Parenteral Vs Enteral Nutrition as an Improvement in Wound Healing in the Severely Burned Patient in the ICU

Introduction

Burns are defined as injuries produced in living tissues, due to the action of various physical agents (flames, hot liquids and objects, radiation, electric current, cold), chemical (caustic) and biological, which cause alterations ranging from a simple erythema until the total destruction of the structures [1]. Severe burn induces the patient to severe oxidative stress, a systemic inflammatory response, increased and persistent hypermetabolism and hyper catabolism with secondary sarcopenia, as well as organic dysfunction, causing sepsis, increasing mortality and energy deficit, the negative balance of proteins, antioxidant micronutrient deficiency during thermal stress giving poor clinical results [2]. Those with relevant criteria such as a severity index greater than seventy points, or with second or third degree burns as a whole, with greater than twenty percent of the total burned body surface (STCQ), patients under two years of age, or adults over sixty-five years of age with ten percent or more second or third degree burns, as well as all patients with respiratory or smoke inhalation burns, high voltage electrical burns, burns associated with multiple trauma and burns with associated serious diseases [3]. Therefore, the metabolic consequences of burns (especially those that exceed 20%- 30% of the STCQ), constitute a permanent challenge for those involved in the treatment of these, in their desire to achieve a prolonged survival, the successful rooting of the grafts, and adequate rates of tissue repair and healing [4].

The hypermetabolism that occurs due to the burn is immediate: increased susceptibility to infection, development of sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction, poor wound healing, loss of placed grafts, and eventual death; adding insufficient intake of energy, nitrogen, and micronutrients [4]. Caloric demands in critical condition are very high, assuming that it is accompanied by a large increase in basal metabolic output, that is, that the critically ill patient is strongly hypermetabolic. Therefore, when patients in a state of serious stress due to trauma, sepsis, burns or critical illness, they exhibit an accelerated catabolism of body proteins, and an increase in the degradation and trans nomination of branched chain amino acids in the skeletal muscle, with the consequent increase in the generation of lactate, alanine and glutamine, and a large flow of these substrates between the muscle (periphery) and the liver (central organ). The metabolic consequence is a marked elevation of glucose production in the liver, a process called gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenesis prevents the accumulation of endogenous substrates from catabolism, which have no other way of purification. It also makes glucose available to those organs that depend on it for energy, such as the brain or bone marrow. Patients with severe sepsis, multiple trauma, or extensive burns require a higher protein intake of the order of 2.5 to 3.0 g / kg per day. So, when a burn occurs, gastric function is inhibited due to catabolism, since as mentioned above, it is necessary to have proteins and energy for the different organs of the patient’s system, and the absorption necessary to maintain an energy balance is deficient.

In the same way, during this process, they present hyper catabolism and hypermetabolism to compensate the hemodynamic state due to the increase in cardiac output, it is carried out by intestinal ischemia due to the burn, which affects the nutritional status of the patient and the healing of the wounds [1]. Also, the metabolism of PGQ can increase more than twice that of an unstressed subject and cause a significant depletion of lean body mass in the weeks following injury. Survivors may exhibit sequelae that will require prolonged specialized surgical treatments, therefore, the nutritional support in the PGQ acts by consuming the energy of the diet itself, avoiding hypermetabolism, ensuring the best response of the host to aggression, reducing the risk of complications, of skin grafts, the support of tissue repair and healing [4]; together with the shortening of the hospital stay and its impact on the Adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Consequently, the hypermetabolism observed after the burn is the result of the hormonal shift that under basal conditions would support the tissue deposition of substrates stimulated by the action of insulin, towards another that favors the mobilization and use of the stored substrates; and where anti-insulin hormones such as glucagon, cortisol and adrenaline participate. In this way, glycolysis and glucogenesis, fatty acid synthesis and deposition, and protein synthesis are inhibited; while glycogenolysis is activated, and gluconeogenesis in relation to muscle proteolysis [3].

