Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects around 11% of the population over the age of 20 globally, with an increase in incidence in recent years [1]. Peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis and kidney transplantation are treatments that have been effective in increasing the life expectancy of people with CKD [1,2]. In the last three decades, the analysis of quality of life has been integrated as an indicator of the evolution of health status in patients with CKD to see beyond the number of years of survival. Quality of life is, according to the WHO, “the perception that an individual has of his place in existence, in the context of the culture and value system in which he lives and in relation to his objectives, his expectations, his norms, his concerns. It is a concept that is influenced by the physical health of the subject, their psychological state, their level of independence, their social relationships, as well as their relationship with the environment.” This concept encompasses objective and subjective aspects that reflect the degree of physical, emotional, social and economic well-being of each individual. The analysis of the quality of life in people with CKD allows us to understand the impact of the disease and its treatment, to know more about patients, how they evolve and how they adapt to organic alteration [3,4]. Currently, the analysis of quality of life in people with CKD seeks to generate evidence, qualitative and quantitative, to facilitate: the process of assessing human needs and the implementation of quality interventions in the care sectors [5]. In the health sciences, phenomenological research, and those with a qualitative approach in general, generate evidence that serves as a guide to practice sensitive to the realities of the people to whom care is directed, to their cultural diversity and to the contexts in which their lives unfold [6,7].

In studies related to quality of life in transplanted people and candidates for kidney transplantation, participants manifest as the main human responses: recurrent hospitalizations, uncertainty about the work situation, deterioration of body image, deterioration of sexual functionality, dependence on third parties, stress and guilt [2,8-12]. Specifically, people who are candidates for kidney transplantation manifest as the main human responses: anxiety and depression [13,14]. Transplanted individuals report acute rejections, medication side effects, and emotional instability; [12-15,16] immediately, after transplantation, they may perceive release with respect to dependence on renal replacement therapy, but as time goes by, they have to face various adaptation problems: side effects of medications, medical and social complications, among the latter the return to work, social and family life [12,16,17]. The analysis of quality of life, with its respective components and human responses in patients with a history of CKD is recent. Therefore, the needs inherent in the nursing care process may go unnoticed when directing care for people with these characteristics. Although there are numerous studies that quantitatively address health-related quality of life, [4,18,19] qualitative studies such as the present one provides particular evidence to integrate it into the holistic process of the nursing-patient relationship at different levels of care [13,20]. Therefore, the objective of this study is to analyze the perception of quality of life of people with kidney transplantation and kidney transplant candidates treated at the High Specialty Medical Unit of Mérida, to identify the related human responses through an interpretive phenomenological approach.

Design

A qualitative study was conducted with an interpretative phenomenological approach. From this design it is possible to reach the understanding of the experiences and the articulation of similarities and differences in the meanings and human experiences of people with kidney transplantation and candidates for kidney transplantation. Although it is not possible to make generalizations of the results of this study, particular data are reached with transferability to other populations with similar characteristics [6,7,14]. This article followed the COREQ [Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research] criteria to enhance its quality and clarity [21].

Study and Sampling Population

An intentional sampling was carried out, obtaining a final sample consisted of 11 people with a history of ERD: 7 candidates to receive kidney transplant and 4 transplanted, who received health services in the High Specialty Medical Unit of Mérida [UMAE] of the Mexican Institute of Social Security [IMSS]during the period from November 2019 to February 2020.

Data Collection

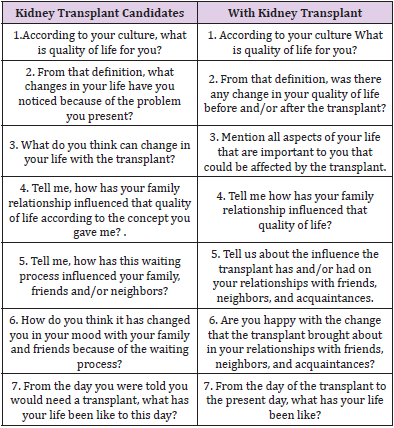

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted during their follow-up consultations. Interviews lasted 30 to 40 minutes, were recorded in audio format, and field notes were taken. Table 1 presents the questions asked during the semistructured interviews.

Ethical Considerations

The study respects ethical principles: beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice and autonomy. The research study protocol, with folio R-2018-785-129, was approved by the ethics committee of the High Specialty Medical Unit of the Mexican Social Security Institute. The testimonies presented herein are referenced with codes to safeguard the identity of the participants.

