Differential Effects of Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Saturated Fatty Acids on Lipotoxicity and Neutral Lipid Accumulation in Neuro-2a Cells

Introduction

Long-chain free fatty acids (FFA) play many important roles in

cell growth and metabolism, as structural components of biological

membranes and as mediators of cell signaling. Common longchain

FFA found in human plasma include saturated fatty acids

(SFA), such as palmitic acid (PA; 16:0) and stearic acid (18:0), and

unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) which may vary in the position of the

double bond and in the degree of unsaturation, including oleic acid

(OA; 18:1n-9), linoleic acid (LA; 18:2n-6), α-linolenic acid (ALA;

18:3n-3), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n-3) [1]. After entry

into cells, fatty acyl CoA synthetase catalyzes the conversion of fatty

acids into fatty acyl-CoA, which may then be catabolized to generate

energy or anabolized to produce a range of molecules including

second messengers, hormones, and diacylglycerols (DAG). DAG

may enter the phospholipid synthesis pathways or be converted to triacylglycerols (TAG), which may be subsequently incorporated

into lipid droplets (LD) [2].

One of the hallmarks of metabolic diseases is the accumulation of excess fatty acids in non-adipose tissues [3], which may lead to deleterious lipotoxic effects including cellular dysfunction and death [4]. PA has been reported to induce lipotoxicity in many cell types, including cardiomyocytes [5], hepatocytes [6], and neural stem cells [7,8]. In contrast, ω-3 fatty acids enhance hippocampal neurogenesis and promote synaptic plasticity [9]. OA ameliorates PA-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in exocrine pancreas cells [10] and HepG2 cells [11]. LA also protects cultured mouse embryonic cortical neurons from glutamate-induced excitotoxicity [12]. There is evidence suggesting that UFA-induced esterification and sequestration of PA into neutral lipids and LD may contribute to their lipoprotective effects. LD, consisting of a neutral lipid core containing TAG, sterol esters, and fatty acids surrounded by a monolayer of phospholipids embedded with numerous proteins, is found in many types of cells. LD not only acts as lipid storage sites, but also participates in membrane biogenesis, hormone synthesis, intracellular signaling, protein storage, and protein degradation [13,14].

LD biogenesis and degradation has been suggested to play important roles in buffering the intracellular levels of toxic lipid species [14]. For example, arachidonic acid (ARA; C20:4n-6)- induced LD formation is associated with its protection against PA-induced lipotoxicity in C2C12 myocytes [15]. OA-induced TAG synthesis and LD formation is associated with its protection against PA-induced lipotoxicity in primary syncytiotrophoblasts [16], CHO cells [17], and β-cells [18]. Fatty acid accumulation is reportedly enhanced in the brains of metabolic syndrome patients [19]. While neurons are not energy-storing cells and their use of fatty acids as an energy source is minimal, they do contain LD [20]. High fat diet causes obesity and loss of myenteric neurons in Swiss mice [21]. High fat diet also affects the hypothalamic proteome indicative of cellular stress, altered synaptic plasticity and mitochondrial function in mice [22]. This study was therefore designed to examine how SFA and UFA differentially affect cell viability and neutral lipid accumulation in murine neuroblastoma Neuro-2a (N2a) cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

LA, OA, PA, ALA, DHA, and fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). To prepare BSA-conjugated fatty acids, fatty acids were dissolved in 100% ethanol at 400 mM. FAs were then conjugated with BSA in PBS at 2.5:1 molar ratio to make 5 mM FA solutions [23]. Conjugated fatty acids were then filtered, aliquoted, and stored at -80°C.

Cell Culture

Murine Neuro-2a (N2a) neuroblastoma cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). These cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential media (Lonza; Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1% (v/v) penicillinstreptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and maintained in a humidified environment with 5% CO2 at 37°C. All experiments were conducted with cells passaged fewer than 20 times.

