New Use of Rapamycin Stent in Non-Responding Facial Lymphatic Malformation

Introduction

Vascular anomalies represent a diagnostic and therapeutic difficulty. The classification system of the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) divides them in two groups: tumors and vascular malformations based on clinical, genetic and pathological findings [1]. Lymphatic malformations (LM) -low flow vascular malformations- are classified as macrocystic, microcystic or mixed [1-3]. The incidence of LM reaches 1.2–2.8 per 1,000 births and 2.8 patients per 100,000 hospital admissions [1]. They are located in the head and neck area in 70% of the cases, and their growth is proportional to the patient’s development unless infection, trauma or hormonal changes are present [1,4]. Imaging is an essential diagnostic tool, based on the presence of thin-walled cysts of variable size, generally clustered in the affected area. Depending on the location, depth and size of the lesion, the most useful tests are ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance (MRI). [2]. The classic therapeutic approach includes sclerotherapy or surgical excision, depending on each case. However, in some cases an optimal result is not accomplished [5]. Recently, angiogenesis inhibitors agents such as Rapamycin (Sirolimus) have been used with promising outcomes. In particular cases when LM or venouslymphatic malformations have not responded to other treatments, oral Rapamycin has been reported to be successful [1,6]. Herein, we report a clinical case of LM nonresponding to conventional management treated with an intralesional biological therapy: Rapamycin stent. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports on the use of this kind of stent in LM.

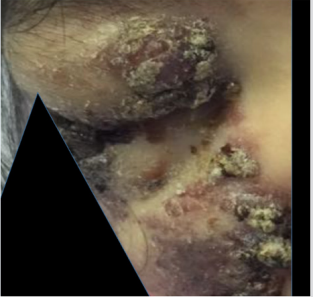

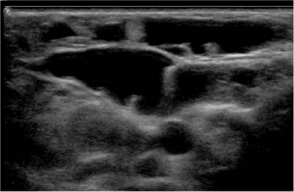

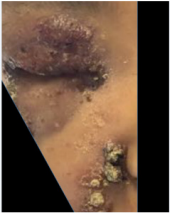

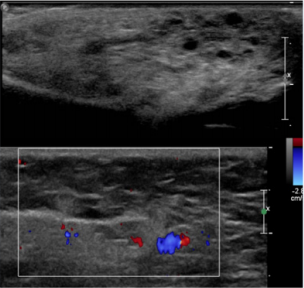

A six-year-old female patient presented with a large congenital right hemifacial tumor, with slow progressive growth (Figure 1). The sequential imaging control with US and MRI exhibited a LM with macrocystic and microcystic components in the right hemiface (Figures 2 & 3). The patient displayed an inadequate response to treatment with Sildenafil. Also, multiple sclerotherapy sessions were performed with suboptimal tumor control. At the four years of age, she showed a persistent volume increase of the LM in the right maxillary and temporal area, compromising vision. Emphasis on the importance of an effective treatment was made due to the risk of amblyopia. As new imaging tests showed a progressive growth of the lesion. Supplementary sclerotherapy sessions were made with partial response. Because of the ophthalmic urgency and the poor response after several treatments, a Rapamycin based therapy was proposed to the family, offering to install a local device which was safely used previously in cardiac procedures. They signed the informed consent approved by the ethics committee. The interventional radiologist installed an intralesional Rapamycin stent (Ultimaster 2.5 mm diameter min. guiding catheter 1.42 mm Lot 170726) (Figure 4). The percutaneous guide was used through the lymphatic cyst. The procedure was well tolerated, without side effects. Clinical improvement was immediately evident, with substantial pain relief, along with a significant decrease in the tumor size and restored orbital aperture (Figure 5). Two US follow ups after the procedure, showed small cysts and decreases in the volume of the macrocysts. Some inflammatory change in the periorbital and cheek subcutaneous tissue and no abnormal vessels are depicted in Doppler color US (Figures 6 & 7).

Figure 2: US shows multiple confluent thin wall cysts in the right hemiface concordant with macro and microcystic LM.

Figure 3: US shows multiple confluent thin wall cysts in the right hemiface concordant with macro and microcystic LM.

Figure 5: Six-year-old female patient after Rapamycin stent treatment with decreased tumor size and better orbital aperture.

Figure 6: US in the periorbital and cheek region. Small cysts and decreases in the volume of the macrocysts. Some inflammatory change in the periorbital subcutaneous tissue and no abnormal vessels are depicted in Doppler color US.