Information Processing

Semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim and then analyzed using content analysis. This analysis process consisted of:

1. Encoding the data and establishing a data index.

2. Categorize the content of the data into meaningful categories; and

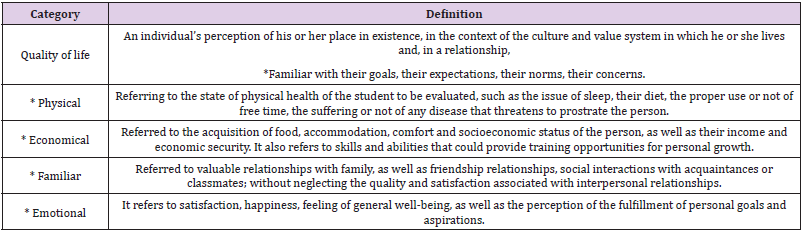

3. Determine the topics related, in this case human responses, to the previously defined categories [7,22]. In the results section, tables are presented that allow to visualize the categories of analysis delimited in Table 2 from Urzúa and Caqueo [23], the human responses within the categories and, finally, testimonies of the participants; all of the above accompanied by interpretive narrative.

Quality Criteria

Once the transcript of the interviews was completed, the 11 participants were asked to verify that the information interpreted was correct. Also the protocolization related to the organization of the data, the detailed and meticulous description of the selection of the sample and the context in which the study is carried out, facilitate the possibility of transfer and reproducibility of the same in similar conditions, thus providing another criterion of qualitative quality.

Characteristics of the participants Years of age were a median of 37 [mean 39]and SD=13 in the 11 participants. In people who were candidates for RT, the median was 37 [mean 41]and in those with RT it was 35.7 years [mean 41), respectively. In the latter group two people were 6 months or less old after receiving RT, one was 1 year old, and one person was 10 years old. Table 3 shows that the majority of the total sample was made up of men who worked as employees.

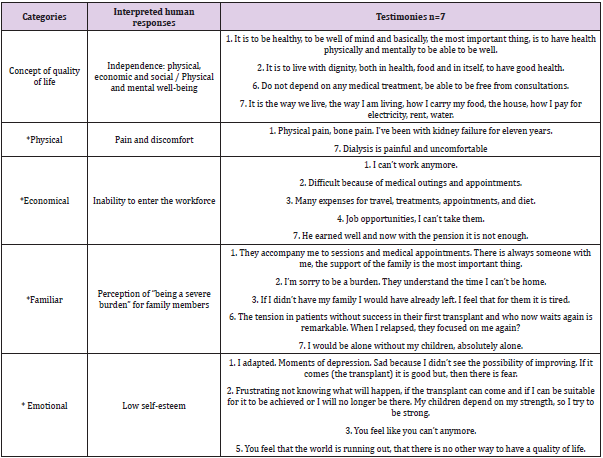

Quality of Life: Perception in Kidney Transplant Candidates

Table 4 shows the interpretations related to the categories: concept of quality of life with their respective domains: physical, economic, family, and social, then the identified human responses are presented. Most of the participants said that quality of life is to be well physically, mentally, and emotionally, as well as to have all the basic services and not depend on renal replacement treatments: dialysis or hemodialysis. In the physical domain, people highlight discomfort, pain and discomfort related to the procedures of renal replacement therapies or the body itself: chronic or bone pain, for example, these human responses largely condition the inability to enter the labor field. In the economic domain, the participants report that they are unable to carry out the activities of any employment due to physical disability, and therefore, consider that their monetary income from a trade or employment is limited, scarce or null. In addition, they stressed that the economic resources are focused on financing the management of the health itself: laboratory tests, transportation, extraordinary treatments, appointments, and medical consultations, among others; these efforts are complicated precisely by the lack of monetary inputs.

In the family domain, people identify the importance of the support, care, and understanding they receive, received, and expect to receive from their family in the ups and downs related to their state of health and well-being. In this regard, some express feelings of feeling a burden for their relatives for the extra activities that the latter perform in health management, which generates tension and uncertainty. However, the interviewees expressed the motivation generated by their family environment: mothers, children and grandchildren, among other ties, drive the desire to want to get out of their problem and be patients waiting for the transplant. In the emotional domain, each of the people interviewed expressed their affectation at different points that leads them to present low self-esteem: fear, frustration, depression, sadness and uncertainty are some of the emotions they expressed among their testimonies. Participants follow a continuous coping process, because not every day they feel with all the energy and motivation to continue with everyday life. The emotional perception of the interviewees was reflected in their features during the interviews, they touched points that led them to cry, they expressed how difficult it is to live with a dysfunctional organ, the uncertainty before the latent complications that can even make them lose their lives.

