Tracheal Stenosis as a Consequence of Orotracheal Intubations and Mechanical Ventilation in Time of Pandemic

Introduction

Currently one of the public health problems worldwide is COVID 19, this is a pandemic infectious disease caused by a coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV- 2) [1]. Symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, nausea and gastrointestinal symptoms are the majority of symptoms present in patients with COVID 19, but a certain small group of these patients may choose to present serious complications such as interstitial pneumonia, acute insufficiency, and distress syndrome. Respiratory disease (ARDS), multiple organ failure and even death [2]. 5-12% of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 require admission to the intensive care unit; which often require the use of prolonged mechanical ventilation with high positive pressure at the end of expiration (PEEP) through an endotracheal tube [3]. Tracheal intubation is a procedure that is of great importance, but it can cause damage to the mucosa and necrosis in the tracheal wall, which would lead to laryngotracheal stenosis [4] this is the abnormal decrease in the caliber of the trachea due to scar retraction. or deposit of pathological tissue; tracheal stenosis is one of the main causes of chronic upper airway obstruction. Therefore, it is important to carefully monitor those patients with COVID-19 who, during their stay in the ICU, had the use of mechanical ventilation as a requirement.

Methodology

A bibliographic search of information published since 2015 was carried out in the databases of Scielo, PubMED, Academic Google, Elsevier, Medline. The search was carried out with articles in Spanish and English and the use of keywords such as: Tracheal stenosis, COVID-19, postintubation.

Results

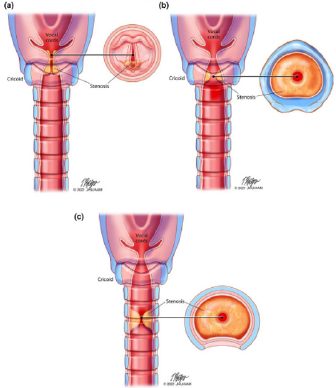

In a small fraction of patients with COVID-19 they require mechanical ventilation, so a long exposure is the cause of tracheal stenosis. Tracheal stenosis has been characterized as one of the most common complications in relation to acute injuries of the airways that involves a partial or complete narrowing of the lumen in the airways at the level of the larynx, subglottic space or the trachea, but the most common site of tracheal stenosis is the subglottic space, this being the narrowest part of the adult airway. Depending on the length, location, and extent of the obstruction, the severity of the tracheal stenosis that occurs will determine (Figure 1). Post-intubation tracheal stenosis can present as a simple stenosis in which the circumferential network measures less than 1% and complex stenosis of irregular shape that measures more than 1cm, presenting in patients an acute direct trauma at the time of intubation. Tracheal stenosis appears 1 to 6 weeks after extubation. Respiratory stridor manifests 25-30% narrowing of the tracheal diameter, while dyspnea occurs in 50% [5]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of mechanical ventilation has been increasing due to the trauma presented in the decrease in visibility when prolonged intubation occurs in which in patients with COVID-19 it has a mean duration of 17 days [6]. When a person presents endotracheal stenosis, they are usually initially asymptomatic or only have mild symptoms for months or weeks, but as time progresses. The most common symptom is respiratory stridor, however some patients present dyspnea, dry cough, dysphagia as well as wheezing or a history of recurrent bronchitis [7]. Post-intubation tracheal stenosis is a well-known risk in prolonged endotracheal intubation. Gervasio et al. (2020) report the case of two patients with endotracheal stenosis. The 54-yearold man was admitted for COVID-19 10 days after a tracheostomy was performed, the patient was taken to the emergency room with respiratory distress, which showed signs of tracheal stenosis when the tomography and bronchoscopy were performed. The other patient, a 43-year-old man, presented severe respiratory distress, which at 18 days was taken to the emergency room with severe difficulty presenting visible signs of tracheal stenosis, so that in bronchoscopies, markedly fibrotic inflamed granulation tissue could be seen in the trachea [8].

Discussion

During the Covid 19 pandemic, respiratory complications present during the course of the disease were the main cause of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), so the occupancy rates of beds and intubation equipment increased to very high levels, since due to the respiratory urgency that the patients presented, intubation and mechanical ventilation was positioned as the main management tool for medical and intensivist personnel. This surgical procedure, despite being the most appropriate management option for the treatment of respiratory complications, in turn represents a risk of viral infection, because, when a tube is entered through the trachea, it is exposed to a series of viruses that can create a focus in this area, unleashing an inflammatory response, which conditions the state of intubation to long periods of time and the development of other underlying complications such as tracheal or subglottic stenosis. In their case report, Scholfield et al. Present 3 cases of tracheal stenosis after orotracheal intubation in patients who had undergone it, who developed various infectious and gastric complications; and in whom a tracheostomy was necessary, so they concluded that prolonged intubation, increased time to tracheostomy, high cuff pressures, and large endotracheal tubes put Covid-19 patients at higher risk subglottic stenosis. The risk is increased by the inflammation of the upper respiratory tract caused by the virus and the comorbidities associated with Covid-19 [9].