MTT Assay

Cell viability was determined based on the ability of cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)- dependent oxidoreductase enzymes to reduce the tetrazolium dye, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich), to insoluble formazan. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 1.0x104 cells/well. After overnight incubation, cells were administered with different treatments in serum free media with BSA as the negative control. At 2 h prior to the completion of treatment, MTT reagent was added to the wells at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubated for another 2 h. At the end of incubation, the formazan precipitates were solubilized in isopropanol with 0.04 M HCl, and the absorbance was read at 570 nm and 650 nm for reference absorbance to correct for nonspecific background absorption on the VarioSkan Lux microplate reader (Thermo; Waltham, MA, USA).

Annexin V Assay

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1.0 x 105 cells/well. After overnight incubation, cells were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of PA or BSA as the negative control in serum free media. At the end of treatment, cells were collected by trypsinization, spun down, and then washed with binding buffer (140 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 0.75 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM CaCl2) before being resuspended in staining solution containing 5% Annexin V-FITC (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA, USA) and 2 μg/ mL propidium iodide (PI). Following incubation at RT for 15 m in the dark, cells were analyzed on the MACSQuant Analyzer 10 flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec; Auburn, CA, USA). The fluorescent intensities of FITC and PI were quantified. The central population of forward scatter (FSC) vs. side scatter (SSC) flow cytometry events was inclusively gated to omit debris. Singlets were then sub-gated by FSC-A vs. FSC-H. Flow cytometry data were then analyzed using FlowJo10 (BD Biosciences; Ashland, OR, USA).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) Assay

TUNEL assay was performed following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in chamber slides at 2.5 x 104 cells/chamber. After overnight incubation, cells were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of PA or BSA control in serum free media. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 m at 4°C, cells were washed, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 m, washed, and then incubated with a reaction mix containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and fluorescein-12- dUTP (Roche; Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 90 m at 37°C. After washing, cells were stained with PI, and then visualized under the FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus; Center Valley, PA, USA).

Neutral Lipid Quantitation by Flow Cytometry

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 0.5 x 105 cells/well. Following treatment, cells were incubated with 5 μM 4,4-Difluoro-1,3,5,7,8-Pentamethyl-4-Bora-3a,4aDiaza-s-Indacene (BODIPYTM 493/503; ThermoFisher; Waltham, MA, USA), a fluorescent marker for neutral lipids, in serum-free media for 30 m at 37°C. Cells were then trypsinized, rinsed, and resuspended in ice-cold PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Neutral Lipid Imaging

For bright-field imaging of neutral lipids, cells were seeded on coverslips and treated as indicated. At the end of treatment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 m at 4°C, washed, equilibrated in 60% isopropanol for 5 m, and incubated with 0.5% Oil Red O for 20 m at room temperature. Cells were then washed, mounted, and imaged under the Motic Panthera light microscope (Schertz, TX, USA). For fluorescent imaging of neutral lipids, cells were incubated with 2 μM Nile Red or 5 μM BODIPYTM 493/503 for 30 m following treatment. Cells were then rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20m at 4°C. After rinsing with PBS, cells were stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI for 10 m in the dark, and then imaged under FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus; Center Valley, PA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (Graphpad Software; San Diego, CA, USA) and presented as mean ± SEM. Oneway or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PA Treatment Reduced the Viability of N2a Cells