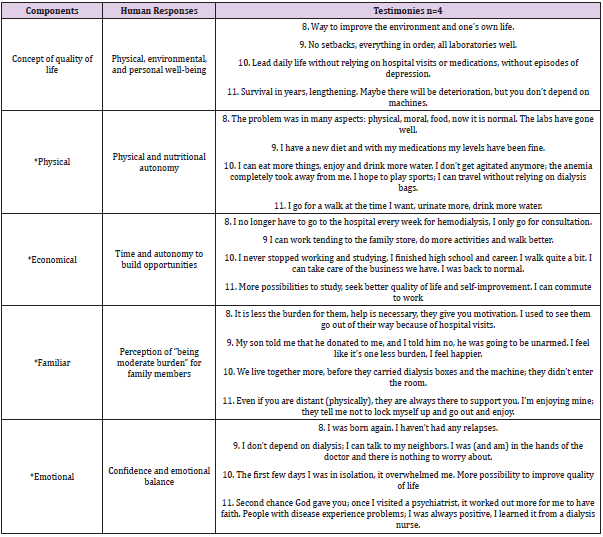

Quality of life: Perception in People with Kidney Transplantation

Table 5 shows that most participants consider that quality of life involves physical, environmental and personal well-being as components. For one of the interviewees, it means no longer relying on external factors to sustain life; another considered that the longer he can extend his life is better for the quality of it, considered that discomforts are companions of life. In the physical domain, the interviewees expressed the freedom to perform various activities and eat food without affecting their quality of life. They expressed that they could move and travel without thinking about the need to carry too many supplies related to their treatment. They also stated that they can eat food without causing discomfort or altering their clinical parameters, especially water, which was previously restricted. In the economic domain, participants report that they have time and autonomy to build opportunities for insertion into trades, jobs and vocational or educational training. One case mentioned that the ability to acquire economic resources improves their quality of life, another participant reports that they can work freely without thinking about the times of some renal therapy, finally, a case refers that they returned to normal by fully taking these opportunities that they previously addressed discreetly.

In the family domain, the perception and feelings of being considered a burden on their families has decreased along with the amount of care related to renal replacement therapies from which transplanted participants are already exempt; people mentioned that despite the constant support of their relatives there was a physical distancing seeking to reduce the crossing of infections, a situation that in recent times has ended and they can share more time and experiences together. In the emotional domain, trust and emotional balance were interpreted in the participants. Two people mentioned that they feel they have a new opportunity before life, to restart it and have new experiences that they previously did not consider possible. Two people referred to the need to have confidence and know how to take the advice of health personnel: doctors and nurses. Finally, one participant described that he was overwhelmed by living a few days in isolation after his transplant, necessary to prevent infections, but at the same time accepts that it is necessary to improve his quality of life.

The quality of life of people with a history of renal pathologies is affected since the first clinical manifestations, the QoL in this sector has shown deficiencies, low levels or areas of opportunity with respect to the rest of the population [24]. Physical, environmental and personal well-being are part of the conception of quality of life in people with renal pathologies, whether they have been transplanted or not. In the early stages of the disease there are a series of negative perceptions of the disease and its mediate and immediate quality of life that, ultimately, can influence their coping actions, these perceptions can trigger anxiety, depression, coping, autonomy, self-esteem and accelerated progression of the disease [25]. In the identification of human responses in patients with chronic kidney disease, the main physiological risks related to this pathology have been highlighted. Farias et. al. points out the overstating of biological and complication-related human responses by nursing staff providing care to patients with nephropathies in a renal center. Among 24 diagnostic labels identified, the most frequent were “risk of infection”, “excess fluid volume”, “hypothermia”, among others whose main domains were located in Safety / Protection and Activity / Rest, on the other hand, “low situational self-esteem” was ranked 16th in frequency [26] corresponding to the Self-perception domain in the NANDA-I [20]. The above shows what Spilogon et. al. points out as an area of opportunity in the nursing process because it has the flexibility and openness to consider the perceptions and preferences of the user, in this case of the patient with nephropathies [27].

In the emotional category, low self-esteem was detected in participants with CKD without transplantation, and that is that a patient with CKD has needs for recognition and esteem, so the people in charge of their care should promote favorable behaviors in coping with the pathology and attachment to treatment, avoiding judging and repressing the failures of our human condition [28]. In contrast, participants who had received a kidney transplant manifested confidence and emotional balance, something that could be considered normal after receiving the expected transplant according to Tucker, et. al. [29]. From a quantitative approach Rocha et. Al. point out that the higher the quality of life, the better the assessment of the self-esteem of people with chronic kidney disease after transplantation [30].

