From Scientism to Qualitative Inquiry – The Transformative Impact of a Reflexive Exercise

Introduction

In this auto ethnographic piece, I tell the story of how I “rediscovered” myself at the course of my doctoral programme in Health and Wellbeing. I reveal how I moved from being an “incurable” positivist to a qualitative inquiry enthusiast. I highlighted the role of reflexivity in this transformation. I discussed the initial troubles I had with letting off my established identity in the positivist paradigm and embracing the qualitative inquiry approach. I also mentioned the role of Dean Holyoake (DH) and Hilary Panigua (HP), my doctoral modules co-ordinators, in my transformation in research positionality. I also briefly appraised the competition between the notion of objectivism and subjectivism. I chose subjectivism over objectivism in the exploration of social phenomenon because I feel it affords me the space to use my voice in the research process. This is the freedom I never had in the previous years that I was buried in the positivist paradigm. Story provides the medium through which people understand and interprete their existence (Clandinin et al, 2017).

Human meaning making unfolds through the negotiation of multiple real and imagined scenarios and storylines and visible representations play a great role (Märtsin [1]). Meanings are also seen as open-ended and unfinished as utterances are seen as both responses to previous utterances, as well as initiations of new utterances in the endless cycle of unfolding semiosis (Salvatore, et al. [2]). Inner voice is found when we look deeper within ourselves, thoughts, experiences and our unsettled struggles in doing so (Dashper [3]; Laurendeau). This paper tells the story of how I found my inner voice. It highlights the change in my research positionality. It is through story saying that people work out their changing identities (Frank [4]).

I would be telling my story in a messy style. Messy style of writing texts is an art-based method that frees the writer from the restrictions of traditional ways of research writing (Miller, 2008). I agree with Miller that “it’s ruse to give appearance of certainty and to bring order to chaos” (P 93). My priority may not be to seek order in either in my structure of writing or content in this paper. My interest would be to tell the story of how I re-discovered my non-linear self. A luminal space has been created in qualitative research where “messy, uncertain, multivoiced texts, cultural criticism, and new experimental works will become more common, as will more reflexive forms of fieldwork, analysis, and intertextual representation” (Denzin, et al. [5]).

My background was laboratory science! I was driven by the notion of positivism (Bianchini, et al. [6,7]). For me, there was always a reality out there waiting to be known (Aslan, et al. [8,9]). I harshly silenced my inner voice and literary imagination. Anything that was not clearly “logical”, was viewed by me as “unscientific” (Adaka, et al. [10,11]). I had spent decades in linear reasoning and viewed things only in terms of cause and effect. I remember I was a “science” student in my secondary school and dealt with quantitative data at that level. In my both my bachelor and master’s degrees, I used quantitative approach to collect and analyse data. I was a purist and was driven by the notion of objectivity. Then I enrolled on a professional doctorate programme in Health and Wellbeing in the University of Wolverhampton, UK in September 2017. This is a part- time programme with four taught modules and a dissertation module.

The four taught modules were “Positionality and the Researcher”; “Advancing Professional Practice”; “Undertaking a Critical Literature Review” and “Understanding Research Structures and Processes”. There I met Doctor Dean Holyoake (DH) and Doctor Hilary Panigua (HP) who were the modules coordinators. DH taught the first two modules (Positionality and the Researcher and Advancing Professional Practice) while HP taught the last two modules (Undertaking a Critical Literature Review and Understanding Research Structures and Processes). They both have background in the use of qualitative inquiry as a research approach. They advocated for qualitative inquiry and tried to introduce my doctoral cohort to it. But I was not comfortable with that as I had engaged in quantitative approach all my life until this doctoral programme. I thus found myself initially in a difficult and awkward situation.

I was neither experienced in qualitative inquiry nor looking forward to it on the doctoral programme. It was disappointing for me to find out that the programme required me to explore qualitative inquiry. However, as I continued on the programme, I began to undergo a progressive transformation in my research positionality. Before coming for the doctoral programme, the notion of scientism gave me no space to explore social phenomena interpretively (Baron, et al. [12,13]).

