Pregnancy Induced Hypertension in Kabo Local Government Area of Kano State, Nigeria

Introduction

Despite the high technological inclination in the 21st century,

especially in the area of health, the rates of maternal mortalities and

morbidities are still very high in women worldwide. The occurrence

of maternal hypertensive disorders is found to have about 20.7

million women in 2013 and about 10% of pregnancies globally

are complicated resulting from pregnancy induced hypertension

Sharma, et al. [1]. In the United States, hypertensive disease of

pregnancy affects about 8% to 13% of pregnancies Mohan, et al. [2].

Annually, an estimated 2.9 million babies die during the neonatal

period and 2.6 million babies are stillborn around the world due to

PIH. According to WHO (2018), the rate of stillbirth is 21.9 per 1000

births in women with a pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) and normotensive women 8.4 per 1000 live births in china Xiong T, et

al. [3]. Pregnancy Induced Hypertensions (PIHs) are responsible

for 70,000 maternal deaths universally, killing one woman every 11

minutes Magee, et al. [4]. It is the second leading cause of maternal

mortality in Bangladesh, according to the Bangladesh Maternal

Mortality Survey (2017), about 24 percent of the country’s maternal

deaths are caused by pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (PE/E) NIPORT, et

al. [5], which affects women during pregnancy, childbirth, as well as

postpartum. Factors, such as lack of health care provider capacities

to detect, prevent, and manage PE/E, late referrals of HIP clients,

late attendance and lack of antenatal care (ANC) and awareness

about PE/E among communities have been associated as reasons

for most of these preventable deaths Warren, et al. [6].

Deruelle, et al. [7] reported that about 25 percent of women

with PIH, especially those with a dangerous condition, experience a

decline of end-organ functions during puerperium (the 6 to 8 weeks

after delivery, during which pregnancy changes return to baseline).

PE early in pregnancy (less 34 weeks of gestation), presenting in

a severe form, or persistence of proteinuria more than three to

six months after delivery suggests possible chronic hypertension

or renal disease. Women with pre-eclampsia are also at increased

risk for venous thromboembolism in the postnatal period (after

delivery), and those women should receive thromboembolic

prophylaxis after delivery until they are fully recovered, usually

within four to six weeks RCOG [8]. Similarly, women with preterm

pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension have been found

to develop persistent cardiovascular impairment one year after

delivery Melchiorre, et al. [9], including other chronic diseases such

as chronic hypertension, stroke, renal disease, diabetes mellitus,

and ischemic heart disease. Infants born to women with PIH also

require special attention in the immediate postnatal period due to

a combination of short and long term risks. Standard international

guidelines recommend lifelong care and monitoring, or a minimum

of care and monitoring for six months to one year after delivery.

Studies propose that complications associated with PIH continue in

the immediate postnatal period and longer NICE [10].

One of the goals of the United Nations Sustainable Development

Goal (SDG) is to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less

than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 United Nations [11]. The

SDGs aim to uphold the momentum of the Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs), which in its relentless effort catalyzed a global

reduction in maternal deaths from approximately 390,000 in 1990

to 275,000 in 2015 Graham, et al. [12] United Nations, 2018). The

strains of maternal mortality remain unduly borne by women in

less-developed countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (66%,

201,000 deaths) and southern Asia (22%, 66,000 deaths). One of

the leading causes of maternal death (and disability) worldwide is

pregnancy induced hypertension Payne, et al. [13]. The statistical

figures of this problem in less developed countries have varied from

4.0% to 12.3% (Sebastia et al., 2015; Berhe et al., 2018). Pregnancy

induced hypertension is also one of the major leading causes of

pregnancy associated with morbidity and it is the most recurrent

cited cause of maternal death Ethiopian Journal of Health Science

[14]. Despite the fact that hypertensive conditions in pregnancy

is leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality during

pregnancy, little is known about its magnitude among pregnant

women in Kano and, specifically in Kabo Local Government Area.

This study therefore aims to fill this gap by considering pregnancyinduced

hypertension, the signs, associated risk factors and

prevention and management among pregnant woman attending

antenatal service in Kabo.

Basic Tools of Scientific Inquiry

The study was guided by the following research questions:

1. What are the signs of pregnancy induced hypertension among

women in Kabo Local Government Area of Kano State?

2. What are the risk factors associated with pregnancy induced

hypertension among women in Kabo Local Government Area

of Kano State?

3. What are the preventions measures of pregnancy induced

hypertension in Kabo Local Government Area of Kano State?

