Intraoperative Cone Beam CT in Hybrid Operating Room Set-Up as An Alternative to Postoperative CT for Pedicle Screw Breach Detection

Introduction

Accurately positioned pedicle screws offer optimal

biomechanical fixation, making them a well-accepted treatment

choice for a variety of spine pathologies [1,2]. However, up to

42% of pedicle screws were reported to be malpositioned [3,4].

While initially silent clinically, these may eventually present

with an unstable construct, reduced fusion, pseudoarthrosis and

accelerated adjacent-level degeneration [5]. In comparison to CT,

radiography detects only 52% of misplaced screws [6,7], making

intraoperative CT imaging necessary, especially for complex

deformity, to avoid revision surgeries. Availability of intraoperative

3D imaging resulted in revision of 9% of screws intraoperatively,

corresponding to 35% of the treated patients. Lower threshold

for intraoperative revisions based on objective intraoperatively

available imaging data, leads to fewer secondary revision surgeries

[8]. Avoidance of postoperative revisions makes the initial

investment in intraoperative 3D imaging technologies economically

more attractive [9].

Hybrid operating rooms (OR) equipped with a motorized C-arm coupled with a radiolucent surgical table as well as with integrated navigation capabilities, have been recently used for spine surgery [10]. The C-arm provides intraoperative cone-beam CT (CBCT) imaging. The purpose of this cadaver study was to determine the diagnostic performance of intraoperative CBCT using a C-arm in a hybrid OR for identifying screw misplacements in comparison to gold-standard postoperative CT. To put our results in perspective, a sytematic literature review of studies comparing intraoperative 3D imaging for screw misplacements with postoperative CT was conducted.

Materials & Methods

Surgical Technique

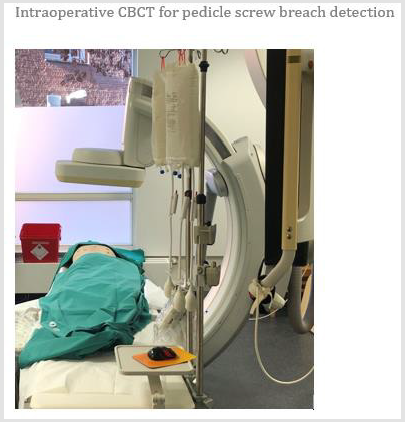

Surgeries were performed by one surgeon in a hybrid OR (AlluraClarity Flexmove, Philips, the Netherlands), (Figure 1). Cadavers were placed prone on the operating table, adhesive skin markers applied and a planning CBCT scan obtained. Pedicle screw trajectories were planned using Augmented Reality Surgical Navigation system (ARSN, Philips, the Netherlands) [11]. Pedicles were instrumented bilaterally from C7 to L5 using a tracked Jamshidi needles, aligned along the planned trajectory. Cannulated pedicle screw sizes were 5.5 x 40 mm from C7 to T9; and 6.5 x 45mm from T10 to L5.

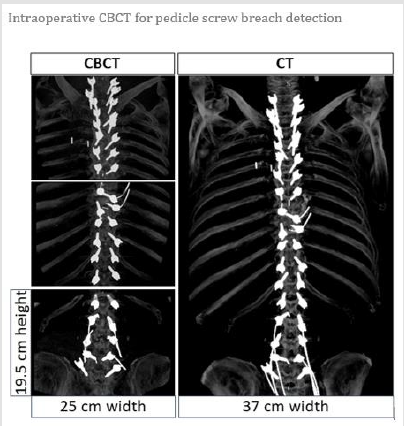

CBCT Imaging: The Study Group

The C-arm was positioned on the side, orthogonal to the operating table along the axial plane of the patient and rolled in this plane to perform CBCT optimized for spine imaging (XperCT Spine, Philips, the Netherlands). The CBCT reconstruction is the result of 302 x-ray projections acquired over a 180-degree clockwise rotation, starting with the x-ray tube on the right side of the table. The acquisition settings were 120 nominal kV tube voltage and modulated tube current-exposure time (mAs) generated by the automatic exposure control which is estimated based on patient size thickness at each angular projection during the rotation. Radiation dose-area products were collected from the ra-diation Dose Structured Report (RDSR) and converted to patient Effective Dose (ED). The CBCT reconstruction corresponds to a 512x512x396 matrix with isotropic voxels of 0.49mm. Consequently, the dimension of the imaged region of interest (ROI) corresponds to a 25x25cm in the axial plane by 19.5 cm in the cranial-caudal direction [12], (Figure 2).