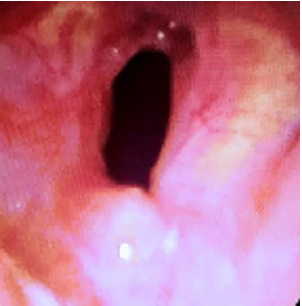

Regarding risk factors, obesity, advanced age and pathologies after covid 19, increase the possibility of the need for intubation and therefore a tracheostomy as an alternative to the development of this condition, however, this is a surgical procedure that also represents a risk of infection, for which Mattioli et al., in their letter to the editor, propose and recommend the implementation of a balloon dilation procedure with eventual intralesional injection of corticosteroids, even in the case of circumferential and complex stenosis (Figure 2) [10]. Because the development of this stenosis is an obvious response to intubation, there are no actions that prevent it altogether, complemented by what was concluded by Fiorelli and others, in their letter to the editor, where they likewise acknowledge that tracheal surgery it should be reserved for high-complex stenosis or tracheal stenosis in the form of a net previously treated by endoscopic “bridging” treatment that can no longer be treated with interventional procedures [11]. During the intubation process with a video endoscope, which is inserted in order to better observe the state of the larynx and trachea. Such procedure is exposed by Tsunoda and others, who in their report expose the situation of various patients, that when developing tracheal stenosis the patient increases their levels of asphyxia, for which various surgical processes are performed such as tracheostomy that in addition to having systemic effects It can also cause infection from cough, sputum, or even blood. And when observing through a video endoscope, they found that the primary disease that developed airway stenosis was acute epiglottitis due to pharyngeal and deep neck abscesses in three cases. The last case was laryngeal edema due to Ludwig’s angina. All patients underwent uneventful intubation and dyspnea ceased immediately. Three cases accompanied by a deep throat and pharyngeal abscess required surgical drainage. These cases underwent tracheostomy, so the tube was extubated [12].

It is imperative to take into account that not all patients present this complication, as Moreira and others assure in their comparative study between patients with and without tracheal complications, where it was found that all had demographic characteristics, comorbidities, parameters and duration of ventilation and similar therapeutic management, and ten (71%) patients with tracheal damage had tracheal stenosis, 6 (43%) pneumothorax, and 13 (93%) had pneumomediastinum, while these complications were not seen in COVID-19 patients without tracheal damage [13]. Therefore, as Espinoza affirms, laryngotracheal stenoses due to procedures such as prolonged intubation or post-tracheostomy in patients undergoing IMV represent a challenge in their treatment, even more so in the pandemic in which we find ourselves, since patients infected with COVID-19 they have a persistent inflammatory process that produces abnormal tissue repair [14]. From the personal point of view of the patient who must undergo intubation, this procedure is usually impressive, stressful and worrisome for him, since seeing himself in such a situation due to his complication is overwhelming, so depending on the setting psychic, this is only the reflection of the last attempt of the conscious subject to preserve life, regardless of the prognosis and its consequences [15].

In their case report, Giordano et al. Report on a 64-year-old patient who was admitted to the emergency department with exertional dyspnea, six months earlier, had undergone mechanical ventilation through an orotracheal tube for the first week and then through a tracheostomy tube for the next 35 days for severe COVID-19 pneumonia. A high-resolution coronal computed tomography of the thorax was performed, which showed, when passing through the tracheal lumen, a severe stenosis of the lumen of the cervical portion of the trachea [16], which confirms that in most cases of intubated patients present this dyspnea and asphyxia due to the developed stenosis. Due to this, it is necessary to implement various alternatives to improve the patient’s condition, such as position, also associated with the presentation of sequelae generated by immobility and prolonged rest [17] but which was formally described in a protocol in Jiangsu (China), where the rate of invasive mechanical ventilation remained below 1% with the implementation of various therapeutic measures including pronation in this group of patients [18], which classifies this alternative as effective. There are certain factors that can contribute to increasing the risk of post-intubation stenosis, such as: traumatic or prolonged intubation, multiple extubations and subsequent reintubations, excessively large tube, movements of the tube or of the intubated patient and local infection [19], therefore, the most widely used measure continues to be the open technique tracheostomy and adequate post-tracheostomy care [20], in addition to preventive infection measures.

Conclusion

Tracheal stenosis is a direct consequence of orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, which in the long term is the main reason for admission of patients to the emergency services, who share similar risk factors and also the respiratory complication due to covid 19. Through the Intubation procedure, when a foreign body enters the trachea, and together with the possible bacteria present by cough, sputum and blood, the chances of creating a focus of infection in the area increases, which in turn increases the intubation period and therefore the involvement of the trachea, which must later be corrected with a tracheostomy, which tends to be an invasive procedure, for which it is necessary to implement a series of preventive measures for both intubation and change of the position of the patient, and the reduction of longterm complications produced by stenosis, however, this is still the subject of study in l to present.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.