Picky Eating and Nutritional Status among Vietnamese Children Under Five Years of Age in Hue, Central Vietnam

Background

Eating is to meet the essential needs of human beings and to sustain life, growth and development. In every stage of life, a human being will have different energy and nutrient needs. For children, nutrition during the first years of life has important implications for development as well as quality of later life [1]. During growth stages, if essential nutrients are not met, permanent damage to tissues and organs can occur [2]. The most important stage of development is from newborn to five years old. This is the fastest period of weight gain and it is during this time that many organs, particularly and the central nervous and motor systems, become fully functioning. As this is also a period of high nutritional needs and susceptibility to diseases, therefore, children are at greatest risk of malnutrition. Malnutrition not only affects the physical but also mental health of the child and causes severe consequences for society [3]. Improper nutrition is a direct cause of malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies such as vitamin A, iron, iodine, zinc amongst others. In addition, lack of food or inappropriate eating behavior may contribute to dietary inadequacy and is a risk factor for malnutrition [4]. Insufficient food availability is an important cause of undernutrition, while the ability or willingness to consume available foods is another major factor [5].

Picky eating is “the unwillingness to eat familiar foods or try new foods, severe enough to interfere with daily routines to an extent that is problematic to the parent, child, or parent-child relationship” [6]. It is relatively common among infants and children, often causing anxiety for parents and caregivers. Picky eating is often linked to nutritional problems [7] and is also a risk factor for the development of an eating disorder [8]. The prevalence of picky eaters fluctuates, depending on the definition and assessment methods used. Literature reviews indicate that picky eating is prevalent among children, especially in high income countries. Estimated prevalence of picky eaters in high income countries was 21% among children aged 3 - 4 years old in USA by Jacobi C [9]; 19% to 50% among children aged 4 - 24 months old by Carruth [10]; 44.6% among toddlers 12 - 47.9 months old by Klazine van der Horst [11]; 14-17% among pre-schoolers in Canada by Dubois L [12]; 31% in Australia by Rebecca Byrne [13]; 39% of children 12-72 months old in Turkey by Orun E [14]; while Charlotte M Wright (2007) found a much lower prevalence in United Kingdom (8%) [15].

There is some information on picky eating in Asia. The prevalence of picky eating in Singaporean children aged 1-10 years was 49.2% [16] and as high as 54% in Taiwanese children aged 2–4 years [17]. A study implemented in urban areas of China showed that 23.8% of parents considered their infant or toddler to be a picky eater; the prevalence of picky eaters increased significantly with age, from 12.3% at 6-11 months to 21.9% at 12-23 months, and then to 36.1% at 24-35 months (p < 0.001) [18]. Another study in China showed a prevalence of picky eating as high as 54% among pre-schoolers. In Vietnam, studies on picky eating are very limited. Prevalence of picky eating among children under five years of age at the National Hospital of Pediatrics (Hanoi) was 44.9% [19] and 20.8% was reported by a study in Ho Chi Minh City [20]. The prevalence was as high as 54.58% among children from 1 - 6 years old in Ho Chi Minh City [21]. As Vietnam undergoes a transition in nutrition, picky eating is anticipated to become an emerging issue for children when access to stable food supplies are guaranteed. Having a scale to define picky eating in the Vietnamese context is essential not only for the child, parents, caregivers but also for health and educational workers. This study aimed to describe the prevalence and characteristics of picky eating and to explore the relationship between picky eating and nutritional status among children under five years of age living in Hue, central Vietnam.

Methodology

Participants

Children under five year of age living in Hue, central Vietnam and their parents or caregivers.

