An Introduction to Bioactivity of Fucoidan

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

BJSTR is a multidisciplinary, scholarly Open Access publisher focused on Genetic, Biomedical and Remedial missions in relation with Technical Knowledge as well. Our BJSTR maintains a scrupulous, methodical, fair peer review System. Besides, quality control is riveted in each step of the publication process.

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

Introduction

In the clinical context, assessment involves a complex process including a variety of measurement techniques, with primary reliance on observation of performance, and integration of diverse information in a summary judgment. Also, more often than not it involves (formal) testing. Measurement error, hence, lack of reliability, is inevitable when testing takes place. However, when the amount of error is substantial, the inferences drawn from the resulting scores have to be treated with caution or disregarded altogether.

The Classical True Score Theory (CTT), which is one of many measurement theories (e.g. Generalizability Theory, Item-Response Theory), is able to estimate the amount of the existing error [1]. In this context, reliability can be defined as the degree to which the scores are consistent or repeatable, the observed score is free of random/ systematic measurement error, or the extent to which the observed score matches the true score. This hypothetical true ability (score) of the person is difficult if not impossible to capture via any assessment tool due to measurement error. Conceptually, one way of estimating this score would be by taking the mean of many trials performed by the same individual, under the same circumstances, and on the same test. Unfortunately, in the clinical context this method is impractical. Thus, according to CTT, if the amount of measurement error is small one can be confident that the emerging observed score at the very least approximates well the true ability of the person. The degree of this confidence can be wagered based on the magnitude of the reliability coefficient which is often derived via test-retest or internal consistency approaches. The former infers the consistency/stability of repeated performances that are separated in time and measured by the same examiner under the same conditions, whereas internal consistency assesses how well the items of a test or instrument measure a specific construct [2]. If the individual items within a set of tasks are highly correlated that would indicate that the items represent the same construct.

For clinicians, the choice of a particular test depends on many factors such as its purpose, population of interest, theoretical framework and its psychometric properties [3]. For decades Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC) [4] has been considered as a gold standard in the area of adapted physical activity as related to the assessment of children with non-congenital, developmental coordination problems. This is a standardized, norm-referenced test which is used for the purpose of screening, identifying and diagnosing mild to moderate movement problems in children. The test is composed of tasks pertaining to manual dexterity, ball skills, and balance skills. The scores are then accumulated into the Total Impairment Score (TIS), which reflects the overall motor proficiency of a child. Recently, a revised version of MABC has been released (Movement Assessment Battery for Children-Second Edition) [5].

The “kit is easier to carry, the performance test items are more engaging for children, and the scoring system for both the performance test and checklist are more user-friendly” (p. 92). Also, the new version encompasses a broader age range (3 to 17 years of age) than the previous test (4 to 12 years of age), and the number of age bands has been reduced from four to three (3 to 7; 7 to 10 and 11 to 17), resulting in different number of items and new equipment. In regard to age band 2, which is off primary interest here, in the manual dexterity subsection, the placing pegs task now has a new starting position and layout. The lacing board is longer for the threading lace activity, and the shape of the drawing trail has changed. For the aiming and catching section, the beanbag task a box was replaced with a target, whereas in the balance subsection floor mats were added for the one leg hopping activity (Figure 1).

figure 1: The changes between the original and new version of MABC (2 edition), as indicated by the arrow, to lacing the board task (top left), bean beg throw (top right), jumping in squares (bottom left) and drawing tasks.

Despite these numerous changes, the authors maintained that the research pertaining to the reliability and validity of the original tool applies to the new version. Some researchers [6] in the field remained skeptical in regard to this assumption and called for more investigations examining the psychometric properties of the new version. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine different facets of reliability (test-retest & internal consistency) of the age band 2 (7 to 10 years old) for the three subsections and composite score.

