Nutritional Therapies for Patients with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review

Introduction

Physical disability (PD) is the impairment of the locomotor system, which includes the Osteoarticular, Muscular and Nervous systems. Diseases or injuries affecting any of these systems, either independently or altogether, can cause physical limitations in degrees and severities that can vary, depending on the affected body segments and the type of injury. Presenting themselves in the form of paraplegia, paraparesis, tetraplegia, tetraparesis, ostomy, amputation or absence of limb, cerebral palsy, limbs with congenital or acquired deformity, except aesthetic deformities and those that do not causes difficulties for the performance of functions [1- 3]. This theme conjectures different types of discussions, among them aspects of the field of nutrition, in which a series of changes related to the difficulty of chewing and swallowing, loss of appetite caused by pain or medication, immobility that restricts being able to go shopping and preparing meals, changes in body composition and inadequate nutritional status [4,5]. In addition, it is noted that people with PD tend to adopt sedentary lifestyle (LS), with significant reductions in the level of daily physical activity, which negatively affect various aspects of health, quality of life and life expectancy. The motor limitation resulting from the deficiency, promotes a reduction in lean mass and a decrease in the basal metabolic rate, which may reach 30%, characterizing the outcome of obesity [6,7].

From this perspective, many people with PD begin to exercise, enter sports programs, and often become athletes. In this manner, they include an adequate food plan in addition to physical activity in order to minimize the consequences of the trauma and the risk of developing associated diseases [8]. In regards to adequate nutritional therapies, it is perceived that they are fundamental to maintain the proper functioning of the organism, insofar as some eating problems are most commonly found as low weight, overweight/ obesity, constipation, swallowing problems/dysphagia, drug/ food interactions. The seriousness of these conditions depends on several individual factors (age, level of motor dysfunction, severity of disability, health in general), environmental and socioeconomic conditions [9-11]. Thus, the objective of the present study is to carry out a systematic review of the production of knowledge that demonstrates nutritional therapies from food or supplementation and its effects on the health of people with PD.

Methodology

Research Strategy and Selection of Studies

This systematic review (RS) was performed in the following databases: PubMed and Scopus between 2012 and 2021. The descriptors derived from the MeSH Terms used were diet, nutrition therapy and disabled persons. Based on the descriptors and Boolean operators, the following search strategy was performed diet* OR nutrition therapy AND disabled persons, continuing in this manner in all searched databases. The bibliographic references of the included articles were also searched. Two reviewers independently analyzed the studies. An initial evaluation was carried out, based on the titles and the abstract of the articles, rejecting those that did not meet the inclusion criteria or presented some of the exclusion criteria. When it was unclear whether the eligibility criteria were met, a third reviewer reviewed the full text.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Original articles with a cross-sectional, longitudinal, descriptive and interventional design were included, which addressed nutritional therapies, either by food or supplements, in people with PD, in the adult phase (20 to 59 years old), of both genders, published in the period from 2012 to 2021, in the English language. We excluded articles with:

1) Studies on animals,

2) Studies examining another type of population,

3) Intellectual or mental disability, and

4) Studies in which only nutrient serum analysis was performed.

Evaluation of the Quality of the Studies

All the included studies were critically evaluated using the Downs & Black checklist (1998) , and in order to follow the requirements determined for the elaboration of a systematic review, it was used as reference the checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) [12,13].