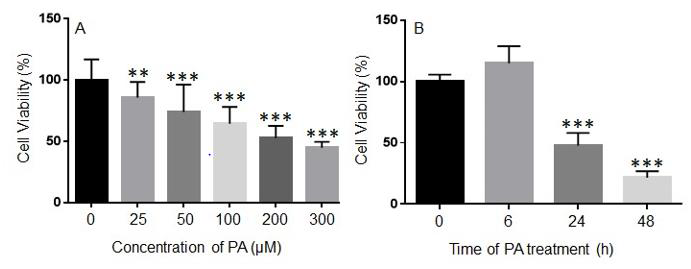

To determine the effects of PA treatment on the viability of N2a cells, N2a cells were treated with different concentrations of PA ranging from 25 μM to 300 μM or BSA control in serum free media for 24 h, and their viability was assessed by MTT assay. The viability of N2a cells was significantly decreased following 24 h treatment with 25 μM PA as compared to the BSA control. As the concentration of PA was increased, the viability of N2a cells continued to decrease (Figure 1A). N2a cells were then treated with 200 μM PA or BSA control for 6, 24, or 48 h. At 6 h after PA treatment, no significant difference in cell viability was detected. However, 200 μM PA significantly decreased the viability of N2a cells at 24 h and 48 h post-treatment (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Concentration- (A) and time-dependent (B) effects of palmitic acid (PA) on the viability of N2a cells. N2a cells were treated with different concentrations of PA for 24 h (A) or with 200 μM PA for different periods of time (B) in serum free media, and their viability was assessed by MTT assay. The values presented were representative of three independent experiments with triplicate measurements (mean ± SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. **p < 0.01 vs. control; ***p < 0.001 vs. control.

PA Treatment Induced Cell Death in N2a cells

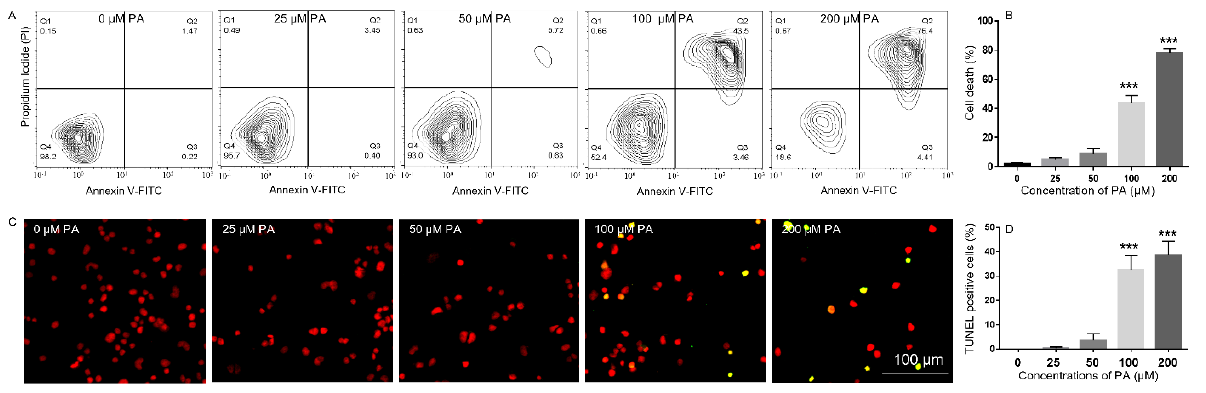

To determine whether PA-induced decrease in N2a viability was associated with increased cell death, N2a cells were treated with different concentrations of PA ranging from 25 μM to 200 μM or BSA control in serum free media for 24 h, stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of Annexin V-positive and PI-positive cells in BSAtreated control was minimal. Treatment with 25 μM PA did not significantly enhance the number of Annexin V- or PI-positive cells. The number of Annexin V- and PI-positive cells began to increase following treatment with 50 μM PA for 24 h and was significantly enhanced following treatment with 100 μM PA for 24 h. This trend continued to amplify in cells treated with 200 μM PA (Figures 2A & 2B). PA-induced cell death was also examined by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. There were hardly any cells stained positive by TUNEL assay in BSA-treated samples. Treatment with 25 μM or 50 μM PA for 24 h did not significantly increase the number of TUNEL positive cells. The percentage of TUNEL positive cells was significantly increased following treatment with 100 or 200 μM PA for 24 h (Figures 2C & 2D).

Figure 2: Analysis of PA-induced N2a cell death by Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining (A-B) and TUNEL assay (C-D). (A-B), N2a cells were treated with 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μM PA for 24 h in serum-free media followed by staining with FITCconjugated Annexin V and Propidium Iodide (PI) and analysis of fluorescence by flow cytometry with representative contour plots of compensated FITC vs. PI channels shown in A and combined percentage of FITC+/PI- and FITC+/PI+ cells shown in B. (C-D), N2a cells were treated with 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μM PA for 24 h in serum-free media followed by TUNEL assay with representative confocal microscopy images of Fluorescein-12-dUTP and PI staining shown in C, and percentage of TUNEL+ cells shown in D. The values presented were representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ***p < 0.001 vs. control.