CT: The Reference Group

Default settings for spine imaging on a 16-slice CT scanner was used to image the cadavers (Brillance 16, Philips, the Netherlands). CT image reconstructions were made based on a helical acquisition at 120 kV tube voltage acquisition and a modulated tube currentexposure time (mAs), derived from the anterio-posterior and lateral scout scans. Radiation dose-length products were collected from the RDSRs and converted to patient ED. The CT image reconstructions were performed at 0.75mm slice thickness and di-mension of the reconstructed ROI image was 37x37cm in the axial plane, in craniacaudal length direction covering the whole instrumented spine, (Figure 2).

Data Analysis

The CBCT and CT images were reviewed on a PACS system with 3D volumes displayed in a multi-planar format. The window width and level were set to optimize visualization. Screw position assessments were performed using the Gertzbein grading [13]:

• grade 0 (screw within the pedicle without cortical breach)

• grade 1 (0–2 mm breach, minor perforation including cortical encroachment)

• grade 2 (2–4 mm breach, moderate breach)

• grade 3 (more than 4 mm breach, severe misplacement).

Each screw was assigned a grade from 0 to 3, for each imaging modality. Consequently, a 4x4 contingency table to compare the similarity in rating was created. (Figure 3) illustrates an example of each of the 4 grades on both CBCT and CT from the diagonal of the contingency table (i.e. agreement between both imaging modality for each grade). All images in (Figure 3) were displayed for comparison at equal display settings optimized for bone and hardware imaging. Grades 0 and 1 were considered clinically accurate, whereas grades 2 and 3 were considered misplaced.

Figure 3:Images displaying all the 4 grades from CBCT and CT for the same screw. The chosen screws for each grade have agreement between both imaging modalities.

Statistical Analysis

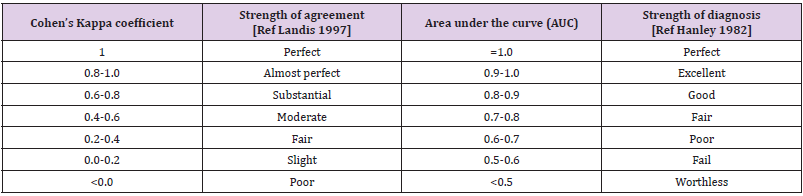

Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (κ) was calculated to assess the agreement between CBCT and CT based on the contingency tables and was classified according to Landis et al. [14] as detailed in (Table 1). Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of misplaced screws detected on CBCT which were confirmed as such on CT; whereas specificity was defined as the proportion of screws accurately placed according to CBCT which was confirmed as such on CT. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed and area under the empirical and fitted ROC curves (AUC) were computed to assess performance of CBCT as a diagnostic tool whose performance was classified according to Hanley et al. [15] (Table 1). Two-sided Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used for comparison where appropriate. Two-sided AUC comparison test was performed. Confidence Intervals (CI) were computed at 95% and expressed between brackets. A p-value (p) less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Table 1: Relation between Cohen’s Kappa coefficient and strength of intermodality agreement as well as relation between area under the receiver operating characteristic curve value and strength of diagnosis.

