Anatomization of Mortality Trends in Under-Twelves in a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Nigerian: A Cross Sectional Evaluation

Introduction

Background of the Study

The WHO Convention on the rights of the child defines a child as “a person below the age of 18 years unless the laws of a particular country set the legal age for adulthood younger” [1]. Under-12 mortality is the probability of a newborn baby dying between birth and exactly 12 years of age. Child mortality, also known as child death, refers to the death of children under the age of 14 and encompasses neonatal mortality, under-5 mortality, and mortality of children aged 5-14. There is paucity of information about the direct causes of child mortality in developing countries. Child survival remains an urgent concern and as such should not be treated with triviality. Child mortality is a sensitive indicator of a country’s development and a representation of its priorities and values [2-5]. It is unacceptable that about 16,000 children still die every single day – equivalent to 11 deaths occurring every minute. This increasing death toll has a significant effect on the economy of a nation as potential human resources are lost at such tender ages. Socioeconomic determinants, environmental determinants, nutritional status, personal illness control and growth faltering are some of the risk factors known to have a strong relation to child mortality.

Children who die within the first 28 days of life often do so as a result of diseases and conditions that are readily preventable or treatable with proven, cost-effective interventions. Globally, 3 in 4 neonatal deaths are caused by preterm birth complications, complications during labor and delivery (intrapartum-related complications), and sepsis [6,7]. It becomes critically important to accelerate progress in saving the lives of newborns with simple, cost-effective interventions as well as quality care before, during and immediately after birth. This necessitates an evaluation of mortality trend in this population to identify and analyze the risk factors of death as timely and accurate information on the causes of deaths in children less than 5 years old helps in guiding the efforts made to improve child health as a proactive and preventive tool for intervention [8,9]. Data on morbidity and mortality are essential for assessing population health status and disease burden. Valid information on causes of death is an essential tool for the development of national and international health policies for prevention, better management, and control of diseases and complication [10,11]. Most mortality information of countries, communities and facilities are readily available in demographic and health surveys, censuses, hospital medical records among others [12]. Retrospective reviews of these data sources have been the trend of most studies [3,13,14]. This study provided information on the mortality trends in under-12 and explored the associated factors.

Methods

Study Area

The study area was Anambra State, an inland state located in the south-central area of southeastern Nigeria. Its capital is Awka. Anambra state boasts of an undulating landscape with tall trees and vegetation and also mineral resources. It is bordered to the north by Kogi State, to the south by Imo State and Rivers State, to the east by Enugu State and to the west by Delta State. Together with Imo State, it forms the heartland of Igbo land. Nnewi is the second largest city in Anambra State located east of the Niger River and about 22 kilometers southeast of Onitsha. It is comprised of Nnewi North commonly referred to as Nnewi Central; where the tertiary health care facility is located; and Nnewi south.

Study Design

The study was a cross-sectional retrospective study which utilized records and documentation of the death register and post-mortem reports. Documentations used covered four year period which spanned from January 2014 to December 2017 predominantly from the pediatric department not excluding other departments of the hospital where the population group under study were managed. A detailed collection of data was done and systematically categorized into age, sex, clinic, definitive diagnosis, risk factors, the frequency of each factor, yearly occurrence. This provided an insight into the leading cause of mortality in pediatrics managed in various clinics of the hospital.

Participants

Dead under-12 aged children’s medical records from the death register, mortality record and medical records.

Variables

Age, sex, diagnosis/risk factors, unit,

Study Setting

The study was conducted in a tertiary health care facility in Anambra State, South East Nigeria having most specialties in medicine. The facility is The Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH), Nnewi, providing health care services to the teeming population of Anambra State and environs.

Study/Sample size: All the eligible data which met the inclusion criteria were collected from the register. A total of 1004 eligible data was obtained and all were used and properly analyzed to increase reliability.

Bias

Every form of identification was excluded from the data

Ethical Consideration: Before commencement of the above study, ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Research and Ethics committee of the tertiary health care facility.

Inclusion Criteria:

a. All registered medical records of under-twelve death cases from January 2014 to December 2017.

b. All hospitalized and outpatient registered death cases for this population.