On the other hand, it is important to mention that it has been shown that an accumulated caloric-protein debt throughout the stay in the ICU contributes to an increase in morbidity and mortality with a higher rate of infections, days of mechanical ventilation, as well as hospital stay. It has also been shown that one of the main consequences of poor nutrition is difficulty in healing due to the hypermetabolism that the critical patient presents at that time [4]. From the foregoing, it is concluded that nutritional disorders compromise wound healing and PGQ survival since there are decreased concentrations of minerals and trace elements in the blood of the burned patient, so nutritional therapy should be aimed at the replacement of the amounts lost as several weeks may elapse before serum concentrations of a particular micronutrient are restored to normal [4]. Therefore, the nutritional status of the patient has an important influence on the repair process, poor nutrition causes delays in healing. If the weight loss is above 30% of the appropriate weight, the deficiency of amino acids such as cystine and lysine will slow down the neovascularization process, the collagen synthesis process, and the final remodeling process [5]. The higher the percentage of total body surface area (SCT) affected, the greater the risk of developing systemic complications. In the case of patients who have complications due to an infectious process, they are exposed to the risk of sepsis and mortality, and it also causes local complications. Altered host defenses and devitalized tissue enhance bacterial invasion and growth.

The most frequent pathogens are streptococci and staphylococci during the first days and gram-negative bacteria after 5-7 days, although the flora is always mixed [5]. Among the main activities of the nursing professional in intensive care, feeding is a primary care. This is demonstrated in the mnemonic FAST HUG BID encompasses seven minimum aspects in critical patient care (diet, analgesia, sedation, thrombus prophylaxis, elevation of the head, prevention of stress ulcers and glucose control) [6]. Its compliance shows the improvement in the patient’s prognosis [6]. One of the nutritional therapies used in critically ill patients is enteral nutrition (EN), which is a nutritional support technique that consists of administering nutrients directly into the gastrointestinal tract through a tube; and parenteral nutrition (PN), which consists of administering nutrients to the body by venous and extradigestive routes [6], through specific catheters, to meet metabolic requirements [7]. EN is indicated when the patient in all cases in which the patient requires individualized nutritional support and does not ingest the necessary nutrients to meet their requirements [7]. On the other hand, PN is indicated when the needs are greatly increased and the patient is not able to cover them with the intake, when the patient does not tolerate the intake due to hemodynamic alterations such as heart or respiratory diseases such as bronchial dysplasia. Similarly, in patients who are unable to swallow due to oropharyngeal disorders, to take special foods with a bad taste and essential such as amino acid diseases or who cannot have prolonged fasting times: glycogenosis, alterations in the oxidation of fatty acids [7].

Having a contraindication in patients with intestinal obstruction [7]. The latter is used in patients with alterations in the gastrointestinal tract, being in many cases the only way to provide nutritional support, it is indicated in patients whose gastrointestinal tract is not usable for the administration, digestion, or absorption of nutrients, for a period greater than five days or when the gastrointestinal tract is usable, but it is desired to remain at rest for therapeutic reasons [8]. However, it is also associated with metabolic, infectious, and mechanical complications, which increases mortality and deterioration in the quality of life of the PGQ [8]. Within its content, PN requires water (30 to 40 ml / kg / day), energy (30 to 35 kcal / kg / day, depending on energy expenditure: up to 45 kcal / kg / day in critically ill patients), amino acids (1 to 2 g / kg / day, depending on the degree of catabolism), essential fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals [9]. Usually 2 L / day of the standard solution is needed. Solutions can be modified based on laboratory results, by underlying disorders, hypermetabolism, or other factors [9].

Justification

Burns are considered a public health problem worldwide, causing approximately 180,000 deaths per year, mostly in lowand middle-income countries [10]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with the highest risk of exposure are usually women, however, the injury rate is relatively higher in men than in women [10]. In the United States in 2016, an estimated 500,000 people suffer from unintentional burns annually, 80% of them (40,000 people) require hospitalization [11]. According to data from the National Fire Protection Association during 2005, in the United States, 600,000 people were burned, of which 25,000 required hospital handling and 4,000 of them died [12]. At the national level, the National Epidemiological Surveillance System reported in 2011 that burns ranked 17th in frequency of new cases of disease with a total of 129,779 patients with burns, which generated an overall national incidence of 118.82 (113.25 in women and 124.61 in men). By age group, new cases were more frequent (in decreasing order): from 25 to 44 years (43,321 cases), from 1 to 4 years (13,864 cases) and from 20 to 24 years (13,816 cases) [12], while in 2013, 126,786 new burn cases were reported, and from January to June 2014, 65,182 cases. Of these burns, 56% occurred in adults between 20 and 50 years of age and 32% in children between 0 and 19 years of age. Similarly, 85% of burns in adults occurred while carrying out work activities, while burns in children occurred in 90% of cases, within their homes, of which 80% were due to hot water (eleven).