Forty participants (18 males and 22 females) between 7 and 10 years of age (M = 9 years, 2 months, SD = 1 year, 3 months) were recruited. In order to be included in this study, children were required to be typically functioning in terms of their motor and cognitive status, as reported by the parents/guardians when completing the DCDQ. The child had to obtain a score higher than 60. Purposive sampling was implemented. The children were recruited from local elementary schools with the permission of the respective school boards in the region. Prior to the data collection, participants were given a brief description of the study. The parents of all participants provided a written consent to take part in this research project prior to its initiation.

Participants attended two sessions, one to two weeks apart. Children were assessed individually and each session took approximately 45 minutes to one hour. At the second testing session, the child was re-assessed at the same location, under the same conditions, and by the same examiner. There are 8 different tasks in the MABC-2 test for age band 2 [5] which are divided into three sub-sections; manual dexterity, ball skills and balance. The tasks within each section are safe, relatively simple and resemble activities that a child performs on a daily basis. There are 3 manual dexterity tasks (placing pegs, threading lace, drawing trail), 2 ball skills tasks (catching with two hands, throwing beanbags onto a mat), and 3 balance tasks (one board balance, walking heel-to-toe, hopping on mats). For each child, a Total Test Score (TTS) and three sub-section scores were derived and converted to standard scores.

The reliability of the MABC-2 was analyzed using ICC correlation coefficient [7] for the test-retest approach. A two-way mixed model with absolute agreement was implemented for the calculation of ICC. An analysis of variance (dependent samples t-tests) was also implemented to determine if there were statistically significant differences between the group means across the two sessions. Cronbach alpha was used to infer the internal consistency of the items across manual dexterity, aiming and catching, and balance subsections. In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha with items deleted was implemented [8]. This procedure allows inferring if the internal consistency of the sub-component improves when a certain item is removed. If so, this would indicate that that specific task is not measuring the same domain as the remaining items. If the Cronbach’s alpha remains the same or decreases, while the item is deleted, this indicates that the item enhances the internal consistency of the sub-component.

In regard to the Total Test Score, the analysis revealed a moderate degree of consistency as inferred from ICC coefficient (0.67). The additional analysis of variance (t-test) confirmed these inconsistencies as scores at time one (M =10.55, SD = 2.49) were significantly different as compared to time two (M = 11.53, SD = 2.53) (t (39) = -2.53, p < 0.05). The analysis of the Sub-Component Scores showed a similar scenario. The analysis of the manual dexterity revealed an ICC = .68, which was supported by the t-tests as statistically significant difference between time one (M = 9.85, SD = 3.10) and time two (M = 10.70, SD = 3.32) (t (39) = -2.14, p < 0.05) emerged. The aiming and catching sub-component also revealed a moderate degree of reliability (ICC = .65), however no differences were found between time one (M = 9.95, SD = 2.31) and two (M = 10.13, SD = 2.54) (t (39) = -0.54, p = 0.59). In regard to balance domain once again a questionable degree of consistency emerged (ICC = .66), which was accompanied by significant differences between the two sessions (M = 11.55, SD = 2.57 vs. M = 14.10, SD = 2.18) (t (39) = -2.09, p < 0.05).

The review of the corresponding scatterplots (Figure 2) demonstrated that across the four scores, the data set was homoscedastic, hence equally distributed along the hypothetical line of best fit. Also, there were no outliers which often affect the magnitude of the emerging coefficient. However, it is also important to note that all the scatterplots showed less than forty data points. This indicates that some children achieved the same scores across the sessions and this could be possible attributed to floor or ceiling effects, hence tasks/items being too easy or too difficult. Likely, larger amount of variability would be more desirable to prevent the potential for restricted range across all the scores.

The internal consistency of manual dexterity, aiming and catching, and balance was inferred from item standard scores, from the second testing session of the MABC-2. The analysis of Manual Dexterity revealed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.61, representing questionable internal consistency for this sub-component. Further analysis was implemented using Cronbach’s alpha with items deleted. As the coefficient did not increase when any of the three items were deleted, this indicated that not one specific task jeopardized the internal consistency of this set of items. The Aiming and Catching sub-scores showed a similar pattern of results as the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.49, once again indicating a questionable internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha with items deleted could not be calculated as there are only two tasks within this sub-section. As it was the case with the two previous sub-scores, the Cronbach alpha for Balance section was also low (0.53) further supporting weak reliability of these items. When items were deleted, the value did not increase for any of the three items, thus once again indicating that not one specific item caused the questionable internal consistency.