Literature Review

Pregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH) known as toxemia or

preeclampsia is a form of high Blood Pressure (BP) in pregnancy.

PIH is one developing after 20 weeks of gestation without other

signs of preeclampsia. It is a known cause of premature delivery,

intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), placental abruption and

fetal death, as well as maternal mortality and morbidity (Gombe

et al., 2011). It is characterized by either blood pressure levels

of 140/90 mm Hg or higher after 20 weeks of gestation, or a

blood pressure rise greater than 30/15mmHg from early or prepregnancy

baseline or a rise of mean arterial pressure of more

than 105 mmHg. This due to the development of arterial high

pressure in a pregnant mother after 20 weeks of gestation, which

may or may not have protein in urine and has a blood pressure

of or more than 140/90 mmHg (National Guidelines for Quality

Obstetrics, 2004). Of all the pregnancy related complications in the

world, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia present 10% major causes of

maternal and prenatal morbidity and mortality, with pre-eclampsia

affecting 5-7 % of all pregnancies, Srinivas, et al. [15]. Hypertensive

disorders during pregnancy is among the leading cause of maternal

and fetal mortality in obstetric practice that can prevent the baby

from getting enough blood and oxygen harming their liver, kidney,

brain, and heart, causing end organ damage, Palacios, et al. [16].

Pregnancy induced hypertension is a major cause of maternal

morbidity and mortality in the United States. There is an

approximately one maternal death due to preeclampsia-eclampsia

per 100,000 live births, with a case-fatality rate of 6.4 deaths per

10,000 cases Livington, et al. [17]. The outcome of hypertension in

pregnancy is affected by multiple factors. These include gestational

age at onset, severity of disease, and the presence of comorbidities

like diabetes mellitus, renal disease, thrombophilia, or pre-existing

hypertension Heard, et al. [18]. Similarly, a study conducted in

Latin America and Caribbean, Pakistan, New York, and Sri Lanka

identified null parity, multiple pregnancies, history of chronic

hypertension, gestational diabetes, fetal malformation and obesity

as the risk factors for developing pregnancy induced hypertension

Dolea [19]. Furthermore, life-threatening maternal age (less than

20 or over 40 years), history of PIH in previous pregnancies, preexisting

diseases like renal disease, diabetes mellitus, cardiac

disease, unrecognized chronic hypertension, positive family history

of PIH, which shows genetic susceptibility, psychological stress,

alcohol use, rheumatic arthritis, very underweight and overweight,

and low level of socioeconomic status are the risk factors for PIH

Abeysena, et al. [20].

One important aspect of diagnosing and managing hypertension

in pregnancy is presiding out secondary causes. These causes can

add to both the maternal, fetal morbidity and mortality. Records

from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) of hospitalizations for

delivery between 1995 and 2008 showed that out the patients with

chronic hypertension (1.15% of the sampled population), 11.2%

had secondary causes. Secondary hypertension had higher odds of

adverse maternal and fetal outcomes when compared to essential

hypertension (odds ratio (OR), 11.92 vs 10.18 for preeclampsia,

51.07 vs 13.14 for acute renal failure, 4.36 vs 2.89 for spontaneous

delivery < 37 weeks) Bateman, et al. [21]. Examples of secondary

forms of hypertension are chronic kidney disease (most common

cause), hyperaldosteronism, Reno vascular disease, obstructive

sleep apnea, Cushing’s syndrome, pheochromocytoma, thyroid

disease, rheumatologic diseases (e.g. scleroderma or mixed

connective tissue disease), and coarctation of the aorta; lack of

understanding on how to diagnose and treat these conditions

during pregnancy may lead to a higher morbidity and mortality

Malha [22].

Pregnancy Induced Hypertension in Nigeria

In Nigeria, an incidence of 20.8% of pregnancy induced

hypertension had been reported in a study of pregnant women

attending antenatal clinics in a Teaching Hospital in South-South

Ebeigbe, et al. [23]. Similarly, prevalence rates of hypertensive

conditions of pregnancy range from 17% to 34.1% Singh, et al.

[24]. In 2009, the occurrence of PIH ranges between 2% to 16.7%

Abubakar, et al. [25]. In 2011, Enugu town had 3.3% per 77 cases of

PIH out of 2337 cases Ugwu, et al. [26]. In 2014, according to Singh,

et al. [27], the prevalence of hypertensive disorders was estimated

to be higher than 17% in Nigeria. Akeju, et al. [28] suggested that

women have health seeking behaviors, which range from buying

over the counter drugs to relieve headache, consulting families

on what to do with odema, epigastric pain and blurred vision,

consulting a spiritual or traditional healer on convulsing and coming

to hospital. All these health-seeking behaviors may delay coming to

hospital, worsening the PIH complications. Between the periods of

1990 and 2015, 10.7 million maternal deaths were stated globally,

in spite of the fact that maternal mortality ratio had fallen by 44%

over these periods. WHO [29]. Out of this total number, developing

countries accounts for about 99% of the global deaths in 2015, with

Sub-Saharan Africa accounting for bumpily 66%.

