Why It Is Important to Recognize Brugada Syndrome: A Case Report and Literature Review

Introduction

In 1992, R. Brugada and J. Brugada were the first to describe a syndrome characterized by right-bundle branch block (RBBB) with ST segment elevation followed by an inverted T-wave in the right precordial leads, which predisposes apparently healthy subjects to Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD). This syndrome was later named after its discoverers [1-3]. Since then, numerous scientific and clinical studies have been conducted in order to clarify pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and diagnostic criteria for this syndrome as well as methods for sudden death risk assessment and treatment methods. It is important to know that other diseases such as acute Myocardial Infarction (MI), arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, or typical RBBB can be mistaken as the Brugada pattern.

Presentation of Case

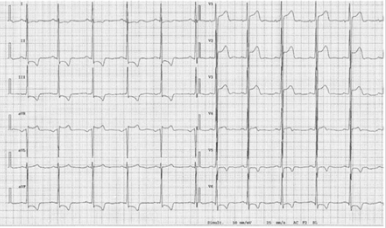

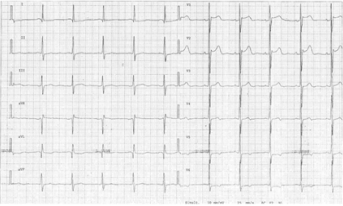

A 30-year-old male patient with no previous cardiac problems and complaints visited a family physician for a preventive health examination. An Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed J-point elevation and ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (Figure 1). Acute Myocardial Infarction was suspected, and the patient was urgently referred to the hospital. The troponin I level in serum showed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the heart revealed no structural or functional heart abnormalities. The patient was consulted by a cardiologist. As the collected data were insufficient to confirm the diagnosis of MI, Brugada Syndrome (BrS) was suspected. Data of the patient’s family members who had had an ECG at some point in their lives were also recorded. The ECG of the patient’s mother also showed abnormalities consistent with a BrS ECG pattern (Figure 2). A family his- tory showed no episodes of sudden death, faint, seizures, or other symptoms that might suggest an abnormal ventricular rhythm.

Figure 2: ECG of patient’s mother. J-point elevation and ST-segment elevation are observed in leads V1-V3; abnormalities are more prominent in lead V2.

The patient and his mother underwent Holter monitoring, and no arrhythmias were observed. It was decided that abnormalities observed on patient’s and his mother’s ECGs were characteristic of the Brugada pattern and that they mimicked ECG abnormalities typical for acute MI. The patient was explained potential BrS complications. As neither the family members nor the patient had clinical manifestations characteristic of BrS, no provocative drug challenge was performed. The patient was advised to avoid febrile episodes and, if they occur, to use aggressive treatment with antipyretics, such as aspirin and paracetamol, and cold. Also, he was suggested to avoid hypokalemia, carbohydrate-rich meals, alcohol, drugs, and very hot bath.

Discussion

BrS is referred to as an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder; however, it can be sporadic in some patients, i.e., not found in other family members or relatives [2]. In 1998, the first BrS-related mutation in the SCN5A gene encoding for the α-subunit of the cardiac sodium channel was identified [1]. To date, more than 500 mutations of this gene have been linked to BrS. Mutations of this gene are found in around 30% of patients with BrS. 2-5% of BrS is associated with other gene (CACNA1C, GPD1L, HEY2, PKP2, RANGRF, SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, SLMAP, and TRPM4) [4]. Due to all data only SCN5A genetic analysis is recommended. The mechanism of BrS is not completely understood, although the existing data show that changes in ion channels, caused by gene mutations, disturb transmembrane ion currents in cardio- myocytes, causing transmural voltage gradient and depression of the right ventricular transmural and epicardial repolarization, thereby facilitating development of the reentry-type ventricular arrhythmia [5]. Nademanee et al. suggest hypothesis that the arrhythmogenic features is caused by epicardial surface and interstitial fibrosis in the Right Ventricular Outflow Tract (RVOT) [6].

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms associated with BrS are caused by recurrent ventricular arrhythmia, Ventricular Tachycardia (VT), and Ventricular Fibrillation (VF). They are short-term (lasting only seconds) and disappear naturally. Some patients may be asymptomatic for their life, or symptoms of the disease may include palpitation episodes, syncope, nocturnal agonal respiration, seizures, agitation, loss of bladder control and short-term amnesia (probably due to brain hypoxia) [5,7]. Prolonged VT may resolve into VF and cause cardiac arrest. VF and SCD can be initial clinical manifestations. It has been reported that BrS is more prevalent in South-East Asia including Japan (present in 15/10,000 inhabitants) com- pared with Western countries (2/10,000) [5,8]. BrS episodes occur more frequently in men, and the risk of SCD in men is 5.5 times greater than in women. The mean age of patients with BrS is 41 ± 15 years, although first symptoms might present in childhood.

These age-related differences can be explained by hormonal changes - men with BrS have higher concentration of testosterone [4]. Arrhythmias are observed both when the patient is at rest or sleeping, usually between midnight and 6 am, but are rare in the evening and extremely rare during the daytime [9]. Supraventricular arrhythmia may be observed in BrS patients, and the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in patients with BrS is 10%–20%. It indicates disease severity and higher risk of VF [10]. BrS is also known as one of the causes of sudden infant death or SCD in young children [1]. BrS causes up to 4% of all SCD and at least 20% of SCD in patients with a structurally normal heart [11].

