The article begins with the following Advance Organizer Quiz to Retrieve, Use, and Organize the Materials presented in this paper. Advance organizer – please answer true or false to the following questions:

a. Identifying the site of origin and location about the hip joint is a useful method to classify hip pain. TRUE

b. The deep gluteal space borders posteriorly by the gluteus maximus, anteriorly by the posterior acetabular column, hip joint capsule and proximal femur, laterally by the lateral lip of the lina aspera and the gluteal tuberosity and superiorly the inferior margin of the sciatic notch. TRUE

c. Deep gluteal syndrome (DGS) involves compression of the sciatic or pudendal nerve by any anatomical structure within the deep gluteal space. TRUE

d. Piriformis syndrome is a prevalent subtype of DGS. TRUE

e. Patients who participate in competitive sports have an increased risk of developing proximal hamstring syndrome. TRUE

f. Definitive imaging findings have yet to be established in piriformis syndrome. TRUE

g. Use of advanced magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) techniques and endoscopic correlation has increased awareness of the anatomy and pathologic conditions of the deep gluteal space. TRUE

h. Diagnosis of DGS may include specified history and physical examination findings, plain radiographs (to rule out hip and spine pathology, and calcifications), magnetic resonance neurography (to evaluate peripheral nerves and sciatic nerve aberrancy) and endoscopic decompression. TRUE

i. Endoscopic decompression of sciatic nerve entrapment may be an effective and minimally invasive approach for deep gluteal syndrome. TRUE

Hip Pain

Hip pain often presents as a challenging symptom affecting individuals of all ages and may be associated with numerous underlying causes or etiologies. The hip forms the joint between the upper end of the femur (thighbone) and its socket in the pelvis located in the region of the groin. A stable, major weightbearing ball and socket synovial (fluid) joint, the hip joint allows for significant mobility, formed by a connection between the pelvic acetabulum (the cup-shaped socket in the hip bone) and the head of the femur (the thigh bone) [1]. Forming an articulation from the lower limb to the pelvic girdle (distinctively dissimilar in men and women as to function and size), the hip joint is, thus, intended for stability and weightbearing. Comprised of bone, cartilage, ligaments, muscle, and a lubricating fluid, painful symptoms of a hip disorder will differ depending on the cause of the underlying disorder and the part of the hip joint causing problems [2]. Once hip pain becomes progressive, burdensome and unyielding, patients have no option other than to seek assistance from their medical providers.

As noted in the article Hip Pain: Relation to Anatomical Location and Underlying Pathology [3], a consensus among experts on how to classify hip pain remains undetermined. One method to classify hip pain, however, recognizes the origin of the pain as,

(a) Anterior,

(b) Posterior and

(c) Lateral.

The location of hip pain is further identified as,

a. Within a joint (i.e., intra-articular),

b. Around a joint (i.e., periarticular) or

c. Outside a joint (i.e., extra-articular) [4].

Utilizing essential aids of careful history-taking, relevant physical examination (PE) techniques, and appropriate laboratory testing and imaging studies is fundamental to evaluate underlying causes of hip pain based on origin and location. This review will focus on posterior hip and buttock pain in the adult highlighting DGS as a recently classified and somewhat unfamiliar entity with various subtypes (i.e., piriformis syndrome, gemelli-obturator internus syndrome, proximal hamstring syndrome).

