Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis- A Never-ending Story

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to present a concise summary of the latest findings in the diagnostic workup of appendicitis. The reader is recommended to make decisions in a clinical setting by using his or her clinical expertise in the context of patient’s characteristics and best available evidence. Acute Appendicitis (AA) remains one of the most common diseases faced by the surgeon in practice. It is estimated that as much as 6% to 7% of the general population will develop appendicitis during their lifetime, and despite its high prevalence, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis can be challenging [1]. Acute appendicitis is the second most common diagnosis leading to malpractice claims against emergency physicians after acute myocardial infarction. No clinical presentation has been demonstrated to be predictive of appendicitis. The same may be said of laboratory evaluations, which are also weakly predictive when considered in isolation. Rather, it is the assessment of the collective body of information that allows more precise diagnosis [2]. Numerous biochemical parameters have been used to enhance and refine the clinical diagnosis of AA including [3] white blood cell (WBC) count, C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL6), Procalcitonin, hyperbilirubinaemia, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, Mean platelet volume (MPV) and platelet distribution width (PDW) , Serum Amyloid A ,Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), Urine Leucine-rich a-2-glycoprotein (LRG) and S100A8/ A9 (Cal-protectin).

CRP can be regarded as a predictor for complicated or late-stage appendicitis but it is not useful for early diagnosis. The evidence suggests acute appendicitis can be excluded when WBC, CRP and PMN ratio are all within normal limits. No diagnosis of appendicitis should be made based on increase of a single blood marker [4]. Studies confirm a relationship between IL-6 levels and the early phase of appendicitis, but it has not been demonstrated firmly to be better than other blood markers in the diagnosis of appendicitis [5]. Serum total/direct bilirubin estimation, which is a simple, cheap, and easily available test in every laboratory can be added to the routine evaluation list of suspected cases of acute appendicitis. Hyperbilirubinemia, especially with elevated direct bilirubin levels, may be viewed as an important marker for the prediction of appendiceal gangrene/perforation [6-8]. Procalcitonin (PCT) measurement cannot be recommended as a diagnostic test for patients with acute appendicitis and its routine use in such patients is not conclusive. The PCT values can be used as a prognostic marker and predictor of infectious complications following surgery for acute appendicitis and it can help to carry out timely surgical intervention, which is highly recommended in patients with values more than 0.5ng/ml [9].

Mean platelet volume (MPV) can change according to the stage of inflammation-associated diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, familial Mediterranean fever, and sepsis. MPV values in cases of appendicitis without perforation were lower than in cases of appendicitis with perforation. It is not considered a diagnostic test [10]. Serum Amyloid A (SAA) is a non-specific marker of inflammation which can be useful in the early diagnosis of appendicitis, but further studies are needed to prove this argument [11]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) acts on the bone marrow to stimulate production and release of granulocytes into the peripheral blood. It is associated with the severity of inflammation. It has the potential to aid other diagnostic measures while also signifying the severity of acute appendicitis [3]. Urine Leucine-rich a-2-glycoprotein (LRG) has been demonstrated to be helpful as a diagnostic marker for acute appendicitis in children. LRG has been found to be elevated in patients with acute appendicitis in the absence of macroscopic changes [12]. S100A8/ A9 (Cal-protectin), a calcium-binding protein, is correlated with acute inflammation specific of the gastrointestinal tract.

Calprotectin (Cal) is an antimicrobial protein and constitutes about 60% of cytosolic proteins in neutrophil granulocytes. It is secreted into the intestinal lumen during the early phases of intestinal mucosal damage. The transfer of inflammatory cells via the lumen of the vermiform appendix into the colonic lumen makes it possible to measure Cal in stool of patients with suspected appendicitis [13]. Fecal calprotectin could be helpful in screening patients with right lower quadrant pain suspected of acute appendicitis or infectious enteritis. Currently, fecal calprotectin has been identified as a valuable diagnostic marker for a series of bowel pathologies, e.g. chronic inflammatory bowel diseases [14]. An intuitive approach to diagnosis of appendicitis is to recruit a biomarker panel, the APPY1™ test, which consist of the combined values of total white blood cell count (WBC), plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) level and plasma myeloid related protein 8/14 (MRP 8/14 or calprotectin) level in a proprietary mathematical algorithm expressed as 0.1177(WBC k/ μl) + 0.0202(CRP μg/ml) + 1.6(MRP 8/14 μg/ml) +2.4372 = A, with A being a single numerical value [15].