PGQ medical care is expensive due to pre-hospital and hospital expenses (including the costs of consumable biotechnology, paraclinical studies, drugs, nutrition, etc.), estimating costs per patient from 30 thousand to 499 999 pesos [12]. It has been observed that both types of nutrition are used for severely burned patients, however, it is necessary to determine the nutrition that contributes to healing, as well as the Knowledge Generation and Application Line (LGAC) that supports the Program. Educational “Care for the person in critical condition” which belongs to the Quality and Nursing Care Research Group [13]. The healing process is complex and multiple factors influence it, such as nutrition. Nutrition and healing are closely related, in this way specific nutritional deficiencies may cause a delay in the progression of healing [13]. When mentioning healing, it is very important to identify up to which layer of the skin is burned or damaged, in order to identify the healing time according to the nutrition administered. In the same way, it can be determined that according to the characteristics of the wounds, the time is determined, however the healing ranges from 4 to 12 weeks for their complete healing. The previous analysis determines the importance of basing the care of the PGQ in relation to parenteral vs enteral feeding in order to base the care provided by the nursing staff specialized in intensive care, to achieve wound healing in the shortest time possible, so as to avoid the morbidity and mortality of PGQ in the Adult Intensive Care Unit [14].

Objective

To compare whether parenteral vs enteral nutrition improves wound healing in the severely burned patient in the Adult Intensive Care Unit.

PICO

Description of the Problem

Due to the hemodynamic instability and the high demand for care it requires, the PGQ merits admission to the ICU. These patients present hyper catabolism and hypermetabolism to compensate for the hemodynamic status due to the increase in cardiac output due to intestinal ischemia due to the burn, which affects the nutritional status of the patient and the healing of the wounds. However, burns care is now being provided to an increasing number of older adults who may have nutritional deficiencies, such as wasting and sarcopenia. These nutritional disorders could compromise the healing of the wounds and the survival of the patient and delay the evolution and have a poor prognosis. On the other hand, there are different nutrients that are very important in the evolution of the burn patient, for example, glucose, is the most important source for the healing process, among other nutrients, which in the same way help the physiological system. Due to burns, there is a significant loss of body weight, mainly of lean mass, which is transferred to immune compromise, delayed wound healing, infection, sepsis, organ failure, and death. The healing process is complex and multiple factors influence it, such as nutrition. Nutrition and healing are closely linked, in this way specific nutritional deficiencies may cause a delay in the progression of healing.

Addressing wounds in a comprehensive manner is the role of nursing, which is why it is important to know the current approach to nutrition in the PGQ [13]. It is important to mention that in the PGQ the small intestine can present affectations due to the systemic response due to the burn, and therefore inhibits the digestion and absorption of the necessary nutrients for the patient and in turn decreases wound healing [11]. The extent of injuries, pain, involvement of other organs and systems in burn injuries (such as the airways and lungs, which in many cases would involve intubation and mechanical ventilation) could make the use of nutrition impossible enteral and require the placement of venous enteral accesses to supply the estimated amounts of nutrients improving wound healing Field code changed [15]. Therefore, the decision of what nutrition to have in the PGQ will be decisive for your improvement in the ICU.

Questions that can be Answered

1. What is the best adequate nutrition for the critically burned patient?

2. What is the incidence of the population to be big burned?

3. Why does parenteral nutrition best benefit a severe burn patient?

4. After how many hours, is it necessary to administer parenteral nutrition to the severely burned patient?

5. What impact does parenteral nutrition have on a severe burn patient?

6. What is the most important nursing activity in the nutrition of the great burn patient?

7. What benefits can parenteral nutrition bring to the severely burned patient?

8. What nutrients are the most important in a large burn patient on parenteral nutrition?

9. How is the epidemiology in the great burn patient and what is its incidence?

10. How important is parenteral nutrition in severe burn patients?

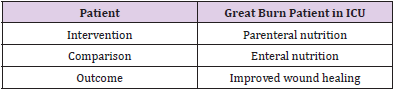

Analysis of The Question with Its Components

After analyzing the questions that could be answered, the one that best described the elements of interest of the present study was selected, which is presented in the following (Table 1).

Wording of the Question

Does parenteral nutrition compared to enteral nutrition improve wound healing in severe burn patients in ICU?