Figure 7: US in the periorbital and cheek region. Small cysts and decreases in the volume of the macrocysts. Some inflammatory change in the periorbital subcutaneous tissue and no abnormal vessels are depicted in Doppler color US.

Discussion

Vascular anomalies represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. According to the ISSVA classification, they can be divided in tumors and malformations, based on clinical, pathologic and genetic features [1]. Lymphatic malformation (LM) corresponds to a low-flow vascular malformation, with an incidence of 2.8 patients per 100,000 hospital admissions [1]. Frequent in head and neck location, 90% detected before the age of 2 years [4]. LM corresponds to vasculogenesis disorders with persistent growth over time. On histology, it is formed by cysts lined by an endothelium containing amorphous lymph [1]. The LM have a wide clinical spectrum. The cysts can be few and small or in the other side present with a severe hypertrophy and deformation with the subsequent complications and functional limitation. Spontaneous regression is rare [4]. They can present high morbidity and mortality according to their size and location area, with functional impairment, aesthetics changes, pain and other complications such as altered feeding [3]. Among the complications in the facial area are infection, hemorrhage, exophthalmos, and amblyopia. Facial LM and their variants can have a greater therapeutic complexity.

In the imaging diagnosis of vascular malformations ultrasound represents a fundamental pillar, based in the gray scale imaging and Doppler color. Also, the MR is very important specially in extense, severe or vital structures compromise [2]. US allows evaluating the presence of cysts, the different layers compromised, presence of solid tumors or calcification, small part hypertrophy and vascular pattern of the lesion. When a vascular malformation is suspected the existence of anomalous arterial or venous vessels can oriented to a high or low flow malformation. In LM the presence of cysts is the key point. US can differentiate in microcystic (cyst less than 1 cm), macrocystic (cysts bigger than 1 cm) o mixed LM, [1] and can suggest the presence of LM complications. In US we can observe micro or macrocysts distributed in a focal area or more spread areas. The cysts are anechogenic with thin walls. Sometimes some echoes or level inside the cyst can be observed. These are more frequent in the presence of complications. The cyst can be located in the superficial layers or depth in the body. The subcutaneous location can be associated to adipose tissue hypertrophy. In Doppler color small thin venous vessels can be observed in the septa between the cyst. When the vascular malformation is a combined malformation abnormal venous or arteries can be present.

The proposed treatment depends on the severity of LM. It has to be personalized and that is why it is important to have a of a multidisciplinary group of specialists in charge of these patients. In macrocystic LM sclerotherapy and surgery can be used [1,7]. Either alone or combined with embolization is a valuable treatment. To date, interventional radiology is the top line treatment for vascular malformations in many reference centers [7]. Large microcystic or mixed malformation are a therapeutic problem, sometimes progressing with the treatment. Rapamycin is a potent mTOR inhibitor (mammalian target of Rapamycin), is a serine/threonine protein kinase, which modulates the signaling pathway of angiogenesis and cell proliferation, decreasing the vascular endothelial growth factor. mTOR is suspected to play a role in the pathogenesis of some vascular anomalies. In 1970 sirolimus (Rapamycin) an inhibiting mTOR compound was identified. In 2015 this drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The literature suggests that Sirolimus is an effective therapy for LM but has many side effects and its bioavailability is extremely variable with complex plasmatic monitoring being required; so, a local controlled release increases the profile of safety and efficacy [6]. It appears as a useful therapy in extensive nonresponding LM, expanding the therapeutic possibilities [1].

The use of a bioresorbable polymer of a sirolimus-eluting stent is a daily practice in interventional cardiology. Rapamycin stents have been extensively used in cardiology with safety protocols according to the FDA [8,9]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the use of Rapamycin stents in the treatment of vascular malformations. In our case the unsatisfactory evolution of the patient after conventional treatment with progression of tumor size, pain, visual compromise, and life quality led us to an innovative treatment option and the interventional radiologist suggested the introduction of the percutaneous Rapamycin stent. The patient responded favorably with the Rapamycin stent, improving her optical field, functionality and aesthetics. A strict quarterly follow-up has been pursued for nine months until now, with no adverse effects reported.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of local Rapamycin through stents as carriers should be considered as a therapeutic alternative in the treatment of extensive non-responding LM. To date the patient has exhibited persistent stable evolution and adequate tolerance, avoiding the side effects of systemic rapamycin therapy. The necessity of a multidisciplinary approach is fundamental specially in severe cases of LM. Its permits the adequate follow up, treatment planning and orientation of the patient and family group.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.