My Experience of the Reflexive Activity in the Doctoral Classroom

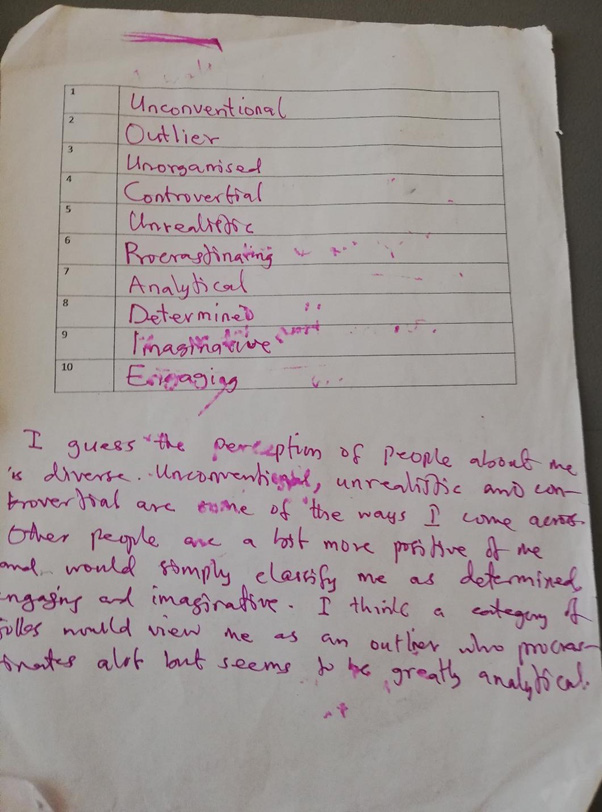

In 2018 and after the first doctoral module (Positionality and the Researcher), my doctoral cohort progressed to the second module (Advancing Professional Practice). In this module we were meant to learn among other things, the role of reflexivity in our professional practice. DH had observed from the first module that my entire cohort was more inclined to the positivist paradigm. He was concerned that our voice was lacking both in our professional practice and in the research process. He felt it was important for us to find our voice. He argued that this would help to improve professional practice. But it seemed difficult for DH to get me and my doctoral mates into qualitative inquiry by merely debating it. He had to find a way of breaking the barrier between we the doctoral students and the qualitative inquiry. Finally, he came up with a class exercise for every one of us. He passed a sheet of paper to each of us (see Figure 1 below) and asked us to write up to ten words on the how others viewed us.

When then to turn these words into sentences within just a paragraph. We were about twelve in all. Everyone engaged in this task. I also dutifully engaged in it unaware of what would come out of it. It seems very easy for scholars to treat their professional identity as sacrosanct and fight to advance it. This puts them in the bony place of antagonism to alternative views and debates (Plump and Geist-Martin, 2013). Professional practice creates ideological space for a firm construction of professional identity using the bricks of cognitive powers and a massive sense of self triggered by shared stories and professional recollections (Wenger, 2008). This tends to “territories” professional knowledge and identity (Sanders et al, 2011: 117).

The problem with this is that it places ideological conservatism over negotiated meanings when we drift into a new terrain requiring the exploration of multiple possibilities in our ontological voyage. Sticking inflexibly to one’s gun is likely to generate tension among one’s compatriots in the journey be they peers or supervisors. But letting go would produce the uncomfortable feeling of being exposed and vulnerable in the journey and being ostracised from those in our initial circle (Petty et al, 2012). The question becomes how will the ‘researching professional’, the ‘practitioner-researcher’, the ‘scholarly practitioner’ (the nomenclature may be unlimited) be received? Although the cultural environment opens up liminal spaces for the construction or deconstruction of our identities, our perception of threats to our established identities is a key driver of whether we will let go of the old and surf through for a new identity or not (Plump and Geist-Martin, 2013).