PA-Induced Decrease of N2a Viability Was Not Alleviated by NAC or 4-PBA

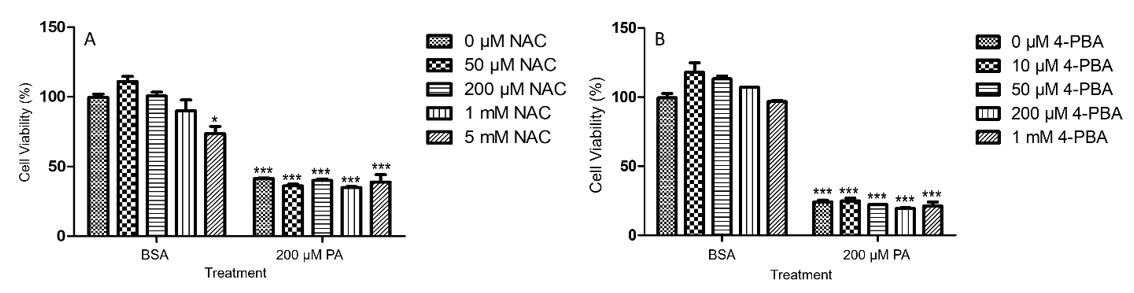

Figure 3: PA-induced decrease of viability in N2a cells was not attenuated by NAC (A) or 4-PBA (B). N2a cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of NAC (A) or 4-PBA (B) for 0.5 h followed by treatment with 200 μM PA or BSA as control for 24 h in serum free media, and their viability was assessed by MTT assay. The values presented were representative of three independent experiments with triplicate measurements (mean ± SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ***p < 0.001 vs. control.

To determine whether PA-induced decrease of N2a viability could be alleviated by antioxidants, N2a cells were pre-treated with 50 μM, 200 μM, 1 mM, or 5 mM of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) for 0.5 h followed by treatment with 200 μM PA or BSA for 24 h in serum free media. NAC alone slightly decreased N2a viability at 5 mM as compared to the BSA control without any NAC. NAC at all concentrations tested did not significantly attenuate PA-induced decrease in N2a viability (Figure 3A). To determine whether PAinduced decrease of N2a viability could be alleviated by inhibitors of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, N2a cells were pre-treated with 10 μM, 50 μM, 200 μM, or 1 mM 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) for 0.5 h followed by treatment with 200 μM PA or BSA for 24 h in serum free media. While PA induced significant decrease of N2a viability, 4-PBA at all concentrations tested did not significantly attenuate PA-induced decrease in N2a viability (Figure 3B).

