácido de Souza prison in the city of Caruaru, state of Pernambuco, the antiHCV seropositivity was 0.24% (2/847), and values found in relation to other Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) as HIV, hepatitis B (HBsAg), and syphilis (anti-Treponema pallidum) showed rates of 1.18% (10/847), 0.35% (3/847), and 8.31% (68/806), respectively [10]. in a descriptive cross-sectional study, conducted in the city of Porto Velho, capital of the state of Rondônia, found 0% and 1.5% of anti-HCV seropositivity in two institutions named ACUDA (Associação Cultural e de Desenvolvimento do Apenado) and in CRVG (Centro de Ressocialização Vale do Guaporé), respectively. Still with such low rates, a study carried out in the twelve prisons of the state of Piauí, where 2131 inmates participated in the study, [11] described that anti-HCV was positive in 0.3% in people whom participated the research.

When separating by sex, Puga (2015) demonstrated in 3,771 prisoners randomly selected in Mato Grosso do Sul (84.6% male and 15.4% female) that anti-HCV seropositivity was different between men (2.7%) and women (0.6%). Regarding to individuals in the city of Colatina, state of Espírito Santo, Falquetto et al. [12] found anti-HCV seropositivity in 0.4% among all participants. But, when comparing people inside (730 individuals) and outside (1,600 individuals) prisons it was demonstrated a rate of 1% and 0,1%, respectively, showing a 10-fold risk of infection when cloistered. Other studies showed higher results than previous ones, as Pompilio [13] presented 4.8% of positive results for anti-HCV (which were greater in men, injecting drug users, tattooed, over 50 years-old, previous history of STI, blood transfusion and living with HIV/AIDS) in a total of 443 men and 243 women selected in all prison units in Campo Grande, state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

In a study performed by Rodrigues et al. [14] researching the prevalence of infectious diseases in the male population collected in the regional prison of Santa Cruz do Sul, state of Rio Grande do Sul, the anti-HCV seropositivity was 4%, besides another infections have been detected as tuberculosis, hepatitis B, syphilis and HIV in that population. Another research developed by Rosa et al. [15] in state of Rio Grande do Sul showed a percentage of positive antiHCV in 9.7% individuals. In addition, it was reported that from 195 people who participated 109 had a tattoo, from which 15 had had anti-HCV positive (13.8%). Finally, Strazza et al. [16] in Sao Paulo state and Gabe and Lara [17] in state of Rio Grande do Sul revealed 16.2% and 14.47% of positive anti-HCV, respectively.

Discussion

People deprived of liberty are characterized by marginalization and use of drugs, especially illicit ones. These characteristics together with the poor conditions of confinement (including overcrowding) result in a high prevalence of infectious and contagious diseases as hepatitis C in Brazilian prision Rosa et al. [15]. Although presenting a low prevalence for HCV, Silva et al. [8] verified that in the prison population studied 53.3% were under 30 years old, 4.46% had already received blood transfusion or blood products, 64.3% reported endue tattoo, 6.25% have already used injectable drugs, 37.49% used intranasal drugs, and 41.96% were not in the habit of using condoms in sexual intercourse (112 inmates were characterized for these profiles). With regard to the frequency of risk behaviors, it was observed that 38.9% of subjects with anti-HCV reagent reported injecting drug use. A total of 16 (8.2%) reported to have had blood transfusions before 1993, and 5 (2.6%) reported homosexual relationships (Rosa et al., 2012). Occasional cocaine and crack use in individuals deprived of liberty may reach 56.8%, from which 7.9% use abusively and 2.9% are drug dependent (Prates et al., 2016).

In the study developed by Strazza et al. [16] in a female prison, which had a prevalence of infection for HCV of 16.2%, the aspects related to the risk activities of this group were evaluated in relation to socio-demographic, drug use and sexual practices. Alcohol use was reported by 64% (178/290) of the inmates. It was observed that 69% (200) of them reported using any illicit drug. Marijuana was the drug most cited 61% (143), followed by cocaine 47% (130) and crack 43% (119). Injection drug use was reported by 9% (24) of the inmates, and 44% (11) reported having shared needles with another person. All detainees had had sexual intercourse at least once in their lives. When outside prision women informed having sex with men in 82% (228) of the time; with women 5% (13); with women, but occasionally with men 4% (12); and with men and women alike 3% (6). Regarding sexual intercourse within the prison they informed sex with men 11% (28) of the time; with women 24% (59); with women, but occasionally with men or with men and women also just an affirmative answer for each mode. The non-use of condoms last year in the sexual intercourse with men was reported by 60% (95) of the detainees, and the others reported irregular use. None mentioned their use on a regular basis or have used in sex with women.