Methods

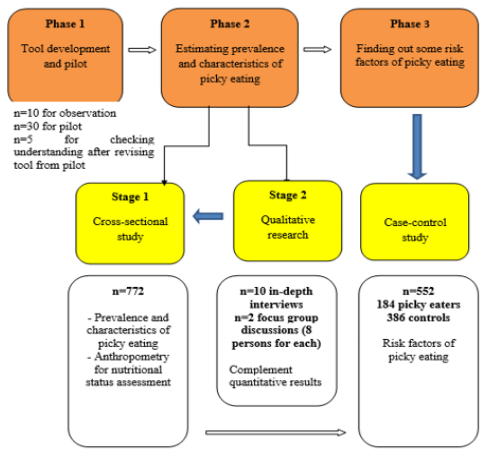

Study Design: The picky eating study was a three phases study in which phase 1 was an explanatory study for developing and piloting the tools. Phase 2 included 2 stages: the first stage was a cross-sectional study aimed to estimate the prevalence and to describe some characteristics of picky eating as well as nutritional status of children, while the second stage was a qualitative research which included 10 in-depth interviews and two focus group discussions aimed to complement quantitative results. Phase 3 was a case-control study aimed to determine risk factors of picky eating. Refer to Figure 1 for the flow chart of the study. The present analysis used data from the baseline measures of stage 1 from phase 2. A cross-sectional study was conducted on a sample size of 772 children under five years of age living in Hue city of central Vietnam. Questionnaires were used for face-to-face interviews with parents or caregivers about child feeding and eating behaviours. Height/length and weight of the child were obtained by trained researchers, following recommendations of the Vietnamese National Institute of Nutrition [22]. Data on height/length and weight of the children was used for nutritional status assessment by applying WHO Anthro software [23].

Sampling Method: The multistage sampling method was used for randomly selecting a sample of 4 out of 27 wards of Hue city. Based on the list of children under 5 years of age given by each commune health center, we calculated the total number of children in all four wards, then calculated the number of children for each ward by probability proportional to size (PPS) technique. In each ward, random sampling was used to choose children for the final sample

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Children were considered for inclusion if they were under 5 years old at the time of the study, were living in the study area at the time of the study and father, mother or caregivers agreed to participate (verbal consent). Children were excluded from the study if they had abnormalities of the mouth that might affect their ability to eat or other special conditions, for example Down syndrome, mental retardation (with medical record); or their father, mother; or caregivers did not agree to participate.

Assessment Criteria

Picky eating: The Picky Eating Scale (PES) had previously been developed after a review of the literature (phase 1) and by observing the main meals of ten Vietnamese children under five years of age, considered to be picky eaters by parents/caregivers living in Hue, Vietnam. Observations occurred at participants’ houses or public places such as parks or food retail outlets between October and November of 2014. The types and amounts of food consumed, as well as the length of each mealtime, eating and playing activities, attitudes and emotions of both the child and feeding person were recorded. All eating activities of children were grouped into three main themes based on the observations and literature: length of time for each meal and eating activities of the children (eating, chewing, holding food); number of meals, diversity and amount of food that the child consumed per day; emotional or behaviours (happy, sad, worried) of the child at mealtime. The Picky Eating Scale (PES) was developed by deploying aspects derived from these three main themes.

The scale had 14 questions, each question was scored based on the level of feeding difficulty, ranging from 0 to 3 points (the higher the score, the greater the picky eating behavior). The scoring from 0 to 3 points based on a previous study implemented in Vietnamese context [24]. In June 2017, two experienced nutrition staff from the Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy conducted a pilot study on 30 parents/caregivers of children under five years of age, using face to face interviewing techniques. Comprehension of the questions was assessed, and questions were reworded to improve understanding. Cronbach’s Alpha value was calculated for testing internal consistency of the PES. Results showed the value for Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.82. PES was based on parent-report and provided a range of scores (0 to 42), with the used as the cut-off point for defining pickiness. As data analysis showed 10.5 as median value, children with a total score above 10.5 were defined as picky eaters.

Assessment of Nutritional Status: WHO Anthro software was used for assessment of nutritional status of children. The threshold for being assessed as undernutrition was <-2SD.

a) Children with weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) of under -2SD would be classified as underweight and under -3SD would be classified as severely underweight

b) Children with length or height-for-age z-score (HAZ) of under -2SD would be classified as stunting and under -3SD would be classified as severely stunted

c) Children with weight-for-length and weight-for-height z-score (WHZ) of under -2SD would be classified as wasting and under -3SD would be classified as severely stunted. Children would be overweight or obese if WHZ was higher than +2SD [23].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Product and Services Solutions, version 20.0). Continuous data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD); ordinal data was reported as numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested for statistical significance using Fisher’s exact 2-tailed tests or 2-tailed t tests for independent samples as appropriate. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The aims of the research were explained to all parents or caregivers. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interview, with participants signing the interview paper at the completion of the interview. For the qualitative component, attendants were asked to give permission prior to recording. All procedures were approved by the Committee for assessment of PhD proposal, Faculty of Public Health, Hue College of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hue University.