Data Abstraction

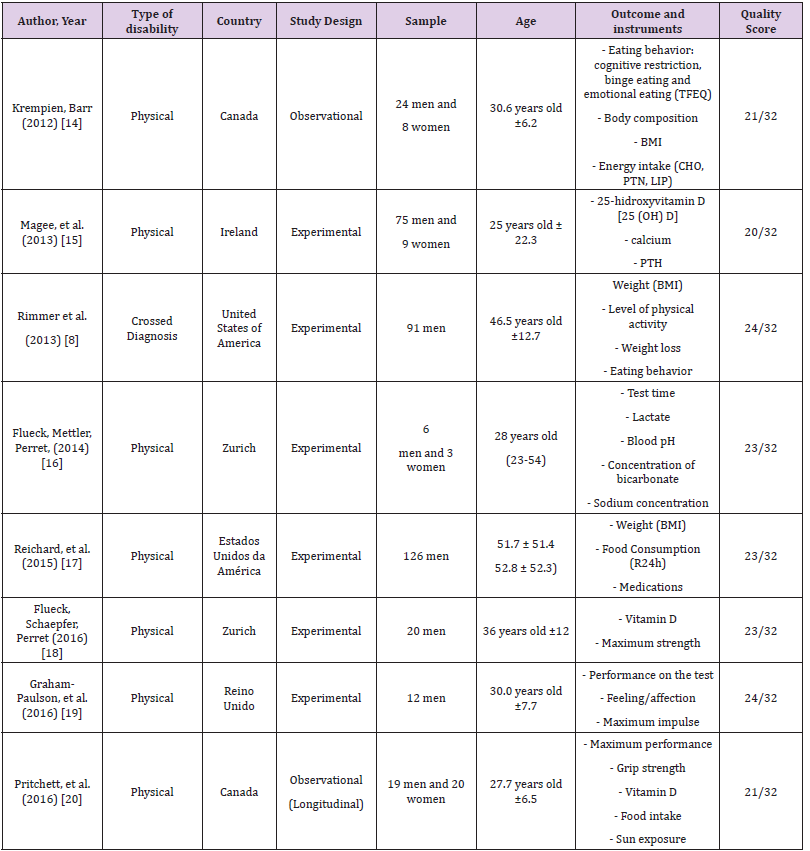

Two evaluators (JCAM and MCSM) independently extracted data on the characteristics of the study (year of publication, country of origin, type of disability and study design), subjects (gender and age) and which evaluation or intervention was performed in patients with PD (Table 1). The outcome of interest were the effects of nutritional therapies on the health of patients with PD.

Note: TFEQ: Three Factors Eating Questionnaire; PTH: Plasma Parathyroid Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index; CHO: Carbohydrate; PTN: Protein; LIP: Lipíds; pH: Potential of Hydrogen; WHR: WAIST-TO-HIP RATIO