The analysis of the TTS revealed an ICC of 0.67 when test retest reliability was examined, thus indicating a questionable degree of reliability. As the use of correlations alone can be problematic to assess the degree of systematic bias, particularly when the inter-individual variability is low, the analysis of variance was also carried out. In line with the correlation, the data showed significant differences between time one and time two. In fact, only 9 out of the 40 participants achieved the same standard score across the two trials (Figure 2, top graph). This indicated that there is a lack of consistency across performances in more than three quarters of the individuals. To date, there has been only one study which examined the reliability of the age band 2. Holm and colleagues [9] examined intra- and inter-rater reliability based on component scores and reported ICC values of 0.68 and 0.62, respectively. These findings are similar to those reported here. The sample size and characteristics of the participants were also comparable between the studies. Thus, the emerging results appear to be robust even though different reliability coefficients were examined. In terms of the research examining the test re-test reliability based on the original version of MABC, Chow and Henderson [10] found that the TTS had a higher, but still moderate reliability (0.77). However, their sample size was also larger (75 participants), and the study was conducted on age band 1 (4 to 6 years). Also, the authors did not indicate which type of score was used (standard, component, or percentile) for the calculation of ICC, thus a caution is warranted when comparing the results from the two studies.

figure 2: Intra-class correlation coefficients and respective scatterplots for standard scores for total test score (top figure), aiming and catching (second from the top), balance (third from the top) and manual dexterity.

The degree of reliability of the three sub-components was in line with the findings pertaining to TTS. Manual dexterity revealed the ICC of 0.68, which once again indicated poor reliability. This lack of consistency was also supported by the analysis of variance, which showed that there were statistically significant differences between the two testing sessions. The analysis of the individual data across both sessions also showed that 25 of the 40 participants scored higher on time two suggesting that some systematic and/or random bias emerged. The standard deviation also increased between the sessions indicating that as the group the sample was more variable despite that they were assessed with the same tool for the second time. In terms of previous research, the present values are similar to those reported in the past studies. Holm and colleagues [9] showed that age band 2 had ICC values of 0.62 (intra-rater) and 0.63 (inter-rater) for the manual dexterity sub-component. However, the reliability of this subsection in other age bands was substantially higher. Ellinoudis and colleagues [11] revealed an ICC of 0.82 and Wuang and colleagues [12] reported an ICC of 0.97 for the test re-test reliability, for age band 1. No studies were conducted on age band 3, or the original MABC, that examined the test re-test reliability for manual dexterity.

In terms of aiming and catching, the ICC for the test re-test reliability was 0.65, thus once again indicating a questionable consistency. The analysis of variance showed that there were no statistically significant differences between time and time two. Nevertheless, the individual data showed that only 9 of the 40 participants had the same standard score across both testing occasions, thus from the standpoint of absolute reliability little consistency was evident. The present results are to some extend comparable to those reported by Holm and colleagues [9] who showed that the ICC values ranged between 0.49 and 0.77 for intra- and inter-rater reliability, respectively. In regard to previous research, with other age bands, similar results (ICC = .61) were reported by Ellinoudis and colleagues [11] despite the fact that their sample was much larger than the current data set. This pattern of results may indicate that this subsection of the test as a whole represents an issue in the revised edition of the test [13].

The analysis of the balance sub-component also revealed a questionable degree of reliability. This could be due to the fact that tasks such as one-board balance were too challenging to most of the children. In fact, 50% of participants achieved the same score across trials, in comparison to the other two sub-components and the TTS. Thus, the individuals were scoring consistently but poorly across the both sessions, leading to small intra-group variability. The low reliability found here is consistent with the coefficients (.49 & .29) reported in previous research, for age band 2 [9]. The authors of that research also supported the notion that low ICC values for this subsection may be due to the difficulty associated with one board balance task. In regard to other research, Ellinoudis and colleagues [11] reported an ICC value of 0.75 for age band 1.