Diagnosis

Electrocardiography is the main diagnostic method for BrS. In 2012 expert consensus document was published which indicates 2 ECG abnormalities for BrS:

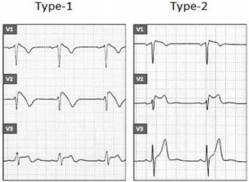

a) Type 1, also known as a “coved type,” is characterized by an ST-segment elevation ≥ 2 mm in one or more right precordial lead (V1-V3) followed by a negative T wave or isoelectric line approaching to the symmetrical T wave.

b) Type 2, also known as a “saddle-back” type, is characterized by an ST-segment elevation ≥ 0,5 mm in one or more right precordial lead (V1-V3) with convex ST. T wave is positive or biphasic [12] (Figure 3).

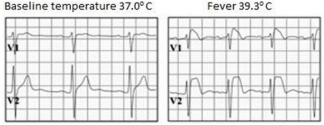

Type 1 or coved type ECG is considered as the only diagnostic pattern for BrS while type 2 only suggests BrS diagnosis. These ECG patterns may be observed in more than one right precordial lead (V1-V3) registered at the fourth, third, or second intercostal spaces. Dynamic variability is characteristic of an ECG in patients with BrS: an ECG could be normal at one time, and at another time point, the type 1 ECG pattern may be observed. Influence of vagal activity (slow heart rate, postprandial status, night-time) and fever (Figure 4) tend to enhance the J-point and ST-segment elevation and type 1 pattern, while physical exercise and catecholamines have a reverse effect [1,5]. According to Mizusawa et al study patients with a fever induced type 1 ECG have an intermediate risk for SCD [13]. Diagnostic test with a sodium-channel blocking agent should be executed when there is clinical signs of BrS (type 2 ECG, family history of BrS, syncope, aborted sudden death) without type 1 ECG pattern. According to literature many patients with type 1 ECG pattern are asymptomatic. Based on this statement in 2012 experts changed BrS diagnostic criteria: “BrS is diagnosed when a type 1 ST elevation is observed either spontaneously or after intravenous administration of a sodium channel blocker in at least one right precordial lead (V1 and V2), placed in a standard or superior position (up to the 2nd intercostal space)” without further tests [12].

It should be noted that some conditions may cause BrS-like ECG abnormalities (Figure 5); therefore, it is important to distinguish BrS from atypical RBBB, acute MI (especially MI of the right ventricle), acute pericarditis and myopericarditis, hemopericardium, pulmonary embolism, dissecting aortic aneurism, left ventricular hypertrophy, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle, mechanical compression of the right ventricular outgoing tract, mediastinal tumor, pectus excavatum, status after electrical cardioversion, early repolarization (especially in athletes) and hypothermia. Similar ECG changes could also be caused by hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, cocaine and alcohol intoxication and medications such as antiarrhythmic (Class IA and Class IC sodium channel blockers, calcium channel blockers, β-adrenoreceptor blockers), antianginal (calcium channel blockers, nitrates), and psychotropic (tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, lithium) [2,5].

Figure 5: Comparison of the ECG pattern in type 1 and type 2 BrS and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ADRV), pectus excavatum, athletes, and partial RBBB.

Management

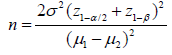

The main BrS treatment options are Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) or drug therapy (Quinidine). The ICD shall be implanted in all symptomatic patient [3,12,14]. Hevia et al. [15] study showed result that 62,5% of patients with type 1 ECG pattern and ICD received an appropriate shock during the follow-up [15]. The management of asymptomatic patients remains a controversial topic, and the opinion of different authors on this issue differs. In the FINGER study, the multivariate analysis revealed that neither spontaneous type 1 ECG nor positive electrophysiological studies were predictive of arrhythmic outcomes (P=0.38 and P=0.09, respectively). The overall event rate for asymptomatic patients was low (0.5% per year) [16]. A low rate of an arrhythmic event among asymptomatic patients who had ST-segment eleva- tion only after drug challenge was also noted in the study by Priori et al. which enrolled 200 patients [17].

Cardiac events that occurred between birth and the last followup (i.e., a mean observation time of 41 years) were evaluated in this cohort of patients, and cardiac arrest was documented in 22 indi- viduals (20 men and 2 women). Nevertheless 2012-year consensus recommends producing electrophysiological tests for asymptomatic patients, especially those with the spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern, and asses the need for an ICD. Ablation is another alternative treatment for BrS. Nademanee with colleagues followed-up 9 symptomatic patients with coved type ECG pattern and performed catheter ablation over arrhythmogenic area. 8 of 9 patients showed normalization of the ECG pattern and a significant suppression of inducible Ventricular Tachycardia or Ventricular Fibrillation. Furthermore for 2 years follow up after catheter ablation no recurrent VT or VF episodes were noticed [18].

Conclusion

Due to seriousness of symptoms, manifesting in case of Brugada syndrome, a prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of this channelopathy is of great importance. However, physicians should be aware of overdiagnosis of Brugada syndrome as a Brugada ECG pattern can be seen in other clinical conditions. ICD is recommended for all symptomatic patient and the management of asymptomatic individuals remains controversial.

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient for giving us permission to present this clinical case.

More BJSTR Articles: https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.