Exclusion Criteria:

a. All registered under-twelve death outside the period from January 2014 to December 2017.

b. All none- registered death cases pertaining to the population under study

c. All death cases of children beyond twelve years of age.

Data Collection

Data on mortality of under-12 children was collected using the patient’s medical records and death register at the records section of the Pediatric Department. A detailed data collection was done using structured data collection form and categorized according to the various age distribution, gender distribution, clinics and the health condition implicated in each death case from the period of January 2014 to December 2017. The data was and entered into the data collection forms in a presentable manner. This provided an insight into the leading risk factor of mortality and its frequency between the periods.

Data Management

All data was collated and entered into Microsoft Excel, 2010 spread sheet and cleansed. Thereafter, data was summarized with descriptive statistics. Level of association between death prevalence and various parameters (clinic, age and sex and year) was carried out using Chi-square test.

Results

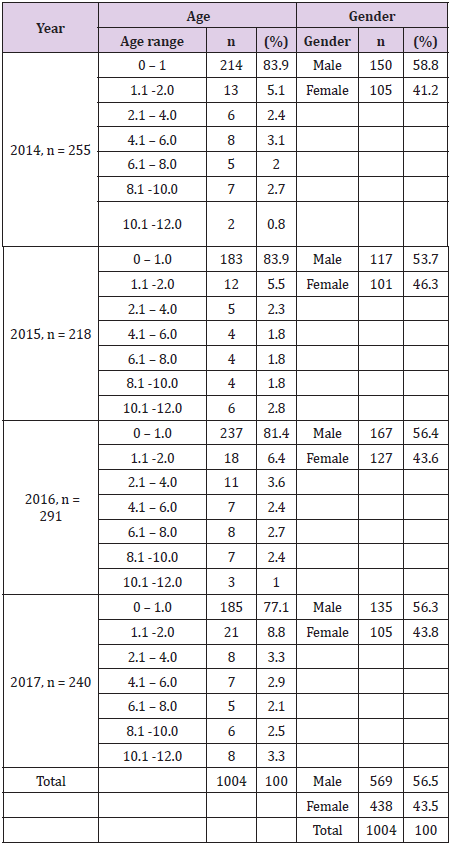

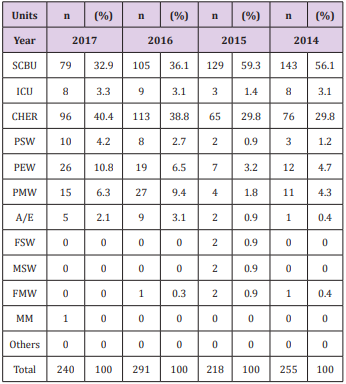

Test of association using Chi-square showed no statistically significant association (P>0.05: p =0.999, χ2 = 5.908) between age distribution of death record among the four years. Table 1 shows the distribution of children mortality with respect to gender. There was a higher death rate among male children than female children in four years. Generally, out of 1004 mortality record, the majority (569.0, 56.5%) were males than females (438.0, 43.5%). Chisquare test revealed a statistically significant association (P<0.05: p =0.0005, χ2 = 65.004) between the number of the death record for males and females in 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017. Similar mortality trend was observed among the 11 clinics from 2014 to 2017 in Tables 2 & 3. Descriptive statistics revealed that Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU) and CHER (Children Emergency Room) were the two major clinics with highest death records.

Table 1: Distribution of death among children of 12 years and below in Nnamdi Azikiwe Teaching Hospital.

Where the n= total number of deaths in a year.