Figure 1: A reflexive exercise on selfhood in my doctoral class session. We were required to write up to ten words of how we thought people viewed us. We were then to put these words into a paragraph.

I discovered that as I let go of my bias against qualitative methods and their assumed negative consequences on my doctoral and professional future, I began to see things differently. I suddenly started realising that outside of my “scientific self” who wanted to follow laid down procedures, I also had a fragmented self, which I had not explored until then. In my usual interactions with friends and other people, my behaviour was not based solely on the “scientific approach”. As I utilised the space provided by the doctoral class exercise to think deeply on what people thought about me, a new me began to emerge right in front of me. It seemed like the scales began to fall from my eyes at that moment. Multiplicity of selves within a person has been established (Gergen [14]; Markus and Wurf, 1987). I feel that the notion of holism is thus a myth as individuals tend to be fragmented at various degrees (First, et al. [15-18]).

It began to occur to me that I had silenced my “fragmented self “in deference to my “scientific self”. I then appreciated in a new way that certain attributes were always present in me which made me peculiar and set me apart from others. I had blind spots on who I was because of the delusion to satisfy the notion of scientism. I was ignorant of the possibility of the use of art-based methods for health research (Boydell, et al. [19-21]) engaged first year medical students in a reflective exercise that is qualitative in nature. Most of the tutors involved reported the exercise as being beneficial to them, to student learning, and to curriculum development. In another study on the impact of reflective practice on emerging clinicians’ self-Care, (Curry [22]) found that participants reported being better able to care for themselves both personally and professionally. They had improved emotional health, better outcomes regarding their job (satisfaction, sustainability, and longevity on the job) and developed a new standard (model) for their future practice. The reflective exercise I partook in gave me a shift in perspective and mode of engagement in research and professional practice with the benefits highlighted above. I became open to qualitative inquiry method. Qualitative studies help to access rich data that is normally unavailable or unacceptable for quantitative research (Bast, et al. [23,24]). I believe there is so much to explore and know in Health and Wellbeing than the restriction of scientism allows (Alexander, et al. [25,26]).

After the various sessions with DH on my doctoral programme, came the Hilary Paniagua (HP) experience. She took us on the remaining two taught modules as earlier mentioned. She wanted us to think in a “non-linear” way as well. Although I found the entire processes initially stressful, I was undergoing a transformation in methods of research inquiry. Conducting qualitative research changes the researcher in many ways. It exposes their biases, beliefs, political learning, and epistemological positioning on one hand and reconstruct them on the other hand (Palaganas, et al. [27]). The reflexive classroom exercise and several discussion sessions with DH and HP in our doctoral class sessions made me to begin to think laterally and to romanticise the notion of subjectivity. This was something that I was indisposed to for years before the reflexive class exercise. The exercise opened me up to see that there are multiple realities when it comes to the exploration and consideration of social phenomena.

As I reflexed on the words above, I tried to make sense of by constructing a paragraph from them as shown above. The paragraph unearthed some salient characteristics, which I had not given much attention. I found from the words and the paragraph that I was not simplistic and would not fit into a mere “cause and effect” mode of looking at phenomenon. I found the words and the paragraph therapeutic. I was comfortable with the picture they painted about how people saw me. It made me to feel that my authentic self was not apparent to me all this while. I suddenly realised that if I came out of the confines of positivism, I would achieve more in research and professional practice. It would free me from merely playing to the rule books of scientism. I would be able to soar without restrictions in the realm of interpretivism. Reflexivity is a “deconstructive exercise for locating the intersections of author, other, text, and world, and for penetrating the representational exercise itself” (Macbeth [28]). It is etymologically rooted in selfreflection and critical self-reflection. The contemporary move to analytic reflexivity is achieved through the act of “turning back upon itself” (Macbeth [28]). This is about the turning back of a text, an inquiry or a theory onto its own formative possibilities (Clifford, et al. [29-31]). Contemporary expressions of reflexivity have been linked strongly to critical theory, standpoint theory, textual deconstruction, and sociologies and anthropologies of knowledge, power and agency (Anderson, et al. [32-36]). It thus culturally, radically and relatively situated (Macbeth, et al. [28,37]).