Results

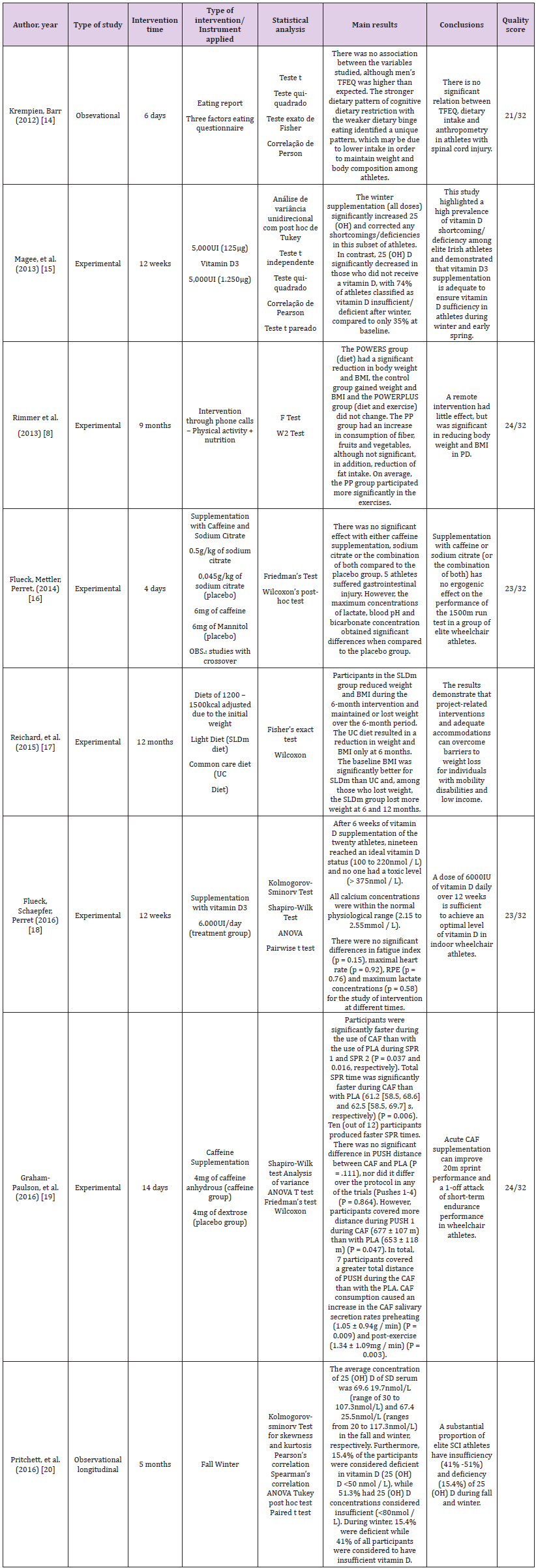

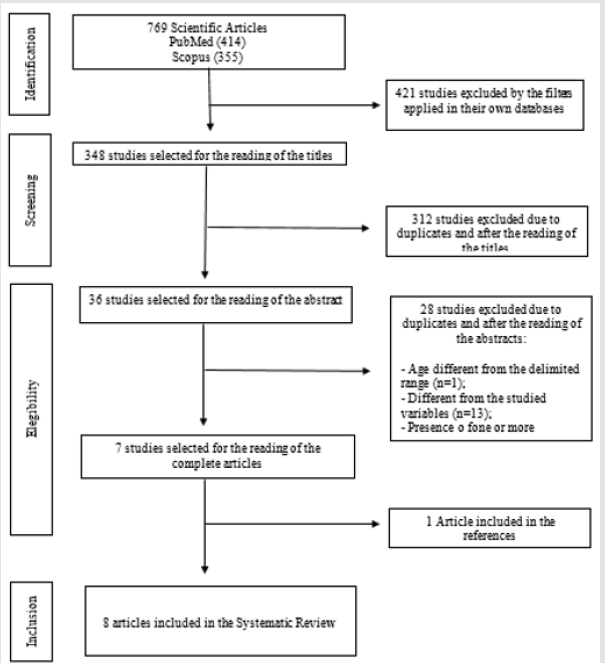

The search strategy described identified in the first search 769 articles in the following databases: PubMed n=414 (53,83%) and Scopus n=355 (46,17%). Then, the filters applied at each base excluded 421 articles. In the third step, 312 articles were excluded due to duplicates and after reading the title and the abstract, remaining 7 articles for a full-text reading, with inclusion of another article from the references, thus, 8 articles were included in the SR (Figure 1). Of the eight articles reviewed, two were conducted in the United States, two in Switzerland, two in Canada, one in Ireland and one in the United Kingdom. The study sample ranged from 9 to 126 people of both sexes, with ages ranging from 23 to 46.5 years old. The studies included subjects with a single diagnosis of motor dysfunction, while the others included multiple diagnoses, such as tetraplegia, paraplegia, multiple sclerosis, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, stroke, rheumatoid arthritis and osteogenesis imperfecta. Among the articles studied, six were experimental and two observational. Study participants were recruited through clinical rehabilitation facilities, hospitals, clinics, medical offices, Paralympic programs, wheelchair rugby players and sports medicine team. Although it was not in the inclusion criteria that the participants of the studies had to be athletes with PD, the samples counted on this group of people. The study approaches were predominantly interventions with educational activities, with emphasis on participants’ knowledge about nutrition, as well as their eating behavior from food surveys (food register, 24 hour food recall (R24h). One of the studies worked with different interventions (diet with exercise or diet only) through telephone contact, focusing on food and nutritional education through educational activities, nutritional counseling of individuals; other studies have included dietary supplementation, observing its effect on weight loss, vitamin D levels and arm-grip strength (Table 2).

Discussion

Based on the articles included in this SR, it was observed that research on nutritional therapies or interventions in relation to the population with PD occurs mainly with elite athletes, resulting from vitamin D3, caffeine and sodium citrate supplementation. Articles related to eating behavior were also found in three aspects: cognitive restriction, lack of food and emotional eating, as well as the awareness of the participants in regards to food. The articles showed that vitamin D supplementation increased their serum levels; the diet program, exercise, education and monthly counseling with trained professionals led to weight loss, and a proper diet under the recommendation of health professionals improved the nutritional status in adults with PD.