Study by WHO [29] showed that Nigeria and India are estimated

to account for over one third of all maternal deaths globally in 2015,

contributing 19% and 15% respectively. Furthermore, the study

also revealed that in the West African sub-region, Nigeria with a

maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 814 ranks second, after Sierra

Leone 1360 MMR. With this MMR, Nigeria could not meet the

MDG5A target in 2015, which aims to reduce maternal mortality

ratio by 75% of its 1990 level by 2015.Among the causes of maternal

mortality, hypertension ranks second (14%) after hemorrhage Say,

et al. [30]. In Nigeria, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy could

be a contributory factor to the rising prevalence of hypertension,

which has been predicted to escalate up to 39.1 million by 2030, if

the current inclination in figures continues Adeloye, et al. [31].

Empirical Review

Studies conducted by Butalia, et al. [32] and Regitz Zagrosek,

et al. [33] revealed that there remain terminology and definition

disagreements across international guidelines for hypertension.

Hypertension itself has been defined over the years by diastolic

or systolic readings alone, as well as by changes in pressures

throughout pregnancy Chappell, et al. [34]. Similarly, limits for what

is considered severe hypertension have been different. Semantics

have clinical implications, and systematic reviews often have

to compare studies or populations, which are assumed to be the

same, rather than standardized Abalos, et al. [35]. Therefore, the

International Society of the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy

(ISSHP) identified this as one of the factors for the range of

controversies surrounding the treatment of hypertension during

pregnancy and appointed a committee to address them beginning

in 1998 Brown, et al. [36]. Moreover, studying several international

guidelines, definitions are more standardized; however, there are

still disagreements in sphygmomanometer intervals that define

hypertension, precise definitions of proteinuria, the terms used

to characterize blood pressure in the non-severe range, and even

terminology used to classify the hypertensive disorders themselves

Redman [37,32,33]. All of these reflect that the understanding of

hypertensive disorders of pregnancy remains unsolidified and

further research is necessary before a universal unanimity is

reached on how to treat these disorders.

Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy (HDP) is defined as high

blood pressure during pregnancy, is one of the direct causes of

maternal and child mortality AOM [38]. It is measured by blood

pressure level greater than 140/90 mm Hg after 20 weeks of

gestation. Austere forms of HDP are reflected through blood

pressure intensities of 160/100 mm Hg and more NHLBI [39].

Furthermore, studies by Magee, et al. [40] revealed that HDP are

responsible for 70,000 maternal deaths globally, killing one woman

every 11 minutes. HDP is the second leading cause of maternal

mortality in Bangladesh, according to the Bangladesh Maternal

Mortality Survey 2017, with approximately 24 percent of the

country’s maternal deaths caused by pre-eclampsia/eclampsia

(PE/E) NIPORT [5], which affects women during pregnancy,

childbirth, as well as postpartum. Factors, such as lack of health

care provider capacities to detect, prevent, and manage PE/E, late

referrals of HDP clients, late attendance and lack of antenatal care

(ANC) and awareness about preeclampsia or eclampsia among

communities have been associated as reasons for most of these

preventable deaths Warren et al. [6].

Theoretical Framework

This study is anchored on two theories, which include: the

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned

Behavior (TBP). Theory of Reasoned Action was formulated by

Martin Fishbein and IcekAjzen towards the end of the 1960s. On the

other hand, IcerkAjzen proposed the Theory of Planned Behaviour

in 1985; which was an extension from the TRA. The Theory of

Reasoned Action and Theory of Behaviour Planned combine two

sets of belief variables, which are ‘behavioural attitudes’ and

‘the subjective norms’. The behavioural attitudes are defined

as the multiplicative sum of the individual’s relevant likelihood

and evaluation related to behavioural beliefs. On the other hand,

subjective norms are referent beliefs about what behaviors others

expect and the degree to which the individual wants to comply with

others’ expectations. The summary of the two theories suggest

that a person’s health behavior is determined by their intention

to perform a behavior (behavioural intention) is predicated by a

person’s attitude toward the behavior, and the subjective norms

regarding the behavior. The Theory of Reasoned Action has been

criticized because it is said to ignore the social nature of human

action Kippax [41]. These behavioural and normative beliefs are

derived from individuals’ perceptions of the social world they

inhabit, and are hence likely to reflect the ways in which economic

or other external factors shape behavioural choices or decisions.