The results suggest that adult patients with abdominal pain for whom acute appendicitis is the primary diagnosis might have imaging postponed in favor of clinical observation in the setting of low risk results on the APPY1 test or with negative results for both WBC and CRP. A variety of radiographic studies may be used to diagnose appendicitis. These consist of plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scanning, ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT scanning is the most common imaging study to diagnose appendicitis and is highly effective and accurate. The recommended imaging protocol from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Surgical Infection Society includes the intravenous administration of contrast material only. Oral and rectal administration of contrast material is not recommended [16,17].

CT is not recommend in cases in which appendicitis is strongly suspected on clinical grounds due to disadvantages including radiation exposure, risk of contrast induced nephropathy, and cost. Additionally, the time required for performance of CT, particularly when oral contrast is needed, may add substantially to ED length of stay, a contributing factor to ED crowding. Abdominal US is the preferred imaging modality to evaluate children with suspected appendicitis because it has good diagnostic performance, lacks ionizing radiation and does not require intravenous contrast agents [18]. Various scoring systems including the Alvarado, Samuel, Tzanakis, Ohmann, Eskelinen, Fanyo, Lindberg and Logistic score of Kharbanda have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of AA in order to decrease negative appendectomy rates. The Alvarado score, derived from retrospectively collected data from 305 adult patients in the mid-1980s, is the best-known clinical prediction rule for estimating the risk of appendicitis. The Alvarado scoring system most accurately predicts appendicitis in men and can be used as a reasonable starting point in the assessment of suspected appendicitis cases [19].

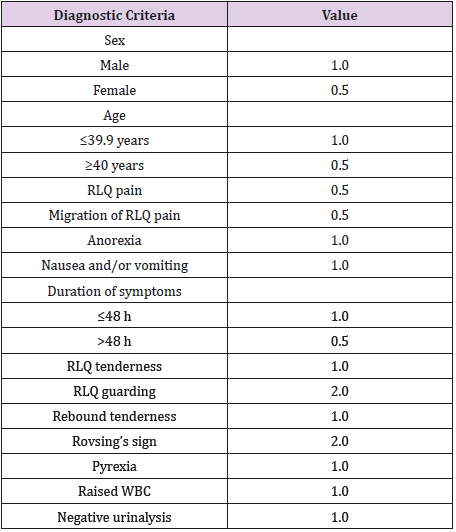

A new score, namely MESH (Migration, Elevated WBC, shift to left, and Heel drop test) score has been introduced recently to further facilitate the diagnosis of appendicitis. Heel drop test is conducted as follows: patients are asked to look at the face of the physician running the test and come down with all his/her weight on his/her heels after standing on his/her toes on a smooth surface. During this exercise, findings indicative of perceived pain is evaluated as a positive result in the heel drop test [20]. While the heel drop test was originally introduced to evoke peritoneal irritation by moving intraperitoneal contents up and down and to detect the presence or absence of peritonitis, especially in acute appendicitis, it is also considered the most sensitive test for meningitis [21]. Another score, The Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha appendicitis (RIPASA) score was developed in 2010 in Brunei (Table 1) and tested and replicated in Asian and Middle Eastern populations in Pakistan, China, India, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. It is comprised of 15 demographics, clinical and laboratorybased parameters and has a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 81% for AA in Eastern populations at a cut-off score of 7.5. The RIPASA score is a simple, non-invasive and rapid scoring system [22]. Diagnosis of appendicitis remains a never-ending story and a valid, reliable, sensitive, specific, minimally invasive, and low-cost test is eagerly awaited.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.