Unsaturated Fatty Acids Abrogated PA-Induced Decrease of N2a Viability

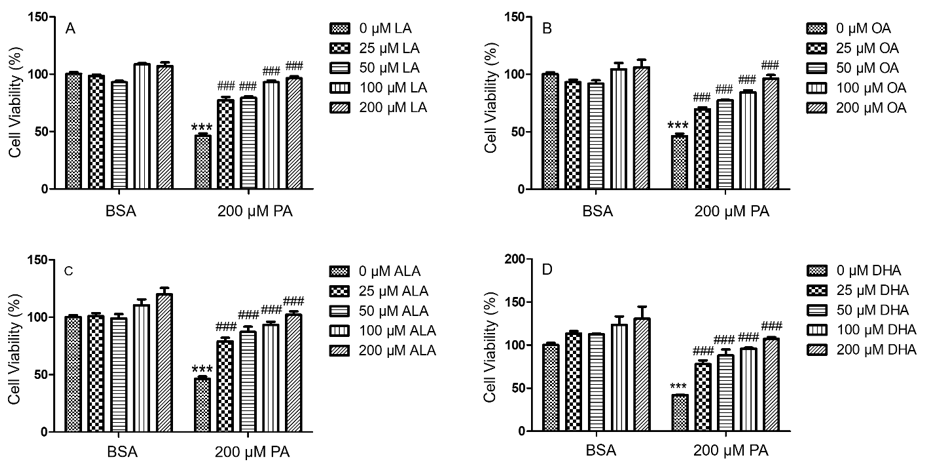

To investigate whether unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) mitigated PA-induced decrease of N2a viability, N2a cells were treated with 25, 50, 100, or 200 μM of different UFA, such as LA, OA, ALA, and DHA, together with 200 μM PA or BSA in serum free media for 24 h, and their viability was determined by MTT assay. Each UFA examined was found to significantly attenuate PA-induced decrease of N2a viability starting at concentrations as low as 25 μM. At 100 and 200 μM, OA, LA, ALA, and DHA abolished the PA-induced decrease in N2a viability (Figure 4).

Figure 4: PA-induced decrease in BV2 viability was abolished by LA (A), OA (B), ALA (C), and DHA (D). BV2 cells were treated with 0, 25, 50, 100, or 200 μM of LA (A), OA (B), ALA (C) and DHA (D) together with 200 μM PA or equivalent volume of BSA control in serum-free media for 24 h, and their viability was assessed by MTT assay. The values presented were representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ***p < 0.001 vs. BSA control; ###p < 0.001 vs. 200 μM PA.

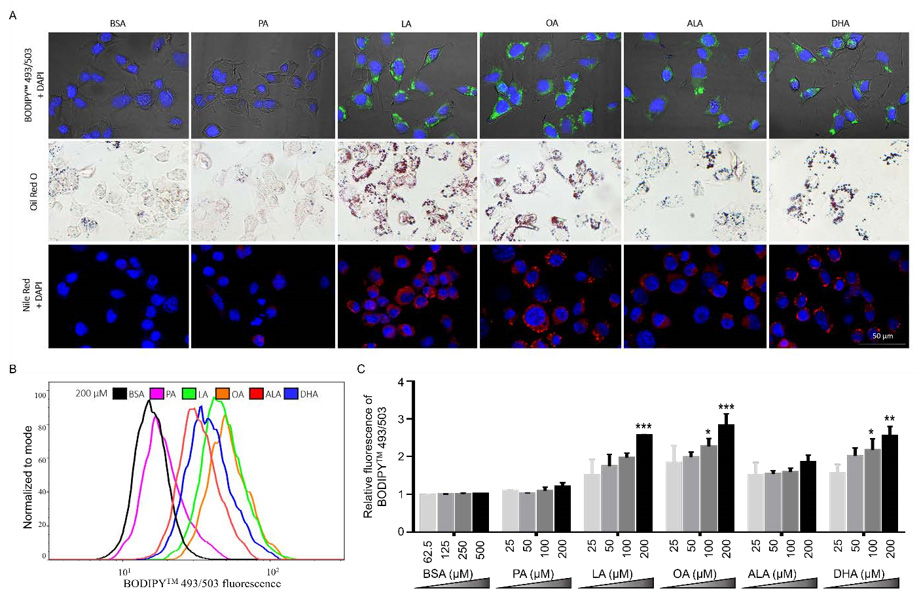

SFA and UFA Differentially Modulated Neutral Lipid Accumulation

To examine the effects of different FFA on the accumulation of neutral lipids, N2A cells were treated with 200 μM FFA or BSA control for 6 h, then incubated with different lipophilic dyes, including 4,4-Difluoro-1,3,5,7,8-Pentamethyl-4-Bora-3a,4a-Diazas- Indacene (BODIPYTM 493/503), Oil Red O, and Nile Red, and examined under microscopy. BSA-treated cells exhibited only basal level neutral lipid staining by BODIPYTM 493/503, Oil Red O, and Nile Red. Neutral lipid staining in PA-treated cells was comparable to basal level staining in BSA controls as detected by BODIPYTM 493/503, Oil Red O, and Nile Red. In contrast to BSA and PA, cells treated with LA, OA, ALA, or DHA all exhibited more intense neutral lipid staining as detected by all three lipophilic dyes. Moreover, neutral lipid staining appeared to be concentrated in particulates in UFA-treated cells and more diffuse in PA-treated cells, suggesting that UFA not only increased the amount of neutral lipids, but also promoted formation of LD (Figure 5A).