Results

Characteristics of Children and Interviewees (Parents/ Caregivers)

The study consisted of 772 children with a mean age of 34.2 ± 15.5 months. Half (50.8%) of the children were male and 79.1% were the first or second child of the family. As there were some families with more than one child in the study, only 716 parents or caregivers were interviewed. The mean age of interviewees was 37.5 ± 12.2 years old, 67.6% of them were mothers. Of the interviewees, 76.6% of had a level of education of secondary school and above, however, 2.2% of were illiteracy. The poor and the near poor accounted for 4.7% of the households.

Picky Eating and Nutritional Status of Children

Picky Eating

Prevalence of Picky Eaters: Prevalence of picky eaters was 25.3%, the highest prevalence (31.3%) was seen in group of under 24 months old. Prevalence of picky eating among boys and girls was 52.8% and 47.2%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference between genders.

Common Signs of Picky Eating: The most common signs of picky eating were eating less (63.6%), eating slowly, mealtime lasting for over 30 minutes (62.1%), retaining food in the mouth (57.4%), difficulty in feeding the child, pressure eating (45.1%). 11.3% of children cried or had tantrums at mealtimes.

Onset Time of Picky Eating: There were 33.6% and 30.8% of picky eaters had signs at 12-<24 months old and 6-<12 months old, respectively. The prevalence decreased as the child got older with only 2.5% at 48 months and older being classified as picky eaters.

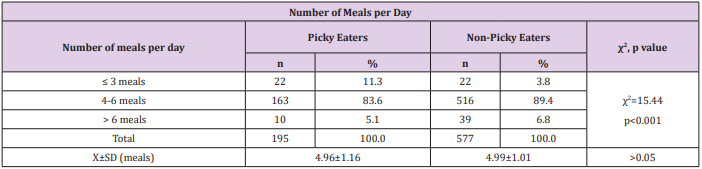

Number of Meals Per Day: Prevalence of picky eaters who ate not more than 3 meals per day (11.3%) was higher than that of nonpicky eaters (3.8%). There was a statistically significant difference regarding the number of meals per day between picky eaters and non-picky eaters (p<0.001) but no statistically significant difference in terms of mean meals (p>0.05) (Table 1).

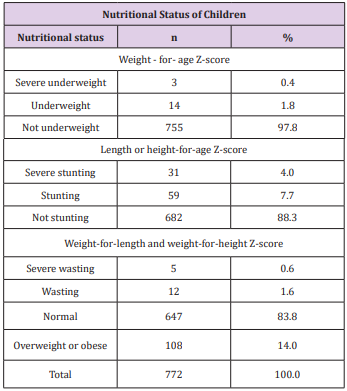

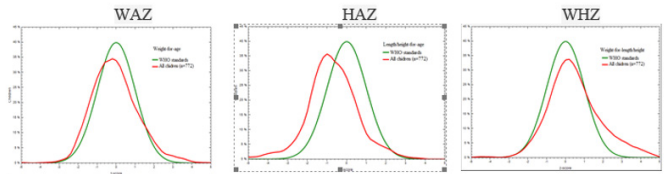

Nutritional Status: The prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting among children was 2.2%, 11.7% and 2.2%, respectively (see Table 2). In general, WAZ, HAZ and WHZ of the sample were lower and smaller compared to WHO Child Growth Standards (see Figure 2).

Relationship between Picky Eating and Nutritional Status: A negative relationship between picky eating and stunting (χ2 = 5.721, p=0.017) and wasting (χ2 =10.428, p=0.005) was found.

Discussion

Picky eating is relatively common among infants and children, often causing anxiety for parents and caregivers. At present, as there is no consistent definition of picky eating, there is no unified and well-defined method of assessment [6]. Several different measures have been developed to assess picky eating, ranging from a simple single question (“Is your child a picky eater?” [10,25]) to more complex multi-item sub-scales in larger questionnaires, generally related to eating behaviours [7,25-28]. Due to different assessment methods, prevalence of picky eating is variable, ranging from 20 to 60% in all children [29]. This study used a scale to define pickiness among Vietnamese children under five years of age. The scale was developed from three themes derived from observations and the scoring of the scale was quite consistent with the study by Huynh Van Son, implemented in the same country [21]. Prevalence of picky eaters in our study was 25.3%, much lower than prevalence’s reported from previous studies with only one question “Is your child a picky eater?” [10,25].