Vitamin D and Physical Disability

Vitamin D is primarily attributed the role of important regulator of osteomineral physiology, especially of calcium metabolism. Currently, vitamin D is considered a prohormone steroid, being present in foods and vitamin supplements in its two molecular forms: vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol), vegetable origin, and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), animal origin [14-16]. The daily-recommended intake for bone health maintenance is 600 international units (IU) for people between 1 and 70 years old (including pregnant and lactating women). After sun exposure, cutaneous synthesis accounts for 80% of the source of this micronutrient, the remainder being obtained through foods rich in vitamin D, such as fish, eggs and dairy products [17]. The importance of vitamin D in the homeostasis of the organism has aroused great interest in the scientific community, evidenced by the expressive number of studies produced in these last decades. In this sense, a series of epidemiological evaluations show that a significant portion of the world population, regardless of age, ethnicity and geographical location, has low levels of vitamin D [15]. In this sense, the risk factors for hypovitaminosis D include low sun exposure (high latitudes, cold seasons of the year and use of sunscreens), dark skin, obesity, smoking habits, malabsorption syndromes, liver diseases or nephropathies, advanced age and institutionalization [18]. The importance of this vitamin is not only associated with bone health, but also on physical performance and injury prevention in individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) and their levels may be deficient or insufficient due to inadequate diet, anti-convulsive medications, reduced exposure to sunlight, limited functional mobility, impaired thermoregulation, amount of exposed skin, season of the year and latitude [19]. Regarding studies with vitamin D supplementation, doses ranged from 5,000IU/day to 50,000IU. Moreover, the 12-week period is already effective for these levels to be adequate. It is relevant to note that there are no specific recommendations for vitamin D for people with PD. Moreover, since these recommendations exist for those without PD, in Brazil, government recommendations are still very conservative for the maximum limit of supplementation allowed to nutritionists, since doses higher than 800IU/day are only through medical prescription [20-22]. Thus, the need for supplementation of this vitamin needs to be considered from a variety of perspectives, especially in clinical practice, in which the maximum amount of supplementation allowed to nutritionists has not been shown to promote significant changes in insufficient or deficient serum levels of vitamin D and on the consequent changes in health-related outcomes [20-22].

Ergogenic (Caffeine and Sodium Citrate) and Physical Disability

Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) is one of the oldest and most used substances in the world with the objective of increasing physical and mental potency. In the last decades, its use for stimulating effects has increased considerably in the sports environment, with the intention of enhancing performance due to studies on its ergogenic effects [23,24]. It can be classified as a pharmacological ergogenic, but it can also be considered a nutritional ergogenic, as it is usually found in some products such as teas, coffee, cocoa, guaraná, chocolate and soft drinks, as well as medications [25]. It is considered a non-essential nutrient, in which the effects on our body include: Central Nervous System stimulation, diuresis, lipolysis and gastric acid secretion [26,27]. It is a substance rapidly absorbed by the intestine, reaching its maximum concentration in the bloodstream between 15 and 120 minutes after its ingestion. Its action can reach all the tissues, since its transport is done via bloodstream, being later degraded by the liver and excreted by the urine in the form of coproducts. Although only a small amount of caffeine is excreted (0.5 to 3%) with no change in its chemical constitution, its detection in the urine is relatively easy [28]. In addition, it can be seen in the studies carried out with the use of caffeine that this supplementation is applied most often with athletes who make constant use of ergogenic resources. Moreover, in one of the studies, supplementation with this substance did not reach its ergogenic effect, which is still quite controversial, since apparently other mechanisms may be associated with its action, improving performance in different types of exercise [26,29].