In the economic category, while people who had not received kidney transplantation conceived the inability to enter the workforce among their perception of quality of life, those who had received kidney transplantation indicated greater time and autonomy to build job and academic opportunities. Reports indicate that patients with chronic kidney disease face many barriers to staying or joining the workforce after starting dialysis: limited opportunities, lack of financial resources to invest, fatigue and other symptoms of kidney failure, potential loss of disability benefits or medical follow-up, dialysis scheduling, and employer bias. The societal perception that patients with CKD cannot work completes a vicious cycle of low employment expectations [25,31]. In the family category, the perception of “being a burden” for family members influences is an important component in the perception of the quality of life of people with transplantation and without kidney transplantation. Evidence indicates that family members of patients with a history of renal pathologies manifest sleep interruptions, depression, anxiety, among other disorders associated with unforeseen responsibilities related to the treatment and logistics of their relatives; they must also deal with insufficient information, medication regimen and be accompanied by periodic hospitalizations [32]. NANDA International classifies problems into plausible diagnostic labels of interventions focused on promoting the health of individuals, the family. and community, we can mention: Risk of fatigue of the role of caregiver, Fatigue of the role of the caregiver, Dysfunctional family processes, Willingness to improve family processes, among others [20].

In the physical category, participants without kidney transplantation are identified as a condition for quality of life, a common and often severe manifestation in various populations with CKD; with prevalence’s of 40% to 60% is a strong imperative to establish the management of chronic pain as a clinical and research priority [33]. In this regard, the labels acute and chronic pain are available in NANDA-I [20]. Although pain and physical limitation decreases after a kidney transplant, it is important to mention that the physical and nutritional autonomy indicated by the participants of the present can generate an excess of confidence and the acquisition of unhealthy practices. Physical training regulated by physiotherapy specialists appears to be safe in kidney transplant recipients and is associated with improved quality of life and exercise capacity [34]. With respect to diet, the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets have been shown to be the most beneficial dietary patterns for the population after kidney transplantation by focusing on less meat and processed foods, while increasing intake of fresh foods and plant-based options. [35]. Knowledge and awareness in the renal transplant population should be a cornerstone of therapy and an integral part of nursing responsibilities. Therefore, nurses should educate patients about self-care behaviors and remind them of the dangerous complications of abandoning them [28].

In participants who had not received a kidney transplant, there was an expectation of receiving a kidney transplant to improve their quality of life and from it to improve their quality of life. In this aspect we can mention the benefits before the expectation of receiving a kidney transplant mentioned by Santos et. al. who in a group of people with Brazilian nephropathies detected that patient who were not waiting for transplantation were at risk of poor quality of life, mainly in the emotional and physical aspects; those who were not awaiting transplantation died more frequently in the next 12 months [36]. However, betting on kidney transplantation to improve the quality of life in patients with nephropathies is not entirely recommended, in this regard we can cite the studies of Schulz et. al. and Smith et. al. published in 2014 and 2019, [29,37] who reported that before transplantation patients can overestimate gains in quality of life without finding significant improvements in quality of life after being transplanted.

Kidney transplantation is not a guarantee of improvement in quality of life in all patients with nephropathies, in the present study, those people who had received the kidney transplant did not consider an absolute improvement in their quality of life. The literature notes that kidney transplants can provide dramatic improvements in quality of life and health status, however, the effects on improvement are not universal and patients live in constant uncertainty as they are aware of the likelihood of graft dysfunction [29]. There are samples that have indicated that the expectation about the functionality or rejection of the graft generates greater fear and uncertainty than death itself [38]. The results on the perception of quality of life in people receiving renal replacement therapy support the trend of the last decade focused on the analysis of this category beyond only assessing life expectancy [39]. The limitations of the present are the risk of bias due to the same interpretative approach and the inability to generalize the results to the study population. To compensate for the above, criteria of methodological rigor were followed and from a particular context the search for generalities was made, reinforcing the results with respect to other studies [21].

In transplant patients, a perception of absolute or discomfortfree quality of life is not achieved and human responses that require care and interventions to achieve the highest level of well-being are still manifested. The construction of the concept of quality of life includes physical, mental, personal and social elements feasible to document and in which to exercise interventions for the benefit of the people treated and their families, it is evident that human responses do not only obey physiological needs.