Posterior Hip and Buttock Pain

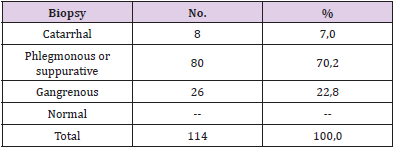

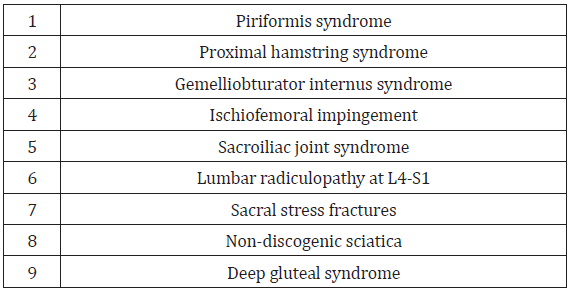

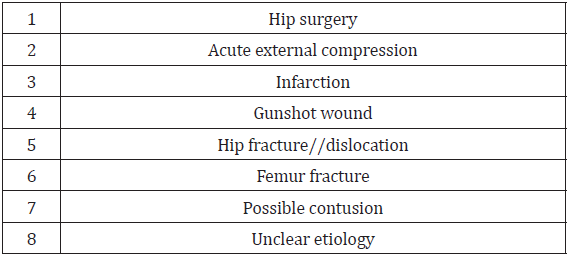

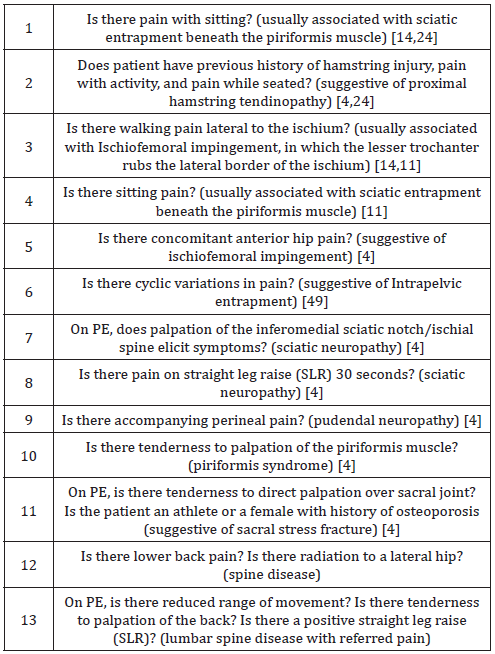

Although awareness about posterior hip and buttock pain is less recognized than anterior and lateral hip pain [5], improved understanding and knowledge of the anatomy and neural kinematics (forces which cause motion) of hip movement has helped posterior hip and buttock pain become more recognized and understood [6-8]. As a result, the ability to rule out lumbar spine pathology with corresponding lack of imaging findings, allows for other considerations of posterior hip pain or nondiscogenic sciatica (sciatica-like pain) [9]. Other considerations may include any lesion involving the sciatic nerve (originating from L4 to S3), thus making posterior hip and buttock pain often difficult to distinguish from sciatica [5]. Table 1 identifies common causes of posterior hip and buttock pain. DGS, as a separate entity, is a group of various subtypes, previously described as piriformis syndrome (PS).

Historical Perspective of DGS

To understand DGS, an overview of PS is important as all PS are DGS but not all DGS are PS [10]. Traditionally known as “piriformis syndrome” DGS is now the favored term to describe the presence of pain in the buttock through identification of several locations where there may be entrapment of the sciatic or pudendal nerve [5]. Often undiagnosed or mistaken for other conditions, the concept of DGS now encompasses beyond current understanding of posterior hip pain due to nerve entrapment past the traditional model of piriformis syndrome [5]. Historically, in 1928, the association between sciatic nerve pain and the piriformis muscle was first described [11]. In 1936, American surgeon Thiele described the origins of PS with the piriformis muscle (originating on the front of the sacral bone and inserting on the Major Trochanter of the Femur) compressing the sciatic nerve as it leaves the buttock just below the greater sciatic foramen [10]. In 1999, McCrory and Bell [12], described the PS as only one component of the deep gluteal syndrome (DGS), and further described a broad spectrum of pelvic conditions not associated with piriformis caused similar symptoms [5].

Anatomical variations of the sciatic nerve, however, may contribute to other conditions other than PS, such as coccygodynia and muscle atrophies, if it divides into other nerve components within the pelvis [10]. As a result, the prevalence and the clinical signs related to chronic muscle contractions in the deep gluteal area appear to be more abundant than previously described [10]. In addition to the Piriformis muscle, other deep pelvic muscles like M. Obturator Internus, M. Levator Ani, M. Gemelli and M. Coccygeus may be involved in the pathology and may lie within the space [13]. Thus, the term “deep gluteal syndrome” has evolved to denote many different pathological and etiological conditions, with similar treatment, but with a more well-defined and precise diagnostic term now labelled DGS [10]. Because of ongoing innovations in the understanding of anatomy and neural kinematics of hip movement, identification of DGS is now possible. Traditionally, prolonged and/ or excessive contraction of the piriformis muscles were clinical symptoms associated with PS [11].