Search Methodology

Search Strategy

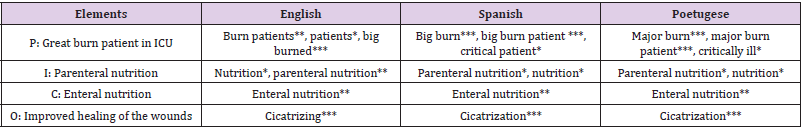

Regarding the search strategy, after having raised the problem and taking into consideration the elements of the PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome), the terms were identified and translated into a documentary language, adapting to the Health Sciences Descriptor (DeCS), the Medical Subject (MESH) as well as free terms, to have a controlled language for effective search (Table 2). These terms were raised in both English and Spanish and Portuguese. It is worth mentioning that the information search was carried out in two stages: the first, through databases of secondary sources (Cochrane and Tripdatabase) and the second stage in databases of primary sources such as the Virtual Health Library (VHL) portal, United States National Library of Medicine (PubMed), Elsevier, Redalyc, Lilacs and Medicine in Spanish (Medes). In the same way, the AND and NOT and limiters * and () were used as Boléan operators to obtain more specific results. Studies related to adults with severe burn injuries and nutritional therapy in patients with severe burn injuries, which have a preferential time of less than five years of publication, and in other options up to ten years old were considered according to their level of evidence and grade. recommendation.

Databases Queried

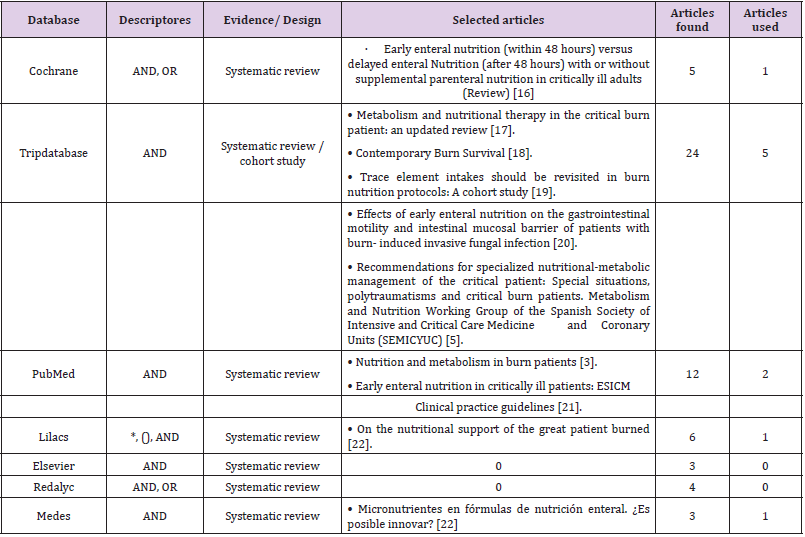

A query of information in databases was analyzed in the period from November 4, 2020 to February 22, 2021, 63 articles of interest were found in the databases, Cochrane, Tripdatabase PubMed, Redalyc, Lilacs, BVS, Elsevier and Medes. These articles were selected through critical reading to determine the level of evidence and grade of recommendation. With this, discarding all those that are not related to nutrition therapy in patients with great burns, obtaining a total of ten articles used [16-22]. To synthesize the evidence found, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) scale was used to assess and establish the grades of recommendation according to the level of evidence (Table 3).

Table 3: Translation of the question into documentary language.