In a study of Hendy, Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (Wardle) was used for interviewing and the mean was used as the cut-off point for defining picky eating [30]. Due to the small sample size and the abnormal distribution of data, we used the median as the cut-off point for defining pickiness. Our study showed a negative relationship between picky eating and HAZ as well as WHZ but no statistical relationship between picky eating and underweight. Picky eaters were more stunted and/or wasted compared to nonpicky eaters. However, information from Figure 2 showed that all three indicators of the studied children were lower than the reference population of the World Health Organization (lower peak and shift to the left, especially HAZ). Prevalence of overweight and obesity by WHZ was quite high (14.0%). Some studies had found picky eating as a risk factor of underweight [12,31,32]. Some studies also showed that at the age of four, picky eaters had lower body mass index (BMI) and were more likely to be underweight than non-picky eaters [12,26,31].

Figure 2: Nutritional status classified by three indicators included WAZ, HAZ and WHZ of the sample compared to WHO Child Growth Standards.

A longitudinal study found that prevalence of underweight among picky eaters was 20.6%, higher than non-picky eaters [12]. Dubois conducted a longitudinal study on 1498 children and found that picky eaters were twice as likely to be at risk of being underweight at the age of 4.5 compared to non-picky eaters [31]. Ekstein Sivan found similar results that children with picky eating habits, especially those younger than 3 years of age, were at increased risk of being underweight. These are significant findings, as being underweight is an important risk factor for poor cognitive development, learning disabilities, long-term behavioural problems, increased prevalence and severity of infection, and high mortality rates [31]. Young Xue conducted a study on growth and development of 937 healthy preschool children in China and reported that picky eating behavior lasting over two years was associated with lower weight for age [32]. The question for the opposite hypothesis was if there was relationship between picky eating and weight gain. Galloway reported that picky eaters were less likely to be overweight. They consumed fewer fruits and vegetables, but also fewer fats and sweets. All girls consumed low amounts of vitamin E, calcium, and magnesium, but more picky girls were at risk for not meeting recommendations for vitamins E and C and also consumed significantly less fiber [26]. In contrast, according to Fisher J O eating a limited amount of fruit and vegetables, but lots of foods with high-fat and energy can increase risk of overweight in picky eaters [33]. Furthermore, evidence is available that picky children may consume more sweetened foods [21], consequently, there is a risk that such children may establish a habit of over-consumption of energy dense, preferable foods, eventually culminating in excessive weight gain.

However, there are no longitudinal data to support this to date [34]. In addition, some studies observed no significant effects of picky eating on growth [15,25]. Paige K Berger conducted a longitudinal study for 10 years on girls’ picky eating in childhood. Results showed that persistent picky eaters were within the normal weight range, were less likely to be overweight, and had similar fruit intakes to those of non-picky eaters [35]. Wright conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from a United Kingdom population-based birth cohort, which included 455 questionnaires completed by parents when their children were aged 30 months. Picky children described by parents were slightly lighter and shorter and had grown less well than the remainder, but these differences did not reach significance at the 0.05 level [15]. Picky children consumed fewer micronutrient-rich foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and meats [7] as well as low in vitamin C, vitamin E, fiber and folate foods [26,34], which might result in the risk of undernutrition. However, regardless of whether the child is picky or not, the growth and development of the child’s height is still a matter of controversy. Some studies focused on pre-schoolers with eating problems showed that picky eating had long-term problems associated with growth deficiency [31]. Other studies showed that pre-schoolers with picky behaviours were more likely to be underweight, were less likely to be overweight and were associated with an inadequate/suboptimal intake of essential nutrients [12,26].

Conclusion

Picky eaters were relatively prevalent among Vietnamese children under five years of age. Picky eaters were more stunted and/or wasted compared to non-picky eaters.

Conflicts of Interest

This study has identified a scale for defining picky eating in children under five. However, further studies should be conducted to test the application of the scale. This study also found some characteristics of picky eating and its relationship to nutritional status. Identifying and understanding picky eating amongst children is valuable for parents, caregivers and health workers in order to create awareness regarding other aspects to prevent undernutrition.

Funding Statement

This work is a part of PhD. research of the first author at Hue College of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hue University, Vietnam and receives no funding from any organization.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our sincere thanks to all the participants involved in the study, especially the children and their caregivers for their coordination and support when conducting research.

More BJSTR Articles: https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.