Eating Behavior and Physical Disability

Besides being complex, eating behavior is influenced by several cultural, social, psychological, physiological and nutritional factors, which are characterized by two main functions: maintaining the quantity of nutrients necessary for our survival (physiological processes) and the pleasure that the act of eating provides us, releasing neurotransmitters (serotonin and dopamine) responsible for pleasure and well-being [30]. It is noticed that eating behavior has been theme of several studies over time, as well as it is a factor of interest of people who have PD. Although it is known that other factors permeate the issues involving consumption and eating habits of these individuals such as, lack of financial resources for healthy food, modified lifestyle, mobility to prepare meals, drug nutrient interaction, associated diseases, etc. [31,32]. In this sense, the increase in weight observed in the world population, as a result of abundance and easy access to food in modern societies, can cause behavioral changes described under the name of cognitive restriction, which consists of a mental position adopted by the individual in relation to food, with the objective to reduce energy intake that leads to a restrictive eating behavior [33]. This behavior can often present a paradoxical phenomenon. While under normal circumstances, individuals with cognitive impairment tend to limit food intake quantitatively and qualitatively, many of them, when exposed to certain situations, tend to overeat [34]. What is observed with the studies that approach this subject is that to these factors linked to the eating behavior although they show that when there is greater dietary restriction, smaller is the energetic intake. This fact is based on the population of the study being athletes with PD and that have a greater concern with aspects related to the body, and this may be a reality of our society and specific to the population of physically disabled individuals [31].

Weight Loss and Physical Disability

Individuals with PD often adopt sedentary lifestyle, with significant reductions in daily physical activity, which negatively affect various aspects of health, lifestyle and life expectancy. The motor limitation resulting from the disability promotes a reduction in lean mass and a decrease in the basal metabolic rate that can reach 30%, resulting in obesity [6,35]. This increase in health risk factors related to the high prevalence of obesity has been closely related to changes in lifestyle of the individuals, especially in relation to eating habits and habitual physical activity, associated with overweight and obesity, which is an important factor in determining health [36]. Obesity is a chronic multifactorial disease, characterized by the accumulation of body fat resulting from prolonged energy imbalance, which may be caused by excessive consumption of calories and/or physical inactivity. This fact, as a rule, causes changes in body composition, mainly loss of lean mass and consequently decrease in the rate of basal metabolism and daily energy expenditure [37,38]. For this reason, proper nutrition is one of the keys to good health performance. Nutritional care in people with PD should be emphatic because they are more susceptible to osteoporosis, renal lithiasis, altered metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and lipids. Additionally, they are more likely to develop cardiovascular diseases [39-41]. In addition to unbalanced diet, people with PD such as spinal cord injury usually reduce drastically the levels of physical activity, with a positive caloric balance (reduced activity and increased and incorrect dietary intake) aimed at accumulation of energetic stock, with consequent adipocitary hypertrophy and accumulation of this tissue in the abdominal/ visceral region [8].

In this sense, the studies show that interventions for weight loss for a period of 12 weeks are already effective regardless of the economic conditions of the population. Besides, it demonstrates that the incentive to diet modifications and the practice of physical activity can be allied to weight control and that food and nutrition education emerges in this theme as a way to guide this population in improving their quality of life and eating aspects [8,40]. Regarding the evaluation of the quality of the studies included in this SR, eight of them presented a score higher than 60% of the maximum score given by the Downs & Black scale, which indicates a good methodological quality, with well-conducted studies and results relevant to dietary conducts in people with physical disabilities.

Limitations

The studies analyzed are not subject to limitations, especially regarding the difficulty in finding studies with people with PD who were not athletes, because it is important to point out that the effects attributed to each nutritional therapy may be different based on this population. The difficulties related to the studies were based on the adherence of the participants, mainly in the interventions for the proposed period, besides those that were not performed in a randomized and placebo controlled manner. It is essential to point out that the process of search of this review was carried out following all methodological procedures in order to ensure its quality.

In this sense, it is suggested future studies that take into account longer-term interventions, a greater number of individuals and even with non-athlete PD population in order to have a greater delineation on the therapies used in these people and what are the benefits and adverse effects of interventions.

Conclusion

The studies analyzed showed that vitamin D supplementation increased their serum levels; supplementation with caffeine and sodium citrate still needs further studies, since only one intervention had a satisfactory result, with an ergogenic effect of this substance; a weight loss program combined with nutritional counseling based on eating and nutritional education reduced weight, BMI and provided an improvement in lifestyle. The evaluation in regards to eating behavior is important, mainly in face of bodily distortions evidenced in the current conjuncture. Thus, it is possible to understand that adequate nutritional therapies are efficient in improving the health of people with physical disabilities, however, it is necessary that more studies be carried out to recommend therapies, anthropometric measures individualized for these patients and that fulfill this nutritional deficiency in order to improve their quality of life.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.