HCV has already been isolated in saliva, urine, semen and vaginal secretions. It is known that vertical and sexual transmission is uncommon, and the parenteral route is the main route of HCV infection. The recipients of blood transfusion or transplanted organ (eliminated by blood screening), hemodialysis patients, and mainly injecting drug users are at greater risk. In addition, there is a possibility of transmission of HCV by sharing toothbrushes or shavers, collectively using of non-sterilized piercing materials, such as in dental procedures, tattooing, body piercing, acupuncture, and sharing of objects for use of intranasal cocaine. Prison populations are also characterized as risk groups for infections transmitted primarily by the parenteral and sexual pathways [17].

According to the study by Negreiros and Vieira [10], HCV is more viable in the environment when compared to HIV. This way, HCV infection through the parenteral route is more effective, being ten times more infectious than HIV in exposure to sharps. Therefore, for HCV infection drug addiction of intravenous drugs is the main parenteral risk factor. In their study, subjects who tested positive for hepatitis C had an average age of 32 years and did not have a common determining factor. However, one claims to have performed blood transfusion and other claims to be injecting drug users, both at risk for HCV infection. In the study developed by Pinheiro [11], the prevalence of anti-HCV seropositivity was 0.3%, being observed as factors associated with blood transfusion before 1993 and use of glass syringes previously. Overall, in the study population, 78.7% reported use of alcohol, which beer is the most frequent beverage (91.2%), 57.6% using some type of illicit drug, which whom 58.6% reported using it daily. Regarding risk factors for HCV infection, 2.5% received blood transfusion before 1993, 55% share sharps, 60.4% have tattoos, 13.9% use piercing, and 1% reported previous use of syringes of glass. In this way, the sexual risk behaviors and the low level of information that the inmates have on hepatitis C were verified.

In the study by Puga [18], the prevalence of HCV exposure was 2.4% (80/3368) and in females (0.6% of 520) was lower than in males (2.7% of 2848). In relation to anti-HCV seropositivity, 46.7% of men and 66.6% of women had other STIs. HCV infection was significantly associated with men over 30 years old, time of incarceration, alcohol consumption, crack, heroin and hashish, injecting drug use, needle and syringe sharing, blood transfusion history, concomitant STI’s, surgery, seropositivity for HIV and more than five sexual partners in the last five years. In the Pumpilo study [13], from 686 individuals tested for HCV 4.8% (33/686) presented anti-HCV seropositivity. In an analysis by sex, the prevalence in women (0.8%) was also lower than in men (7%). In general, of those 33 who presented seroprevalence of HCV infection, nine reported having never used a condom, 11 had HIV/AIDS, 18 reported injecting drugs, 12 received blood transfusion, 25 had tattoos, and two had piercings. Similar data on the presence of tattooing in patients who had positive anti-HCV were found in the study by Rosa et al. [15] in which the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies was 9.7%. Also, from 195 individuals who participated the study 109 had a tattoo. Of these, 13.8% (15/109) presented anti-HCV positivity.

As it can be seen, people inside prisons have many risk factors for HCV infection, as well as other STIs, as they live in poor hygiene conditions and overcrowding, sharing their personal tools, using illicit drugs, and having unprotected sex even with their casual partners or with their close contacts in intimate visits. In this way, the prison micropopulation becomes a group of individuals capable of perpetuating the HCV infection for many years ahead, regardless of the effective treatment used if preventive measures are not taken.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is an urgent need for public health agencies to plan measures that will diagnose and treat individuals infected with HCV in prison populations, as well as educate about preventive measures and alert about the real forms of infection, trying to reduce the alarming rates of infected people in such environments and the spread to the general population. Not least, it must be remembered that there is a high risk of coinfection, and the same measures should be taken against other STIs.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.