However, it should be noted that the nature of the tasks included is different across the age bands. For example, in age band 1 the participants are required to complete 3 tasks including one leg balance, walking with heels raised and jumping on mats. Although the latter two items are comparable to those in age band 2, the one leg balance task would be considerably easier than the one-board balance task. Therefore, this task likely contributed to a restricted range in age band 2.

The Cronbach’s alpha for manual dexterity was 0.61 indicating a questionable reliability. The low internal consistency could be due to the fact that one of the three items is not measuring the construct of interest, therefore lowering alpha. For example, the placing pegs and threading lace task are very similar in that they are both timed tasks. However, the drawing trail-2 task is selfpaced and it requires effective use of a pen/pencil. Thus, although similar, the additional constraint of time and use of an implement may require different aspects of motor functioning. A low alpha could also be attributed to the fact that there are only three tasks within the manual dexterity sub-component, as Cronbach’s alpha is higher when there are more test items. Wuang and colleagues [12] examined the internal consistency of age band 1 and reported a much higher Cronbach’s alpha (0.81). However, in that study the age range was larger (6 to 12 years of age), as was the number of the items examined. The manual dexterity subsection examined here had three items whereas the previous research combined items from each age group resulting in 9 scores.

The present study revealed that aiming and catching subsection had the lowest reliability as evident from Cronbach’s alpha of 0.49. This is not surprising. There are only two tasks included in the section, and they differed considerably in terms of their characteristics. Catching with two hands involves interceptive skills whereas throwing a bean bag on to a mat is an accuracy type of the task, without external time demands. Thus, although both involve goal-directed manual actions they do not belong to the same domain such as ball skills. In regards to previous research, Ellinoudis and colleagues [11] found the internal consistency of age band 1 to be acceptable with an alpha of 0.70, thus it is possible that the number of tasks as well as their different perceptuo-motor constraints resulted in such low degree of consistency.

The analysis of the internal consistency for the balance subcomponent revealed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.53 thus once again indicating that the three items may not be measuring the same domain. When examining the results of Cronbach’s alpha with items deleted it was evident that when each task was individually removed, the alpha decreased. The walking on a line and hopping on mats tasks, although also completed on one foot, revealed a much higher scores when compared to the one-board balance task. In fact, the individual data revealed that the one board balance task was the most difficult, while the remaining two (walking on a line and hopping on mats) proved to be too easy as almost all children had a perfect score. In terms of the previous research, Ellinoudis and colleagues [11] also reported a relatively low Cronbach’s alpha (0.66) for the balance sub-component of age band 1. In contrast, Wuang et al. [12] reported the highest internal consistency for balance with an alpha of 0.84. However, as previously mentioned, the findings from that study are difficult to compare to the present results due to differences in the age of participants and number of items.

Collectively, the reliability coefficients derived from this study ranged between low to moderate, across test-retest approach and internal consistency values. Although the existing research on this age band is limited, it is in line with the present findings. Also, in regard to the reliability of the original version of MABC it is evident that the reliability of the new version is not enhanced, in fact it is lower across the different scores [14,15]. In the present study the reliability of manual dexterity, even if did not meet the expected level, was the highest. The reliability of aiming and catching as well as balance was lower, even if not substantially. In the case of the former section the lower reliability coefficient may be due to the fact that the aiming and catching is comprised of only two tasks (two handed catch & throwing a bean bag on to a target). The reliability of balance sub-component was uniformly least consistent as evident from the weakest ICC values and the lowest internal consistency. At the individual item level of analysis, this could be attributed to the fact that one board balance task proved to be too difficult whereas the hopping on mats and walking heel to toe were too easy. The resulting celling and/or floor effects have an impact on variability, thus the correlations. However, this also indicates that both tasks are not able to differentiate between “good” versus “bad” movement proficiency resulting once again in invalid inferences. Likely these items require further validation, and warrant caution when used in the clinical setting to examine the balance proficiency of children with movement problems.