Note: Evidence resulting from the query made in databases

Results

Relevant Studies

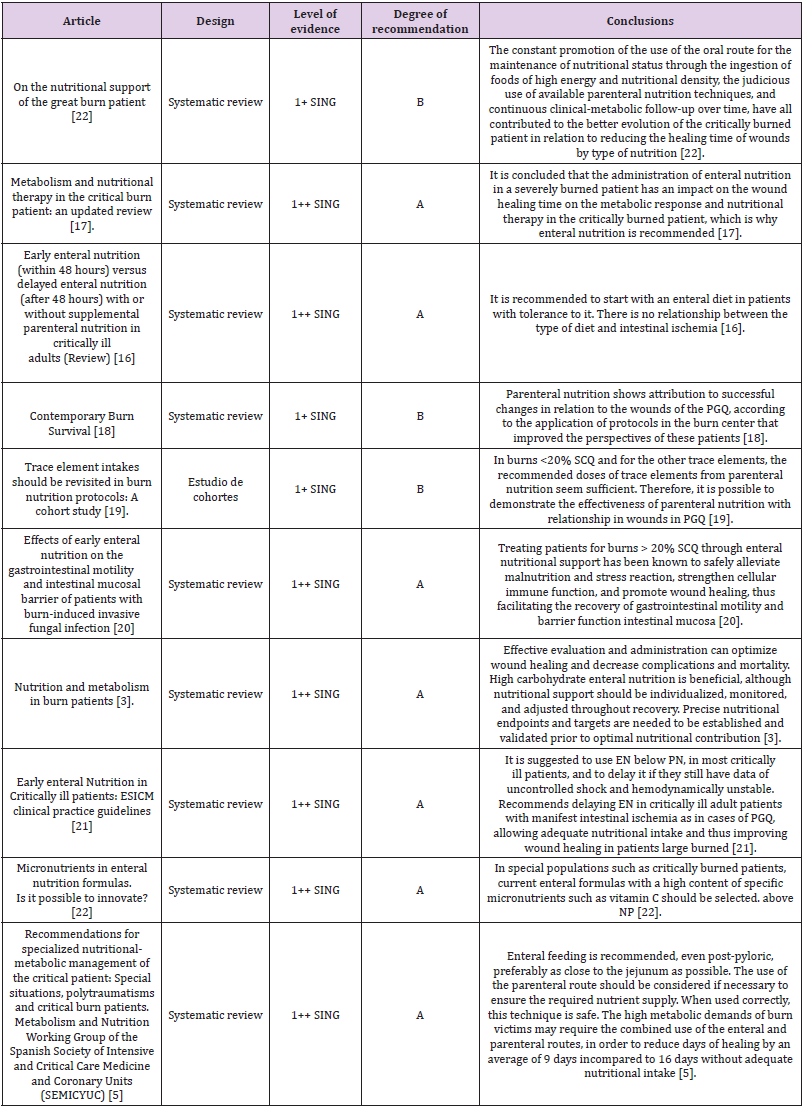

Of the 63 articles located with the aforementioned strategies, ten were used when meeting the desired criteria with the use of templates for the analysis of clinical trials and systematic reviews with the use of the “Critical Appraisal Skills Program” (CASPe) and with the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) scale to assess and establish the degrees of recommendation according to the level of evidence. Taking articles from systematic reviews and cohort studies, there are no experimental studies that verify the usefulness of both nutritional’s and the greater usefulness of either of these. The analysis of two out of ten articles determined that nutritional support is necessary as soon as resuscitation and resuscitation of the PGQ are completed, and hemodynamic stability and tissue perfusion are ensured [5]. The oral route should be preferred to feed the patient, the placement of naso enteral tubes could be necessary in many of them to avoid gaps in the provision of nutrients [17]. However, the dietary prescription could also be supplemented with energy-dense enteral nutrients in order to satisfy the high nutritional requirements found in the burn. Immunomodulation diets incorporating antioxidants, glutamine, and nucleotides have been described for use in nutritional support of burn injuries, but the results obtained with their administration have been mixed.

According to current knowledge, enteral nutrition is of choice; Likewise, during the resuscitation phase, the PGQ should receive high doses of vitamin C, as well as parenteral antioxidant cocktail supplements, which should be administered for variable periods of time according to the SCTQ [5]. Likewise, enteral glutamine intake seems to be a safe strategy capable of optimizing therapy, although more robust evidence is needed to support its use, thereby reducing healing times from nine days to 16 days on average [5].

Synthesis of the Evidence Found

Once the evidence was obtained from the articles, the conclusions about nutrition in the PGQ were compared.

On the other hand, it is based in a specific way on the methodological and design aspects, but not on the dimension of the perspective of suffering a disease or considering the economic implications of the recommended measures; situation that puts at risk the feasibility of its use in Latin American medical practice. Therefore, the articles are compared, as well as the conclusions obtained in each one of them (Table 4).