Three broad forms of knowledge have been identified - the technical, practical & emancipatory knowledge (Taylor [38]). The first two forms (technical and practical) use the tool of reflection while the third form (emancipatory) which is as a result of the first two forms, uses reflexivity (Lipp [39]). Reflexivity gave me the power to break the chains of positivism and freely flow in the interpretivist paradigm. It helped me to build self-awareness which is an invaluable tool in stimulating professional development (Bolton, et al. [40-42]). It helps in turning the problem of subjectivity into a great opportunity to explore its challenges (Carolan, et al. [43,44]). Self-awareness, which is consequent upon reflexivity, is important in order for a researcher to have a voice in their research (De Vault, et al. [45-48]). I had spent all my life until now learning other people’s views and submissions. All through my academic training and work experience, I had dealt with professionals and researchers who prided in and emphasized objectivism as a way of knowing reality. In fact, linear parameters were utilised in examining and evaluating my various performance [49]. I had taken on board all these learnings and the readings from “scientific texts” until I had cancelled out alternative ways of looking at things [50]. Scientism birthed a delusion in me on what could be acceptable as data and how a phenomenon should be interpreted (Crawford [26]). The notion of scientism restricts and excludes a researcher from exploring realities, which cannot be measured (Alexander, et al. [25]). This is an albatross around the neck of creative studies that could have revolutionise health and wellbeing practice (Baron [12,23]; Boyll et al, 1996).

Conclusion

My reflexive exercise in the doctoral class had a transformative impact on me [51-55]. It helped me to discover my true selfhood and to explore the qualitative inquiry approach. This is something that was not possible previously due the hold of the notion of scientism on me. I felt emancipated from the confines of positivism and found my voice [56]. Health and Wellbeing researchers and professionals need to engage in reflexive exercises from time to time. Although it might initially seem illogical and unscientific, it would help in creating self-awareness and open the portal for new possibilities [57-59]. This would enrich research and professional practice. The use of art-based methods such as poetic inquiry helps to elevate discourse from the plane of mundanity to the level of metaphoric representations [60]. Their inclusion in health and wellbeing research will help to close the false gap between research in arts and sciences in the academia [61]. My experience has shown that they are useful in research experimentation and innovation [62].

My Reflection on the Doctoral Classroom Task I Provided – Dean Holyoake

When I handed out the reflexive exercise in the doctoral class session, I was hoping that it would provoke my students to some lateral reasoning [63-65]. They were all very strong in positivist views and protective of their views. My aim was to invite them from their shell to the unfamiliar and murky terrain of subjective meaning making [66]. I figured out that starting from exploring their selfhood reflexively was critically important to achieving this [67]. Looking back, I can see the value of that exercise [68]. Although a new way of knowing might come across as disarming, letting go of the previous knowledge is necessarily in order to negotiate new meanings [69].

My Reflection on Doctoral Support Processes – Hilary Paniagua

Mentoring doctoral students and providing feedback can be a herculean task [70]. Sometimes, one cannot escape providing a seeming judgement on their work [71]. I feel that this helps the students to reflect more on their positionality and the concepts they are discussing [72]. The transformation I have seen in Enemona Jacob strengthens me to continue on the journey of mentoring doctoral students [73-76]. Questioning what we know to see if there are new ways of knowing helps us to explore things, we were blind to [77]. I feel that the classroom is a big field for experimentation. Things could go either way [78]. Therefore, although I wanted an opportunity for a lateral reasoning by my doctoral students, it would not be everyone that might have embraced it [79]. I however feel that providing an opportunity for people to engage with a new way of thinking has the potential to birth new possibilities [80- 82]. Such exercises have the potential to enrich staff and students’ experience on one hand and to add to curriculum development on the other hand [83-114].

For more Articles on: https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.