Asymptomatic Submucosal Lipoma of the Anal Canal: A Report of an Incidental Colonoscopic Finding in an Elderly Patient with Colonic Diverticuli

Background

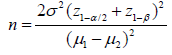

Lipomas are benign adipose tissue tumors commoner between

the ages 40 -60 years and have a preponderance in the male gender

[1]. They may be solitary or multiple, superficial or deep in location

and are usually asymptomatic. Cosmetic concerns (in larger

lipomas), pain or discomfort are the common indications for removal

of superficial lipomas and these commonly occur in the trunk, head

and neck regions. Deep-seated lipomas are relatively uncommon;

they occur in the thorax, retroperitoneum or abdominal cavity [2].

Intra-abdominal lipomas usually affect the omentum, mesentery,

the submucosa and subserosa of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [3].

Lipomas are the second most common non-epithelial benign GIT

tumours after leiomyomas [4]. The most commonly affected region

of the GIT is the colon, with the highest incidence at the cecum,

ascending colon, transverse colon, and the left colon (in decreasing

order as one approaches the rectum) [4]. Occurrence of a lipoma in

the anal canal is extremely rare with only one case reported so far

by Porta et al in 1979! [5].

In diverticulosis of the colon, there is a transmural outpouching of the colonic mucosa through an area of weakness. This mural weakness-the primary pathology in diverticulosis-is of multifactorial aetiology and the predisposing factors include weakened points of vascular entry into the colonic wall, reduced dietary fiber, hereditary factor, reduced physical activity and obesity [6]. In ventral abdominal wall hernias, stretching of abdominal musculature (because of an increase in its content as seen in obesity) and separation of muscle fibers with weakening of aponeurosis are known to weaken the integrity of the fascia leading to herniation [7]. Whilst the role of mural adipose tissue in the development of GIT diverticula is yet to be established, Yekeler et al have however reported a case of two coexisting rarities- an oesophageal lipoma that resulted in an oesophageal diverticulum due to extramucosal impact of the lipoma [8]. We present an interesting incidental finding of a submucosal anal lipoma in an elderly man who had a concomitant presence of colonic diverticula with an increased submucosal adipose tissue in the vicinity of the diverticuli. This case is reported in line with the SCARE criteria for case reports [9].

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old male retiree was referred for colonoscopy

on account of recurrent passage of bloody stool of three months

duration, last episode being two weeks earlier. He had no history

of anal pain, discomfort, or anal protrusion. There was no change

in bowel habit, reduction in stool caliber, melaena, abdominal pain

or tenesmus. There was no history of anorexia, haematemesis,

early satiety and he does not have a history of peptic ulcer disease.

He had no fever, weight loss or any comorbid illness. He had no

history of anal trauma or previous anal surgery. No personal or

family history of similar illness or malignancy in the past. He was

not on any anticoagulation. On examination, he was pale, otherwise

other aspects of his general and systemic examinations were

normal with a body mass index of 23.1 kg/m2. A pre-procedural

rectal examination did not reveal any abnormality. Colonoscopy

revealed multiple diverticuli in the caecum, ascending colon and

descending colon (Figure 1a) with a 5mm x 3mm sessile polyp in

the descending colon.

There was a yellowish, oval, submucosal sessile mass (about

10mm x 8mm in widest diameters) with a lobulated surface, about

3cm from the anal verge (Figure 1b). The mass exhibited positive

pillow or cushion sign. The mucosa of the transverse colon, sigmoid

colon (Figure 1c) and rectum was normal. However, there was an

increased yellowish hue to the large bowel submucosa around the

anal canal (Figure 1d) and the sites of diverticula (Figure 1e). No

stigmata of recent bleeding were seen. The descending colonic

polyp was removed with cold biopsy forceps (Figure 2a). The anal

submucosal mass was biopsied revealing the characteristic naked

fat sign (Figure 2b). The anal submucosal mass was reported to

be benign at histology while the descending colonic polyp was

reported as an adenomatous polyp with low grade dysplasia. He

has been on conservative care for the colonic diverticulum and has

remained asymptomatic both for the diverticulum and the anal

submucosal lipoma 3 months post colonoscopy.