Advances in hip and joint kinematics, however, involving the mechanics of pure joint motion without reference to the masses or forces involved, now provide better awareness of hip function and anatomy [14]. In addition, hip kinematics identify a number of areas within the deep gluteal space where the sciatic nerve may be susceptible to entrapment [11]. Any contents of deep gluteal space, including the space that contains piriformis, obturator internus/ externus, gemelli, quadratus femoris, hamstring, gluteal nerves and lateral ascending vessels of the medial femoral circumflex artery, can cause sciatic nerve entrapment syndrome [8]. Furthermore, hip kinematics identifies the occurrence of posttraumatic DGS with development of scar tissue around the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve or with adherence of the nerve to the posterior pelvic column [15]. Distinct clinical symptoms and specific physical examination techniques, including provocation tests, are essential to diagnose sciatic (and pudendal) nerve entrapment [8,16]. Use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis and electrodiagnostics studies is significant in diagnosing DGS and identifying pathological conditions entrapping the nerves [14]. As such, early detection and treatment of DGS as an entity should now be the standard of care. Nonsurgical and surgical treatment options as presented below may assist in the management of patients with posterior hip and buttock pain related to DGS.

Common Causes of Posterior Hip and Buttock Pain

Pain at the posterior hip and buttock is an often underrecognized manifestation of femoroacetabular joint disease and most commonly includes radicular origins referred from the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint [4]. Other sources include pathology within the hip joint itself (labral tears, synovitis or chondral injuries) that can refer pain to the buttock or lower back [17,18]. Similarly, proximal hamstring pathology, piriformis syndrome, tendinopathy of the obturator internus/gemelli complex, ischiofemoral impingement and sacral stress fractures are important considerations as causes of posterior hip and buttock pain [4]. As previously noted, early descriptions of PS postulate that prolonged or excessive contraction of the piriformis muscle over time might precipitate deep gluteal pain [11]. If anatomic piriformis abnormalities involve the sciatic nerve, clinical symptoms may include extreme gluteal and lower back pain [11]. Hip joint pathology may refer pain to the knee, while pain referred to the leg or foot generally indicates lumbar spine radiculopathy.

Sciatic and pudendal neuropathies can refer pain to the posterior hip [14]. Posterior hip or nondiscogenic sciatica (sciaticalike pain) can be caused by any lesion originating from L4 to S3 involving the sciatic nerve can cause posterior hip or nondiscogenic sciatica (sciatic-like pain [19]. Genitourinary causes (e.g., intrapelvic impingement) [20,21], gastrointestinal and vascular pathology [4] while beyond the scope of this review should be considered as other potential sources pf posterior hip and buttock pain. (See Table 1 for differential diagnosis of posterior hip and buttock pain.)

DGS as a Cause of Posterior Hip and Buttock Pain

As a relatively unknown but increasingly recognized disorder, DSG describes the presence of pain in the posterior hip and buttock caused by compression or entrapment of the sciatic or pruendal nerve by any anatomical structure or nondiscogenic pelvis lesions in the deep gluteal space [5,13,22] The structures that can be involved in sciatic or pudendal nerve entrapment within the gluteal space include the piriformis muscle [23,24], fibrous bands containing blood vessels, gluteal muscles [24,25], hamstring muscles [24,25], the gemelli-obturator internus complex [24,25], vascular abnormalities [21] and space occupying lesions [24,25]. The DGS includes piriformis syndrome, gemelli-obturator internus syndrome, the ischiofemoral impingement syndrome and the proximal hamstring syndrome [13,14]. As described by Martin, et al. [14,8], the borders of the deep gluteal space are defined by the following;

i. Posteriorly, the gluteus maximus,

ii. Anteriorly, posterior acetabular column, hip joint capsule and proximal femur,

iii. Laterally, lateral lip of linea aspera and gluteal tuberosity,

iv. Medially, sacrotuberous ligament and falciform fascia,

v. Superiorly, inferior margin of the sciatic notch,

vi. Inferiorly, proximal origin of the hamstrings at ischial tuberosity [11,8].

The anatomy of the deep gluteal space is unique in that the nerve enters the pelvis through the sciatic notch and demonstrates a significant mobility with hip movements [26]. A careful history and physical examination assists to exemplify this unique factor by defining the specific site where the sciatic or pudendal nerve is entrapped [14].