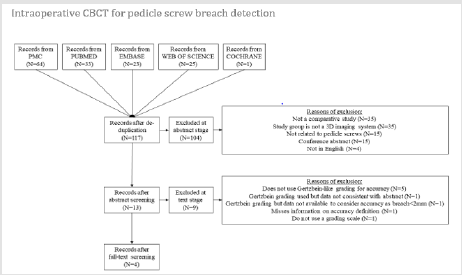

Literature Review

A systematic review was conducted in order to perform a proper comparison with all the existing literature on assessing the diagnostic performance of intraoperative 3D imaging versus CT. The review was performed using PubMed Central, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane with the following search strategy: (“pedicle screw placement” AND “sensitivity” AND “specificity” AND “imaging”). After filtering for duplicates from the various search engines, 5 exclusion criteria were applied during abstract screening: (a) articles not written in English, (b) conference abstracts, (c) articles that do not report about pedicle screw (e.g. sacroiliac screws), (d) articles that are not comparative studies, and (e) studies that do not consider an intraoperative 3D system as study group (e.g. 2D radiography, electromyography, etc.). After text screening, papers that did not report clinical accuracy for screw placement by using a Gertzbein-like grading i.e. (2-mm increment scale relative to breach) were excluded as also data with inconsistency or missing in-formation. All preclinical and clinical studies were included. Literature data with available contingency tables, or with detailed numbers of screws per grade for each group from which contingency tables could be generated, were used to calculate sensitivity, specificity, and AUC and statistical tests performed to ensure a fair diagnostic performance comparison between all studies.

Results

Two hundred forty-one cannulated pedicle screws were placed percutaneously: 3 (1%), 168 (70%), and 70 (29%) in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine respectively.

Accuracy Comparison Between CBCT and CT

All cadavers had their full instrumented spine imaged with 3 CBCT as seen in comparison with CT, (Figure 2). Table 2 corresponds to the contingency table comparing the grading assessment between both imaging modalities for each screw. Out of the 241 placed screws, 134, 22, 6, and 17 screws were rated by both imaging modalities as grade 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively: yielding a total of 179 screws with equal ratings. With respect to screws considered as accurate placement on CT, twenty-four screws and one screw were rated as grade 1 and 2 respectively on CBCT while they were rated grade 0 on CT, whereas thirteen screws and three screws were rated as grade 0 and 2 respectively on CBCT while they were rated as grade 1 on CT. With respect to screws considered as misplaced on CT, two screws were rated grade 0 and three screws were graded 1 on CBCT while they were rated as grade 2 on CT. Finally, two and twelve screws were rated as grade 1 and 2 on CBCT while they were rated as grade 3 on CT. The Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was κ=0.84 [0.75-0.93] indicating almost perfect agreement in assessing accuracy between CBCT and CT.

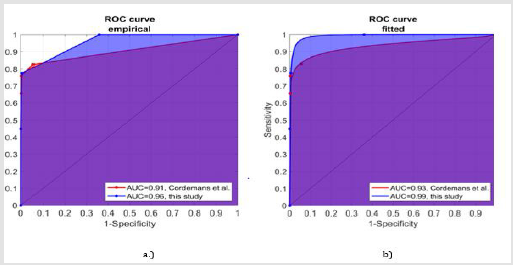

The agreement in the lumbar spine was almost perfect (κ=0.87 [0.70-1.00]) as well as in the thoracic spine (κ=0.83 [0.59-0.82]). The sensitivity and specificity of CBCT were 0.84 [0.70-0.93] and 0.98 [0.95-0.99], respectively. Sensitivity and specificity in the lumbar spine (0.89 [0.52-1.00] and 0.98 [0.91-1.00]) were higher than in the thoracic spine (0.83 [0.66-0.93] and 0.98 [0.94-1.00]) but not statistically different (p=1 for both). The AUC derived from the empirical and fitted ROC curves were 0.95 [0.91-1.00] and 0.96 [0.92-1.00], respectively; indicating CBCT to be an excellent diagnostic tool for pedicle screw placement compared to CT.

Radiation Dose of the Subjects

The patient ED in CBCT imaging was significantly lower than CT for all 7 cadavers (median 8.2 mSv vs 12.9 mSv, p<0.05). The average ED was 7.2±5.4 mSv in CBCT vs 14.3±3.4 mSv in CT with a 53% ED reduction on CBCT.