Differential neutral lipid accumulation following UFA and SFA treatment was also quantitated by BODIPYTM 493/503 staining via flow cytometry. PA did not dramatically alter the fluorescence intensity of BODIPYTM 493/503 staining at all concentrations tested (Figures 5B & 5C). Consistent with microscopic examination of neutral lipid staining as shown in Figure 5A, the amount of BODIPYTM 493/503 staining was significantly enhanced by LA, OA, and DHA at 200 μM as compared to BSA control (Figures 5B & 5C). BODIPYTM 493/503 staining appeared consistently greater in ALA-treated cells compared to BSA control, but the amplitude of this increase did not reach statistical significance (Figures 5B & 5C). These data suggest that UFA, but not SFA, promoted the accumulation of neutral lipids in N2a cells.

Figure 5: Neutral lipid accumulation in N2a cells following treatment with different FFA.

(A) Representative images of N2A cells treated with 200 μM PA, LA, OA, ALA, DHA, or BSA control for 6 h, stained with

DAPI (blue) and BODIPYTM 493/503 (green) and visualized under confocal microscopy, or stained with Oil Red O (red) and

visualized under bright-field microscopy, or stained with DAPI (blue) and Nile Red (red) and visualized under confocal

microscopy.

(B) Representative overlayed flow cytometry histograms of cells treated with 200 μM FFA or BSA for 6 h and stained with

BODIPYTM 493/503.

(C) Relative quantitation of lipid accumulation in N2a cells treated with different concentrations of FFA or BSA control for

6h as analyzed by flow cytometry following BODIPYTM 493/503 staining. Presented data (mean ± SEM) were representative

of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple

comparison test. *p < 0.05 vs. corresponding BSA control; **p < 0.01 vs. corresponding BSA control; ***p < 0.001 vs. corresponding

BSA control.

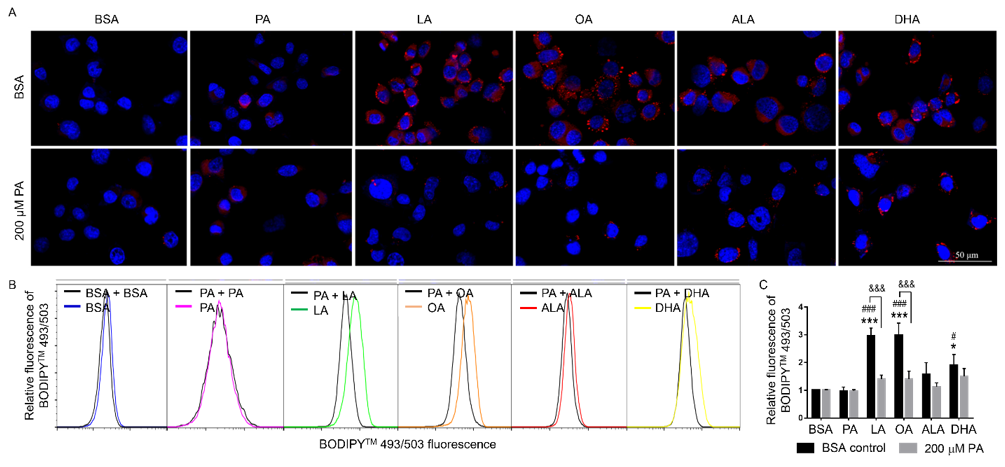

UFA did not Significantly Increase the Amount of Neutral Lipid Accumulation in PA-Treated Cells