Pathogenesis of Deep Gluteal Syndrome

Normal healthy nerve roots generally emerge from the spinal column from the L2 to S4 levels through the neural foramina and join to form a complex entity known as the lumbosacral plexus [27]. Two main components to the lumbosacral plexus include the lumbar plexus (made up of nerve fibers from the L2 through L5 roots) and the sacral plexus (made up of nerve fibers from the S1 through S4 roots) [28]. Divisions from the lower lumbar plexus and upper sacral plexus give rise to the sciatic nerve [27]. The sciatic nerve is the longest and thickest (almost finger-width) nerve in the body and is comprised of five nerve roots: two from the lower back region called the lumbar spine and three from the final section of the spine called the sacrum [29]. The five nerve roots come together to form a right and left sciatic nerve [29]. On each side of your body, one sciatic nerve runs through your hips, buttocks and down a leg, ending just below the knee. Branching into other nerves, the sciatic nerve passes through the sciatic foramen and descends into the posterior aspect of the leg until it reaches the popliteal fossa, just below the knee, where it divides into the tibial and common peroneal nerves [27,28].

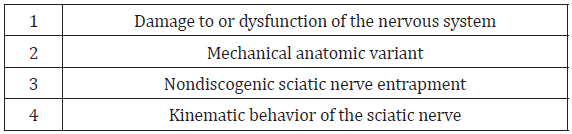

These nerves continue down into the leg, foot and toes. Branches from both the lumbar and sacral plexus also form the inferior and superior gluteal nerves innervating the lateral and posterior hip musculature [27,28]. Branches from the sacral plexus alone converge to form the pudendal nerves, innervating the pelvic floor musculature and perineal sensation [27,28]. Sciatic and pudendal neuropathy associated with DGS may occur following damage to or dysfunction of the nervous system. Compression is commonly proximally where a herniated disc may compress a spinal nerve root [9,30]. The pathogenesis of DGS involves compression affecting the neuronal structures in the lower extremities and involves pain in the buttock caused from entrapment of the sciatic and/or pudendal nerves in the deep gluteal space [31]. Compression of the sciatic nerve in a mild state may present as intermittent due to positioning, with associated reversible ischemia of the nerve [32,33]. Demyelination (i.e., a condition that results in damage to the protective covering (myelin sheath) surrounding nerve fibers) occurs, as compression grows more consistent and chronic [27,34].

Symptoms are usually persistent at this point, and pain and weakness may become more obvious. As compression progresses further, the distal nerve segments will no longer function and Wallerian degeneration may occur [27,28]. In severe cases, the entire distal segment of the nerve can degenerate, similar to the degeneration seen in a nerve transection [27]. Based on current understanding, sciatic pain is usually a result of a mechanical anatomic variant (contrasted to a primary neuropathy) with secondary mechanical compression of the nerve or nerve roots in the deep gluteal region [35]. The narrowing of space between the ischial tuberosity and femur causes hip pain and may contribute to sciatic nerve entrapment. DGS may also include sciatic nerve entrapment resulting from abnormal hamstring pathology [14,11,13]. The hamstring may be strained or sustain an “injury” such as a tendon detachment, avulsion, manifest apophysitis, or tendinopathy [11]. Also known as the hamstring syndrome or the ischial tunnel syndrome, this may also play a role in sciatic nerve entrapment during hip motion [11,36].

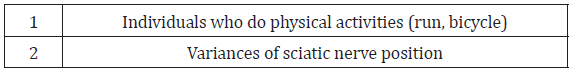

Although there are difference etiologies of nondiscogenic sciatic nerve entrapment, large studies confirm that within the pelvis, the most common site of entrapment is beneath the piriformis (67.8%) [11]. The sciatic foramen is the second most common site of sciatic nerve entrapment (6%) [11]. In the case of the DGS involving the piriformis, if sciatic pain is involved, it is most often because of an abnormality within the piriformis muscle, sometimes associated with a fibrous band that entraps the nerve and decreases sciatic nerve mobility. This can result in painful stretching of the nerve during normal hip and knee movement. Fibrous bands compress the sciatic nerve at the level of the greater sciatic notch extending down to the inferior border of the piriformis. Pathological hypertrophy of the piriformis results in asymmetric enlargement that may also compress the sciatic nerve. The variability in sciatic nerve position as it transverses the piriformis has been considered as a risk factor but to date there is no concrete evidence that variances play a role in sciatic nerve entrapment [11].