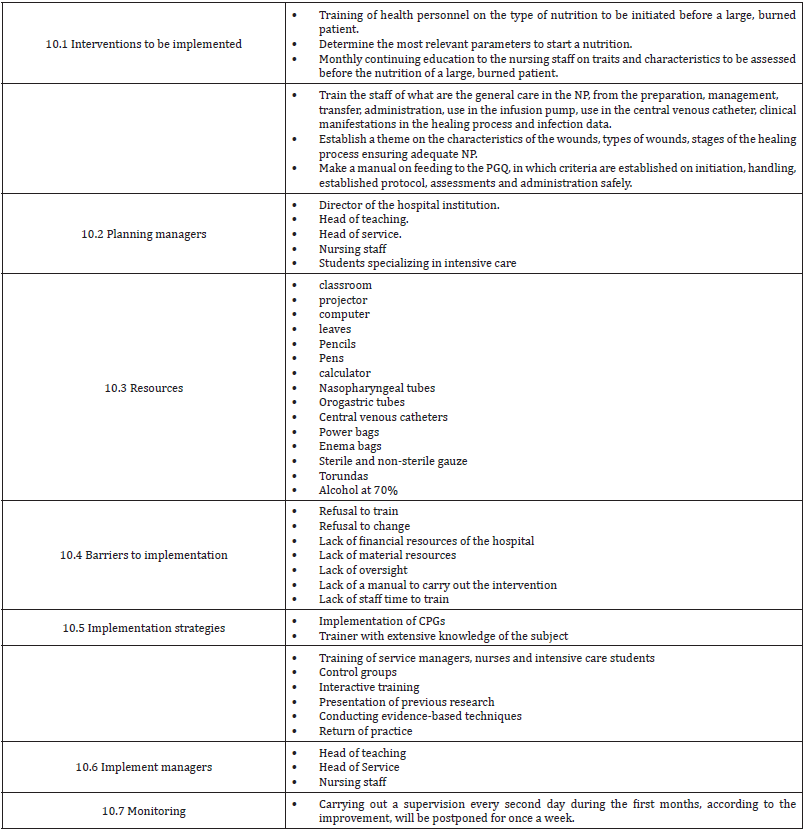

Implementation Plan

In this paragraph, note that it is a proposal by the authors for a possible implementation: The implementation of the research results is a long and complex process that requires effort on the part of all the agents involved, both patients, families, health professionals and the health system. Therefore, this section describes the necessary interventions to carry out (Table 5).

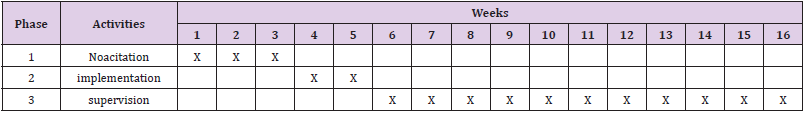

Schedule

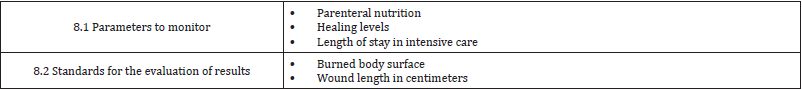

Evaluation Plan

Conclusion

Once the topic was finished, it has been possible to reach the conclusion that the nursing staff carries out, being fundamental in the clinical part about the type of nutrition applied to the great burn patient. The evidence shows that the type of diet to be applied to a PGQ is preferably NE over PN. Making a high caloric intake, supplementing with Vitamin C, Glutamine among other proteins. Parenteral nutrition is an option for severe burn patients with intestinal ischemia, although it is recommended to start with a bowel rest to prioritize EN. In case of not being able to provide enough caloric intake, supplement it with a parenteral diet, and in this way you would be having an adequate combination of both nutritional’s. Similarly, go to total parenteral nutrition, if and only if, the enteral option is not possible, as in the case of patients with burns in the face area or inhalation burns. Going to show that NE is effective in wound healing in PGQ, since it is dependent on the nutrients that can be provided, and not on the site or route that nutrition is administered.

Therefore, the following recommendations are analyzed:

• Identification of the PGQ with the characteristics according to the GPC.

• Monthly training of staff on the characteristics of wounds, stages, and processes of healing, and identify what type of nutrition is the most appropriate according to the framework established for staff.

• Design and / or implementation of research by nursing staff in relation to the nutrition of PGQ.

• Detection of intestinal ischemia.

• Nutritional rest of the patient until hemodynamically stable.

• Use of first choice NE.

• Use of complementary PN according to the characteristics of the patient.

• Use of total PN, only in cases of not being able to provide firstline enteral nutrition.

• Maintain the patient’s nutrition with high levels of glutamine in NE and PN, as well as other nutrients to be required to provide a positive metabolic effect in relation to wound healing. Therefore, it is suggested to carry out more studies in the field of nutrition in the burn patient, as well as more systematic reviews.

For more Articles on: https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.