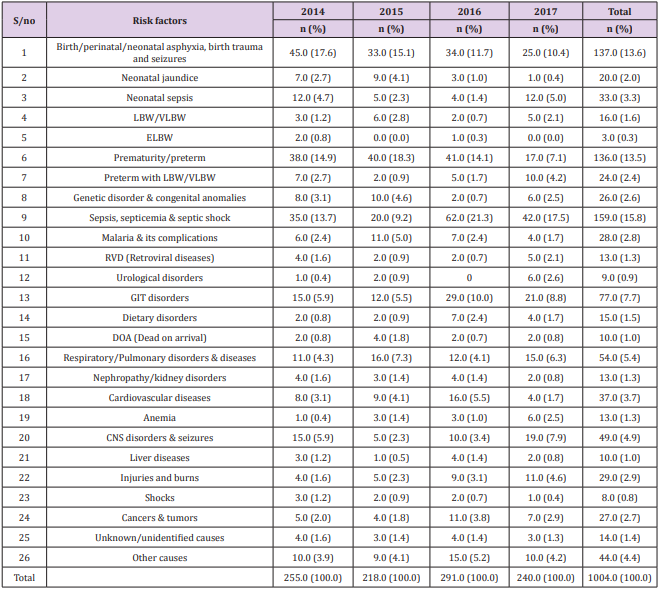

Table 3: Risk factors responsible for death among children in four years in Nnamdi Azikiwe Teaching Hospital.

These were followed by PSW (Pediatric Surgical Ward), PEW (Pediatric Extension Ward), PMW (Pediatric Medical Ward) and Accident and Emergency (A/E). Other clinics had little or no death records. Chi-square test revealed that death record among the 11 clinics was statistically significantly associated with years (P<0.05: p =0.039, χ2 = 41.270). In other words, the level of death distribution in the 11 clinics in four years varied significantly. Chisquare test revealed that the distribution of death record among the four years were not statistically significant (P>0.05: p =0.891, χ2 = 60.347). Test statistics results revealed a high infant mortality rate which included perinatal and neonatal mortality with the highest mortality among children born between 0-1 years as compared to other age categories. However, there was no significant level of association between age distribution of death record among the four years with a P-value greater than 0.05, (p=0.999).

Discussion

Sex and gender differentials in survival result from a complex interplay of biological and behavioral factors that impact mortality at different stages in the life course. In countries with very low mortality, females have lower mortality than males at all ages. In the four years, the majority of the deaths recorded from the study were among the male children (569.0, 56.5%) as compared to the female children (438.0, 43.5%). Hence, more than half of the deaths recorded were found among the male gender. Also, there was an observed significance level of association between the number of the death record for males and females in the respective years. This is shown by a P-value of p=0.0005 (P< 0.05). The children were managed in various clinics of the hospitals ranging from special care baby unit (SCBU), children emergency room (CHER), pediatric medical ward (PMW), pediatric surgical ward (PSW), A/E (Accident and Emergency), intensive care unit (ICU), and pediatric extension ward (PEW). Of all the 11 clinics where these children were managed, SCBU and CHER had the highest death records. The level of death distribution in the various clinics in four years varied significantly.

Most under-five deaths and in general child mortality, are caused by diseases that are readily preventable or treatable with proven, cost-effective interventions. Infectious diseases and neonatal complications are responsible for the vast majority of under-five deaths globally. The probability of deaths among children aged 5-14 was 7.5 (7.2, 8.3) deaths per 1,000 children aged 5 in 2016 substantially lower than among younger children. Still, 1 (0.9,1.1) million children aged 5-14 died in 2016. This is equivalent to 3,000 children in this age group dying every day. Among children aged 5-14, communicable diseases are a less prominent cause of death than among younger children, while other causes including injuries and non-communicable diseases become important. Among children aged 5-9 years and younger adolescents aged 10- 14 years, communicable diseases are a less prominent cause of death than among younger children, while other causes become important. For instance, injuries account for more than a quarter of the deaths among this age group, non-communicable diseases for about another quarter and infectious diseases and other communicable diseases, perinatal and nutritional causes for about half of the deaths. Drowning and road injuries alone account for10 percent of all deaths in this age group [15].