The kinematic behavior of the sciatic nerve plays a role in the pathophysiology of DGS as the position of the hip and knee joints affects the tension in the nerve. The sciatic nerve stretches by an excursion of 28.0 mm during a modified straight leg raise with knee extension [8]. This excursion can be limited when the position of the hip joint is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. [31] With hip flexion at 90° and knee extension in full, the sciatic strain increases by a mean of 26%, which may result in neural dysfunction [29]. Thus, impaired gliding of the sciatic nerve can disrupt its normal excursion and induce the deep gluteal syndrome [5]. (See Table 2 for pathogenesis of DGS.)

Prevalence of PS/DGS

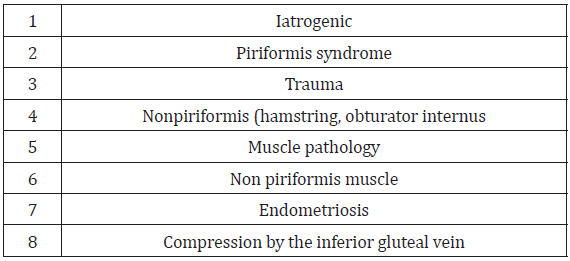

Reported hip pain affects approximately 14% of the population over the age of 60 [37]. Piriformis syndrome may be responsible for 0.3% to 6% of all cases of low back pain and/or sciatica. With an estimated amount of new cases of low back pain and sciatica at 40 million annually, the incidence of PS would be roughly 2.4 million per year [35]. In the majority of cases, PS occurs in middleaged patients with a reported ratio of male to female patients being affected 1:6 [35,38] In a study of 73 patients who fulfilled strict electrophysiological criteria for sciatic neuropathy, hip surgery was the cause in 22 percent, acute external compression in 14 percent, infarction in 10 percent, gunshot wound in 10 percent, hip fracture/dislocation in 10 percent, femur fracture in 4 percent, possible contusion in 4 percent, and unclear etiology in 16 percent [39]. See Table 3 for common causes of sciatic neuropathy. (See Table 3 for causes of sciatic neuropathy.) In a recent systematic review of 481 patients with DGS causing sciatic nerve entrapment undergoing surgical treatment, the most common causes identified were iatrogenic (30%), piriformis syndrome in 124 (26%), trauma (15%), nonpiriformis (hamstring, obturator internus) muscle pathology (14%), sciatic nerve entrapment by non-piriformis muscle in 68 (41%), endometriosis in 27 (6%), and compression by the inferior gluteal vein in eight (2%) [40]. (See Table 4 for common causes of DGS due to sciatic nerve entrapment.)

Clinical Presentation of DGS

Clinical evaluation of patients with DGS may appear vague and ambiguous since symptoms can be inexact and may be mistaken with other lumbar and intra-or extra-articular hip diseases [13]. Characterized by a set of signs and symptoms occurring in isolation or in combination, patients with DGS commonly present with intermittent, paroxysmal, unrelenting and/or persistent pain and/dysesthesias (chronic pain produced by the central nervous system) in the buttock, posterior hip or thigh in contrast to lower back pain [13]. Patients may report sitting pain with inability to tolerate sitting for 20-30 minutes, walking pain, lower back or hip radicular pain, and paresthesia of the affected buttock and inguinal area [13,16,41,42]. In addition, tenderness in the gluteal and retro-trochanteric region and sciatic-like pain, often unilateral but sometimes bilateral, exacerbated with rotation of the hip in flexion and knee extension is another common symptom [13]. Thus, DGS pain can by exacerbated by activity associated with hip flexion, including walking, sitting, reclining, lifting or standing [10].

In addition, antalgic gait or limp, disturbed or loss of sensation in the affected extremity, lumbago and pain at night with improvement during the day are other commonly reported symptoms [5,10,13]. The degree of pain associated with DGS can limit activities and result in sleep deprivation [11]. In contrast, patients with ischiofemoral impingement usually experience a worsening of pain when running or taking larger steps since the distance between the ischium and lesser trochanter becomes narrower during terminal hip extension (long-stride walking test) [43]. Patients with proximal hamstring syndrome, however, may report ischial pain during the initial heel strike (long-stride heel strike test) [5]. Focal neurological signs, including foot drop, are not the typical presentation of DGS [5].