To examine whether UFA-induced synthesis of neutral lipid accumulation was involved in the protective effects of UFA against PA-induced decrease of N2a viability, N2a cells were treated with 200 μM LA, OA, ALA, or DHA with or without 200 μM PA for 24 h, stained with Nile Red and DAPI, and then visualized under confocal microscopy. While UFA enhanced neutral lipid accumulation and LD formation compared to cells treated with BSA or PA alone, the total amount of neutral lipid staining in cells co-treated with UFA and PA appeared comparable to that in PA-treated cells, suggesting that UFA may not enhance neutral lipid accumulation in PA-treated cells. The neutral lipid staining did appear to be more concentrated in particulates in cells co-treated with UFA and PA but more diffuse in PA-treated cells, suggesting that UFA induced LD formation in PA-treated cells (Figure 6A). Neutral lipid accumulation was also quantified by flow cytometry following BODIPYTM 493/503 staining, which confirmed that the amount of neutral lipid staining in cells co-treated with UFA and PA was comparable to that in PAtreated cells (Figures 6B & 6C). These studies suggest that UFA may induce LD formation in PA-treated cells even though UFA did not seem to enhance the total amount of neutral lipid staining in these cells in PA-treated cells.

Figure 6: Neutral lipid accumulation in N2A cells co-treated with 200 μM PA and different FFA.

A. Representative images of N2A cells co-treated with different FFA together with 200 μM PA or BSA for 6 h, stained with

Nile red (red) and DAPI (blue), and visualized under confocal microscopy.

B. Representative flow cytometry histograms of cells co-treated with different FFA together with 200 μM PA or BSA as

control for 6 h and stained with BODIPYTM 493/503.

C. Relative quantitation of lipid accumulation as analyzed by flow cytometry following BODIPYTM 493/503 staining.

Presented data (mean ± SEM) were representative of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using

two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05 vs. BSA control; ***p < 0.001 vs. BSA control; #p <

0.05 vs. 200 μM PA; ###p < 0.001 vs. 200 μM PA; &&& p < 0.001 vs. corresponding BSA-treated cells.

Discussion

In the brain, lipids are involved in many functions including its development, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, myelin sheath formation, and signal transduction [24]. Alterations of lipid homeostasis are associated with brain injury and with metabolic and neurologic disorders [25]. The goal of this study was to examine how UFA and SFA differentially affected the viability and neutral lipid accumulation in N2a cells. Our studies showed that PA, a SFA, significantly decreased N2a cell viability and induced significant cell death while the UFA, such as LA, OA, ALA, and DHA, rescued PA-induced decrease of N2a viability. We also found that UFA significantly increased neutral lipid accumulation and LD formation while PA did not. Moreover, the amount of neutral lipid staining in cells co-treated with UFA and PA was comparable to that in BSA- and PA-treated cells with the staining more in particulates in cells co-treated with UFA and PA, suggesting LD formation.

Much of the neutral lipid staining in cells co-treated with UFA and PA did appear more concentrated in particulates than PAtreated cells, suggesting that UFA induced LD formation in PAtreated cells. Future studies may further explore whether UFAinduced LD formation may contribute to UFA-mediated protection against PA lipotoxicity. An alternative mechanism may involve ceramide formation in PA lipotoxicity. PA has been reported to increase ceramide content in murine enteroendocrine cells, which is reduced by OA [31]. Both cell culture and animal studies suggest that DHA may attenuate PA- or high fat diet-induced ceramide lipotoxicity [32].

In summary, our study demonstrated that PA decreased cell viability and induced cell death in N2a cells. PA-induced lipotoxicity was not alleviated by pre-treatment with NAC, an antioxidant, or 4-PBA, an inhibitor of ER stress, suggesting that oxidative stress and ER stress may not play a key role in PA lipotoxicity in N2a cells. In contrast, all the UFAs tested, namely LA, OA, ALA, and DHA, protected N2a cells against PA lipotoxicity. We also found that LA, OA, and DHA, but not PA, significantly enhanced neutral lipid accumulation and LD formation, that UFA did not enhance the total amount of neutral lipid accumulation in PA-treated cells, and that UFA may induce LD formation in PA-treated cells.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.