Literature Review and Comparison

The initial database search identified 117 studies without any duplicates. 104 articles were excluded after scrutiny of abstracts. The two most common reasons for exclusion were articles not being comparative studies (n=35) and the study group not corresponding to an intraoperative 3D imaging such as 2D radiography, EMG, or other techniques (n=35). Fifteen studies were not related to pedicle screws (e.g. iliac screws), and an equal amount corresponded to conference abstracts. Four abstracts corresponded to papers not written in English. From the remaining 13 articles, 5 other exclusions were applied at text screening level. The most common reason of exclusion was not using a Gertzbein-like grading with 2 mm increment for breach (n=5) [16-20]. One study was excluded because of inconsistency between the data in the abstract and in the text [21]. One study did not use a grading scale but revision surgery as surrogate parameter for screw misplacement [22].

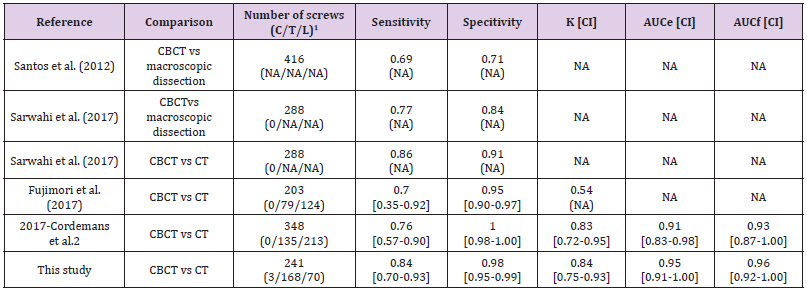

Another study did not confirm whether the obtained accuracy was indeed breach < 2mm or all breaches (i.e. grades 1, 2 and 3) [23]. One study did not provide enough information to compute accuracy for breach <2mm and considered all breaches as misplaced screws [24]. Finally, there were 4 studies that were discussed in this review [25-28], (Figure 4). Two cadaveric studies compared intraoperative CBCT vs macroscopic dissection [25,26]. In one study results were compared to CT as well [26]. Two clinical studies compared CBCT vs CT [27,28]. Details are presented in Table 3, showing sensitivity, specificity, and AUC where applicable. Sensitivity and specificity in literature ranged between 0.69-0.86 and between 0.71-1.00, respectively. The AUC could only be derived from one study [28] with an available contingency table yielding AUC from the empirical and fitted ROC curves of 0.91 [0.83-0.98] and 0.93 [0.87-1.00] respectively. Figure 5 shows a comparison of the ROC curves and corresponding AUC.

Table 3: Literature data comparison. C, T, and L correspond to cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal levels, respectively. Κ corresponds to Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. AUCe and AUCf correspond to the area under the empirical and fitted receiver operating characteristic curve, respectively. NA indicates not available data.

Note: CI: confidence interval; K: Kappa

CBCT: cone beam computed tomography; CT computed tomography.

Figure 5: Comparison of the ROC curves and the corresponding AUC. (a) Comparison of empirical ROC curves of Cordemans et. al. and this study; (b) Comparison of fitted ROC curves of Cordemans et. al. and this study.

Discussion

Hybrid ORs support multidisciplinary use of 2D and 3D imaging and navigation for open and minimal invasive procedures [10]. This cadaver study sought to assess the diagnostic performance of CBCT from a C-arm within a hybrid OR compared to diagnostic CT. Unlike mobile C-arm with CBCT capability and mobile CT, the C-arm system in the hybrid OR has an image acquisition and processing chain comparable to diagnostic CT scanners, enabling better management of image quality and radiation dose exposure [29]. While macroscopic dissection is the gold reference for evaluating pedicle screw placement, CT is the clinically viable alternative [26]. Choosing a cadaver study over a clinical study allowed for immediate comparison between CBCT and CT. Furthermore, cadaver studies allow uniformity of CT and CBCT protocols on the same scanner to ensure fair comparisons. In clinical studies, follow-up scans are often performed several months after surgery. Bone remodeling and regrowth or screw loosening occurs during the follow-up period which can influence the Gertzbein grading introducing thus possibilities for comparison errors.