Associated Risk Factors for Posterior Hip and Buttock Pain

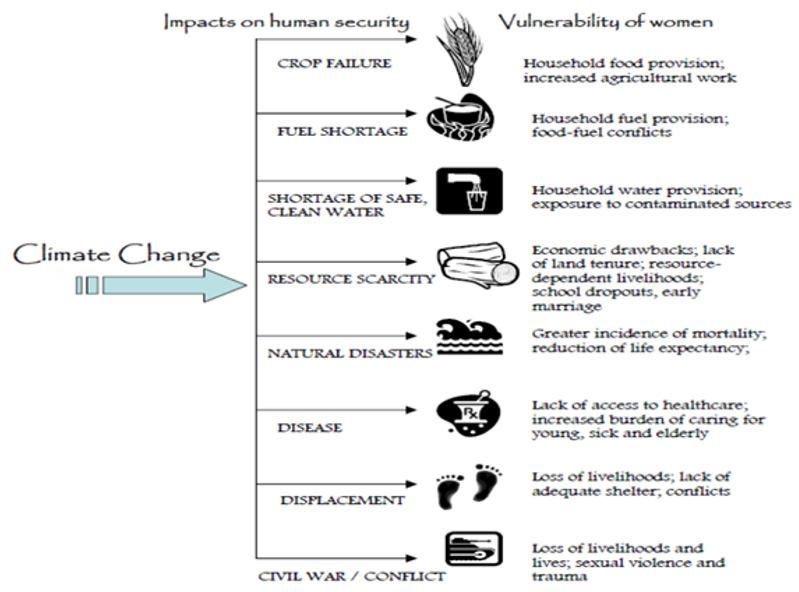

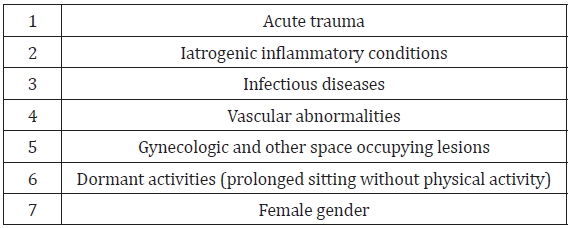

Local risk factors for posterior hip and buttock pain, and in particular DGS, include acute trauma, iatrogenic inflammatory conditions, infectious diseases, vascular abnormalities, and gynecologic and other space occupying lesions [11]. Historically, trauma is the most common etiology related to DGS; this includes hip pathologies presenting with instability including labral tears, hip dysplasia, and ligament teres injury [6]. There is insufficient and unsubstantiated evidence that individuals who run, bicycle, or do similar activities are more susceptible (especially if they do not routinely stretch and strengthen laterally before exercise). Dormant activities, such as prolonged sitting without physical activity may also lead to DGS. In understanding the mechanics of DGS, an awareness of potential exogenous causes of DGS, including hip anatomy, and biomechanics and pelvic kinetics as well as sciatic nerve anatomy are important to consider [11]. Variances of sciatic nerve position may present as a potential risk factor sciatic nerve entrapment, although concrete evidence is lacking. Female gender due to the particular anatomical characteristics of the female pelvis possibly related to hormonal changes, pregnancy, structural abnormalities such as hip dysplasia and femoral anteversion [6]. (See Table 5 for risk factors for posterior hip and buttock pain.) (See Table 6 for potential risk factors for posterior hip and buttock pain.)

History and Physical Examination

The primary aim for the clinician is to determine anatomical distribution and type of nerve fiber compromised, and the severity of presentation [44]. A careful medical history and physical examination (PE) can identify the specific site of sciatic nerve entrapment complemented by several radiological signs that support the suspected diagnosis. The medical history should include a review of relevant past medical and surgical history, medications, allergies, and associated risk factors for posterior hip and buttock pain. When evaluating a patient with reported hip pain, it is wise to ask the patient to point to where the pain is. With sciatic neuropathy, typically there is a history of total hip arthroplasty [4]. A focused clinical examination of the affected hip with comparison to the contralateral hip is essential. Neurodynamic testing utilizing the straight leg raise is useful [4]. With pudendal neuropathy, there may be associated perineal pain. Palpation of the inferomedial sciatic notch/ischial spine elicits symptoms [4].