Aside from the psychometric nomenclature, what does it mean for a clinician if a score or a test lack reliability? Broadly speaking, this indicates that if a person was to be retested again, under the very same environmental constraints and with the same/similar status of individual characteristics, the emerging score would be different. According to the Classical True Score Theory [1], if a person was in fact to be tested over and over again, the mean of these attempts would somewhat accurately approximate the true ability of the person. However, for the clinical practitioners and researchers alike, this approach is not practical for various reasons. Aside from the rather pragmatic issue of time demands, as well as the availability of the participants, the scores could change due to learning effect alone as the person may enhance his/her skills due to familiarity with the tasks acquired over repeated administrations. Also, if the time period between the testing sessions is prolonged, the maturation effect may influence the score, which is particularly relevant when working with children and examining constructs which do change/develop over time (e.g., perceptuo-motor status). Thus, as it stands the most effective way of dealing with measurement error is becoming aware of its potential sources and understanding the degree to which it may affect the assessment/ testing process in regard to its goals/purposes.

From the clinical perspective, in the context of atypically functioning youth, formal assessment is carried out in order to screen the child to determine the need or eligibility for the clinical placement or to diagnose explicitly the underlying condition. Lack of reliability in the tools used, formal or informal, may lead to false positive or negative inferences, which in turn may have detrimental consequences for those involved. Hence, if the obtained score does not approximate well the true ability of the child due to error, it may prevent the child from entering a particular program or resources, or vice-versa it may place the child in the clinical setting when no rehabilitation is in fact required. Another important purpose of assessment in the clinical setting is to determine the potential progress of the child, implicitly the effectiveness of the program implemented. As in the previous point, lack of the reliability may lead to erroneous/invalid inferences. If the observed score does fluctuate as a result of the error, the potential differences may be attributed to real or meaningful changes due to treatment, once again leading to false positive inferences. Collectively, as evident questionable reliability represents an important issue in the assessment.

In regard to age band 2, of MABC-Second edition, the teachers, clinicians, and researchers should implement this test with caution. To address the emerging (psychometric) issues the child may be retested twice, in the same context, however the learning and maturation effects need to be kept in mind. Also, the assessor should be formally trained and provided with extensive experience when using this test. This may not be an issue with simple informal tests, but it may be a case when a more complex assessment tool, such as MABC-2, is used. Another potential solution, in the case when the lack of reliability is suspected, maybe a triangulation of the different resources in order to confirm with certainty the current status of the child, hence his/her true skill level. In perceptuo-motor domain, as related to assessment of children with developmental deficits, the implementation of additional tests such as TGMD [16] or Bruininks [17,18] may be considered. However, even so it should be kept in mind that different tests operationalize the construct of movement proficiency differently, have varying purposes, and also that their reliability may or may not be optimal at the level of composite scores, sub-scores and/or individual items. Ultimately, as an adapted professional who is implementing different assessment tools to either screen, place or diagnose a child, or a researcher who implements the tests for the purpose of sampling or in an attempt to examine the effectiveness of the program, the issue of reliability has to be of vital importance. As evident from the present analysis of MABC-2 [5], relying on the information provided in the test manual, or anecdotal evidence regarding the “gold-standard” status of the test may negatively influence the validity of the inferences emerging form the tests scores [19].

Potentials for Reducing Cancer Incidence in Nigeria-https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/2021/01/potentials-for-reducing-cancer.html

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

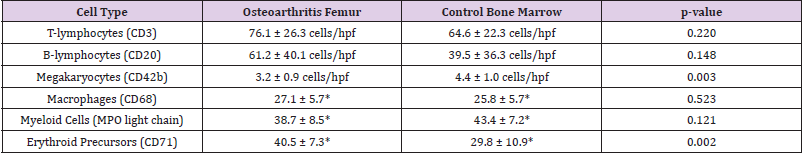

Hematopoietic Elements in Osteoarthritic Femurs Compared to Normal Bone Marrow as Evaluated by Immunohistochemistry Introduction Affecting...