The almost perfect inter-modality agreement of this study was suggestive of CBCT as a viable replacement for postoperative CT. The sensitivity obtained for the CBCT images was 0.84, indicating that 84% of misplaced screws detected on CT, were detected on CBCT. Of the 7 screws that were missed as a misplaced screw in CBCT, 6 were in the thoracic region. A specificity of 0.98, indicates in 2% of the cases, CBCT identified screws as misplaced when they are assessed to be well placed on CT. The screws that had the degree of cortical wall penetration overestimated in the CBCT, were mainly in the thoracic region. Interestingly, 5 of 7 screws were missed as misplaced on CBCT and 3 of 4 instances where the screw was labelled as misplaced on CBCT but a well-placed screw on CT, had a difference of 1 grade. In Gertzbein, there is an increment of 2mm in the amount of dis-placement between the consecutive grades. It is likely that the metal artefacts and the small pedicle sizes in the thoracic region, could potentially be the cause for the 2mm error in the assessment. A higher sensitivity compared to specificity suggests that CBCT based assessment tends to underestimate pedicle breaches compared to CT. Clinically, it is important to detect a truly misplaced screw.

Therefore, sensitivity is the most important parameter. However, sensitivity and specificity should both be compared together to get the overall picture. AUC analysis from ROC curves is the radiologically accepted technique to assess a system’s diagnostic performance described by a single number, as it considers sensitivity-specificity for all grades. The CBCT used in this study yielded AUCs suggestive of its excellence as a diagnostic tool for assessing screw placement during surgery. The conducted systematic literature review yielded 4 studies meeting the search criteria. The sensitivity and specificity of this study was in the upper range from the reported values in the literature, (Table 3). The Cohen’s Kappa and the AUC are indicators of the strength of agreement and diagnosis comparisons respectively. The strength of agreement was superior to the study performed with a mobile CBCT by Fujimori et al. [27] and comparable to a study performed with CBCT in a hybrid OR [28]. The study by Cordemans et al. is the only study from which the AUC could be derived for comparison of diagnostic strength [28].

These values were lower than in this current study but not statistically significant (p=0.20 and p=0.27 for the empirical and fitted AUC, respectively). The fitted AUC accounts for the continuous nature of measuring breach while the em-pirical AUC only takes the 2mm increment as defined by Gertzbein. Inclusion of a high number of misplaced screws (18% with a grade 2 or higher breach as per Gertzbein) and screws in the cervical or upper thoracic regions where the pedicle sizes are small (36% screws were in these regions) provide a better evaluation of the technology. This is reflected by the higher confidence interval compared to literature, thereby providing a higher reliability of sensitivity. The CBCT offers significant patient ED reduction (53% reduction) compared to CT. In institutions where a threshold for patient radiation dose exposure exists for perioperative procedures, one can justify the use of intraoperative CBCT as a diagnostic tool at a lower radiation dose exposure compared to CT, without altering diagnostic judgement of screw placement.

Cervical screws were limited in this study and detection of pedicle breach in the cervical region may be more challenging, given the smaller pedicle diameter and the shoulder superimposition in the image. Additional studies addressing other factors impacting image quality such as contrast-to-noise ratio, severity of metal artefacts, image reconstruction algorithm, and radiation dose protocol should be performed to complete the diagnostic evaluation of CBCT versus CT.

Conclusion

Intraoperative CBCT by C-arm in a hybrid OR is highly reliable

in identification of screw placement at significant dose reduction.

A systematic literature search demonstrated superior performance

compared to the existing CBCT of mobile C-arm systems confirming

reported performance by another study using a hybrid OR system.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.