The first diagnostic criterion for DGS is tense muscles in the DG area that are extremely pain sensitive. In normal cases, the deep gluteal (DG) area is not particularly pain sensitive, nor tense. Palpation of the parasacrococcygeal region from the back, or with more accuracy from the front, per rectum allow for the proposed diagnostic criteria for DGS. Passive internal and external rotation of the hip and resisted hip abduction and adduction at 90 degrees of hip extension may elicit symptoms [4]. A comprehensive assessment of the hip and lumbar spine can help to recognize the specific problem in each individual case [14]. (For a list of specific evaluation questions about posterior hip and buttock pain, see Table 7). Using specific tests and spine imaging to rule out lumbar spine pathology, the focus of the physical examination should shift toward considering the deep gluteal space as a cause of posterior pain [14].

Laboratory Testing

A complete blood count (CBC) and inflammatory markers (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration) may be helpful for a suspected infectious etiology of posterior hip and buttock pain.

Diagnostic Imaging

a. Plain film radiographs of the pelvis and hips may suggest a specific cause such as hip pathology, lumbar spine degeneration, sacroiliitis, or a calcified shadow in the pelvic cavity.

b. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most useful imaging tool for the diagnosis of DGS. 3-Tesla MRI provides high resolution pelvic imaging and offers visualization of deep gluteal structures and the sciatic nerve with identification of underlying pathology in the deep gluteal space (i.e., entrapped sciatic nerve, compressive fibrous bands, and pathological muscle changes) [14]. Imaging findings include narrowing or loss of joint space, surrounding reactive bony sclerosis and osteophyte formation [4,45].

c. MR Neurography (MRN) using a fluid-sensitive fat-suppressed T2 weighted sequence and T1 weighted sequence evaluates the fascicles and the peripheral nerve itself both of which encompass abundant fat. Normal nerves show intermediateto- minimal hyperintensity on T2-weighted images and have a fascicular pattern, while neuropathic nerves have an abnormally increased T2-signal intensity, similar to that of the vessels. T1-weighted images evaluate the course of the nerve, its caliber, fascicular pattern and size, and presence of space-occupying lesions along the nerve, whereas axial fatsuppressed T2-weighted images assess signal intensity and fascicular shape [5]. Performed in the sagittal plane, with T1- or intermediate-weighted sequences without fat suppression, MR neurography also detects aberrant anatomy of the sciatic nerve [5]. Denervation-induced muscle signal intensity changes can indicate the presence of neuropathy and aid in determining the chronicity or level of nerve pathology [5]. Use of advanced (MRN) techniques when combined with surgical endoscopic correlation has increased awareness of the anatomy and pathologic conditions of the deep gluteal space.

d. Electrodiagnostic testing is useful in excluding lumbosacral radiculopathy as a cause.

Treatment Options

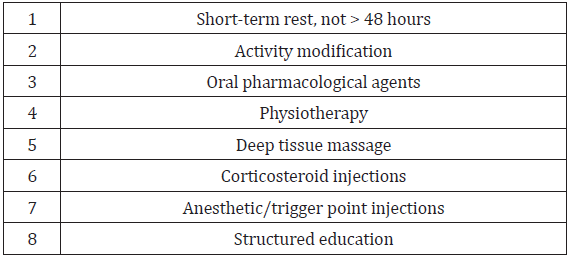

Nonsurgical Options: The main goals for optimal management of DGS involve multidisciplinary treatment and should include, [3] short-term rest (not more than 48 hours) and activity modification, [4] oral pharmacological agents [5] physiotherapy for a 6 week period [46] deep tissue massage [47] corticosteroid injections (CSI) and [14] anesthetic/trigger point injections [5,18,13]. Implementation of a structured and tailored educational program targeted to avoid certain provoking positions such as avoidance of prolonged cross-legged sitting or internal rotation of the hips [5]and factors that increase or decrease the pain can dictate the diagnostic approach and is an important element of conservative management [25]. Oral medication may include both nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) and neuropathic agents such as gabapentin and pregabalin, and muscle relaxants [5]. Physiotherapy should include heat, muscle stimulation, soft tissue mobilization, stretching and strengthening exercises, and aerobic conditioning [46]. If palpation in the gluteal muscles reveals taut bands leading to suspicion of myofascial pain syndrome, trigger point injection or massage can be used [47]. Diagnostic and therapeutic local anesthetic injections can be performed using anatomical landmarks or under ultrasound (US), CT scan or MRI guidance [5]. (See Table 8 for nonsurgical treatment options for DGS.)