Despite the substantial progress in reducing child deaths, children from poorer areas or households remain disproportionately vulnerable. It is critical to address these inequities to further accelerate the pace of progress to fulfill the promise to children. This goes to implicate poverty as an important risk factor to child mortality. The risk implicated in under-12 mortality from the study included: birth/perinatal/neonatal asphyxia and birth trauma and seizures, neonatal jaundice, neonatal sepsis, intrapartum complications, prematurity, low birth weight (LBW), sepsis, malaria, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory/pulmonary disorders, cardiovascular diseases, liver diseases, retroviral diseases, congenital anomalies, etc. Gastrointestinal disorders implicated include intestinal obstruction, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastroenteritis, enterocolitis, Respiratory/pulmonary disorders implicated included: pneumonitis, bronchopneumonia, tracheoesophageal fistula, pulmonary tuberculosis among others. Gastroschisis, trisomy’ 21, down syndrome etc. constitute genetic disorders. Also, dietary disorders such as protein-energy malnutrition, kwashiorkor, marasmus, etc. were also risk factors that predisposed these populations to death.

Of all these causes, extreme low birth weight (ELBW) had the lowest risk of death. There was no significant level of association between the number of death records and the various risk factors to mortality evidenced by a P-value of 0.891. Maternal health is as important as child health as it has a direct impact on child health and mortality. The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) identifies that children are at a greater risk of dying before age five if they are born in rural areas, among the poor, or to a mother deprived of basic education. The World Health Organization recognizes reproductive health as inclusive of “the right of access to appropriate health-care services that will enable women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant [16,17]. Maternal factors such as maternal education, a birth interval greater than 24 months, adequate breastfeeding are significant protective factors for child survival. Maternal education plays a vital role in the utilization of antenatal care [18-23]. In line with the general perception and a well-documented fact, the effects of breastfeeding and birth interval of more than 2 years are significant protective factors [24-27].

Infants not exclusively breastfed are 15 times more likely to die from pneumonia and 11 times more likely to die from diarrhea than those who are exclusively breastfed [28]. The UNICEF report projects that if all birth to pregnancy intervals were 3 years, approximately 1.6 million under-five deaths could be prevented annually [29]. Efforts should continue to delay the next pregnancy. In addition, maternal age, i.e., the age of the mother at their first birth is a key correlate of child health outcomes. Teen mothers have children with the worst health outcomes and children of mothers who have their first birth in their early 20s are also at risk of poor health outcomes compared to first-time mothers in their late 20s. Raj et al showed that children born to mothers in India who were married below the age of 18 were at a higher risk of stunting and underweight as compared to children of women who had married at 18 or older. The effect of the young age of the mother at first birth on poor child health outcomes reflects the interplay of biological and social factors [30-35]. Other factors which come to play include proper sanitation and hygiene, nutrition, etc. Poor sanitation and hygiene contribute to fecal pathogens in the environment which, when ingested through contaminated food and water lead to disease.

Under-nutrition has a direct effect on child mortality as it compromises the immune function and increases susceptibility to infectious disease. It is an underlying cause of more than 3 million child deaths per year and is also a consequence of poor health, as infectious diseases increase energy requirements and often reduce appetite and nutrient absorption [36-38]. Optimal maternal nutrition is an important contributory factor to the survival of both the mother and child and promotes women’s overall health, productivity, and well-being. Two critical pathways through which women’s nutrition affects survival outcomes include anemia and calcium deficiency. Pregnancy increases the risk of maternal anemia as the maternal iron requirements increase to support maternal and fetal needs. Epidemiological studies have linked low calcium intake to gestational hypertension which could lead to preeclampsia and eclampsia, now the second most important cause of maternal mortality worldwide [39]. The impact of institutional or nosocomial and community-acquired infections cannot be undermined [40-42].

Conclusion

In line with similar studies, there exists a trend of mortality in children with respect to age and gender. These mortality cases are attributable to various factors which have been identified as well as some unknown or unidentified causes (which could be a lag in proper documentation). Mortality can thus be said to arise from the interplay of various factors, hence, hospital-based records to a considerable extent provide relevant information on the trends as well as factors implicated in the mortality trends. This emphasizes the importance of maternal and child health in an economy.

Limitations of the study: Incomplete documentation by the health facility as some diagnosis that leads to death was not stated hence making it difficult to identify the cause of death in such children. The possibility of incomplete documentation and retrieval of data from the primary data sources cannot be completely ruled out.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.