Discussion

Lipomas are common benign tumour of mature adipose tissue

that usually occur in superficial locations – most common location

being subcutaneous. The relatively uncommon deep-seated

lipomas either present atypically or as incidental findings [10]. In

the GIT, they are usually subserosal or submucosal in location, the

colon being the most affected region. Involvement of the rest of

the large bowel decreases anal-ward. We presented an extremely

rare report of a submucosal lipoma of the anal canal with a curious

finding of concomitant existence of divertculi at areas of increased

submucosal adipose tissue. We discuss this case in terms of rarity

and then, its peculiarities. The rarity of this case lies in the fact that

it is a deep-seated lipoma occurring in the anal canal. The most

distal GIT lipomas reported in the literature are those of the rectum

and these presented as polypoid submucosal masses protruding

through the anal canal or casuing rectal bleeding [11,12]. Beyond

the rectoanal canal, the perianal region, lipomas are also rare with

a report of a perianal lipoma occurring years after surgery for a

perianal abdscess [13].

The aetiology of the perianal lipoma was likely traumatic,

similar to the report by Uscilowska et al on para-anal lipoma

resulting from perineal trauma [14]. Beyond trauma, the other risk factors for lipoma formation include genetic predisposition,

obesity, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus [15]. There risk

factor for lipoma in our patient was not apparent. This was not a

surprise since such deep-seated lipomas are incidentalomas like

in our patient. Colonic lipomas are usually asymptomatic except

when they are larger than 2cm, torsed, or pendulated. The small

size, submucosal location and sessile nature of the lipoma in our

patient may explain the asymptomatic nature. The sigmoid colon

is said to be the commonest site of colonic diverticulosis, although

a study on our patient population by Akere et al revealed right

colonic preponderance [16,17] The endoscopic appearance of

most colonic diverticuli is that of an outpouching of the mucosa

with an otherwise pink-looking mucosa/submucosa due to the

rich vasculature of these layers. In diverticulitis, the mucosa of the

diverticulum is reddened with or without a surrounding fibrinous

slough [18].

The peculiarity of our report is the increased submucoal

adiposis in the vicinity of colonic diverticuli, with a predominantly

yellowish (than pink) hue to the mucosal color (Figure 1e). These

diverticuli involved the caecum, ascending and descending colon

with none in the sigmoid colon, the mucosa of which appeared

normal (Figure 1c). It therefore stimulates curiosity as to a possible

link between increased large bowel mural adiposi and a possible

predisposition to subsequent diverticulum formation in the areas

where these adipose tissues are located. The plausibility of this

link may not be far-fetched if the underlying pathology of colonic

diverticulum- mural weakness-is considered. It is therefore more

compelling to associate increased submucosal adiposis in our

patient with his colonic diverticuli considering the established

effect of same adipose tissues on tougher tissues like aponeurosis in

abdominal wall hernias. Whilst colonic diverticulosis is commoner

in older patients like our patient, Brouland et al reported a large

colonic diverticulum in a young male arising due to colonic mural

weakness by multiple colonic lipomatosis [19].

The risk factors for colonic diverticulosis include comorbidities

(like hypertension and diabetes mellitus), increased luminal

pressure (from colonic dysmotility, reduced dietary fiber), genetic

risk factors (like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Coffin-Lowry and renal

polycystic disease), obesity/reduced physical activity, smoking

and increasing age [20]. Age alone may not explain the diverticuli

seen in our report and none of the other known risk factors was

apparent. Although the endoscopic features of the submucosal

anal mass we reported were in keeping with a lipoma, histological

report did not show the presence of adipocytes. This is a common

limitation of endoscopic biopsies where only the mucosal layer is

usually biopsied except multiple biopsies are taken at the same

spot to include deeper layers. A limitation of this report is our

inability to do endoscopic ultrasound which would have confirmed

the location of the lipoma. Facility for endoscopic ultrasound is not

available in Nigeria as at the time of this report to the best of our

understanding.

Conclusion

Lipomas of the anal canal are rare. Although an incidental

endoscopic finding in this report, coexistence of large bowel

lipomas with increased submucosal adiposis in the vicinity of

colonic diverticuli may suggest an aetiological role of such lipomas

in colonic diverticulosis.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.