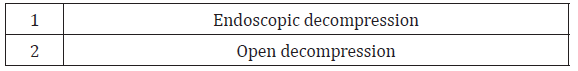

Surgical Options: Surgical treatment for DGS is reserved for recalcitrant cases that have failed optimal conservative treatment options, and functional outcomes following surgery are generally good [42,48]. Surgical procedures are dependent on underlying pathology and generally reserved for those with more severe or recurring symptoms. If patients present with lesions that are suspect to cause a mass effect (i.e., development of hematoma, lipoma and heterotopic ossifications), patients may be indicated for surgery without preoperative conservative management [5]. The criteria for surgical intervention in refractory cases are ambiguous and imprecise [5]. What is clear, however, is that when planning surgery, it is important to understand and consider the underlying pathological conditions. Surgical procedures in DGS focus on exploration of the sciatic nerve regardless of the etiology of DGS [49]. Both endoscopic decompression and open decompression of the nerve are surgical options available depending on degree of adherence of the sciatic nerve and the surgical skill of the surgeon [8,16,22].

Endoscopic decompression of the sciatic nerve is useful in improving function and diminishing posterior hip and buttock pain in sciatic nerve entrapments within the subgluteal space [22]. The prognosis for postoperative outcomes in individuals undergoing endoscopic and open procedures is good [5,48]. Endoscopic decompression (neural release) is an effective minimally invasive approach for DGS and is generally preferred over open decompression because it provides fewer complications [8,16]. Limitations to endoscopic treatment include requiring experienced surgeons who possess a high level of knowledge and skill about the deep gluteal space [8,11,16,25]. In addition, there may be difficult release using the endoscopic technique with a severely adherent sciatic nerve [8,16,22]. (See Table 9 for surgical treatment options for DGS.)

Although the term piriformis syndrome is still commonly designated to describe symptoms related to the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve, newer observations of hip kinematics lead to a more informed term deep gluteal syndrome (DGS) which better distinguishes the underlying pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. While attributing sciatic nerve irritation to the anatomic relationship between the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve, where the latter passes through the greater sciatic notch, DGS describes more. DGS has been associated with radicular type pain related to nondiscogenic sciatic nerve entrapment in other structures within the subgluteal space. The radicular symptoms, historically and singularly attributed to abnormal pathology in the piriformis muscle, are multifactorial and encompass DSG [11]. A level of understanding of the potential exogenous causes of DGS, including hip anatomy, and biomechanics and pelvic kinetics, and sciatic nerve anatomy are important considerations in understanding the mechanics of DGS.

This level of understanding differentiates experts in diagnosis and treatment of DGS from less expert medical providers. Knowledge of all the contributing factors of DGS, focusing on the specific skills of the examination, utilizing appropriate imaging and diagnostic testing, and being the aware of the different treatment options separates and defines those who are usually the most skilled in the diagnosis and treatment of nondiscogenic sciatic nerve pathology associated with DGS [11,50].

Often mislabeled or misdiagnosed due to lack of definitive diagnostic criteria, it is worthwhile to consider DGS as a significant cause of posterior hip and buttock pain. A diagnosis related to lumbosacral spine pathology when the deep gluteal structures are the cause of the pain etiology is common. Thus, diagnosing DGS in a methodical and reasonable approach utilizing MR imaging as a cornerstone diagnostic aid is key to accurate diagnosis. Delay and mismanagement can worsen prognosis due to progression of recalcitrant symptoms leading to burdensome and ongoing intolerable pain and disability. Recommended conservative measures, including rest, activity modification, medication, various therapeutic modalities, and targeted education are essential to alleviate pain and improve functional outcomes. For those refractory to optimal nonsurgical treatment options, surgical options involving decompression of the sciatic or pudendal nerves may be available in patients with severe symptoms to treat specific dependent underlying pathology.

For more Articles on: https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/