In addition, there is a compelling logical case to the effect that

the model is inherently biased towards individualistic, rationalistic,

interpretations of human behavior. Its focus on subjective

perception does not essentially permit it to take meaningful

account of social realities. Individuals’ beliefs about such issues

are unlikely going to reflect the accurate potential and observable

social facts. As such, the Theory of Planned Behaviour updated the

Theory of Reasoned Action to include a component of perceived

behavioural control, which brings about one’s perceived ability to

enact the target behavior. Actually, perceived behavioural control

was added to the model to extend its applicability beyond purely

volitional behaviours. Previous to this addition, the model was

relatively unsuccessful at predicting behaviours that were not

mainly under volitional control. Therefore, the Theory of Planned

Behaviour proposed that the primary determinants of behaviour

are an individual’s Behavioural intention and perceived behavioural

control. A constructive use of the TRA and TBP in research and

public health intervention programmers might well contribute

valuably to understanding issues related to health inequalities and

the roles that other environmental factors have in determining

health behaviours and outcomes. In spite of the criticism, the

general theoretical framework of the TRA and TPB have been

widely used in the retrospective analysis of health behaviours

and to a lesser extent in predictive investigations and the design

of health interventions Hardema, et al. [42]. This is why there is a

connection between the study and the theory, since the tenets of

the theories are located within the pore of the study.

Methodology

The study was conducted in Kabo Local Government Area of Kano State, Nigeria. It has an area of 341km2 and a population of 153,828 NPC [43]. The study comprises of women within the reproductive ages of 14-45, pregnant and married in Kabo Local Government Area of Kano State. Women were purposively selected for the study not just because of their ability to conceive but they are the ones that do encounter pregnancy induce hypertension. Two nurses were selected from the Cottage Hospital in the local government based on their long working experiences and competencies in the facility. This makes a total sample of twenty one (22) respondents. The study used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). Purposive sampling method was used in selecting the respondents for in-depth interview. Kabo Cottage Hospital was purposively selected, which is bigger compare to other two in the local government with an average of 52Anti-natal Care Attendance (ANC) and 36 live births in the facility monthly. The 22 respondents were interviewed by structural interview method, using tape recorder, note book and biro as data gathering instruments. The respondents were tag with codes like respondent 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, etc. Based on the in-depth interview method, the data was presented using interpretative analysis.

Findings and Discussion

In attempt to mention the signs of pregnancy induced

hypertension, respondent 1 states that: “signs of pregnancy induced

hypertension are many, however, she stated the following as part

of the signs as follows: chest pain and headache”. Corroborating,

respondent 2 put forward the followings as some of the signs:

“blurred vision and dizziness,” while respondents 3, 4, 5 and 6

agreed that pedal oedema and epitaxies are also among the signs.

Similarly, a study by Haque [44] stated that high blood pressure,

headache, blurred vision, swelling in extremities, nausea or

vomiting, fatigue and sudden weight gain are among the signs of

pregnancy induced hypertension. Furthermore, Magee, et al. [45]

noted that the patient with severe PIH should be evaluated for signs

of preeclampsia, as generalized edema, including that of the face

and hands, rapid weight gain, blurred vision or scotomata (ie, areas

of diminished vision in the visual field), throbbing or pounding

headaches, epigastric or pain associated with upper quadrant,

oliguria (urinary output < 500 mL/d),nausea with or without

vomiting, hyperactive reflexes, chest pain, tightness and shortness

of breath. Blood pressure should be measured and recorded at

every prenatal visit, using the correct-sized cuff, with the patient

in a seated position. Leeman [46] said gestational hypertension

is a clinical diagnosis confirmed and established by at least two

accurate blood pressure tests in the same arm in women without

proteinuria, with readings of ≥ 140 mm Hg systolic and ≥ 90 mm

Hg diastolic.

It should then be determined whether the patient’s

hypertension is mild or severe (i.e. blood pressure > 160/110 mm

Hg). When asked about the risk factors associated with pregnancy

induced hypertension, respondent 1 states that: “parts of the

risk factors associated with pregnancy induced hypertension are

indefinitely large numerically, nonetheless, she listed the followings

as part of the risk factors: “multiple gestations, elderly prim gravida

and high parity.” Moreover, respondent 2 stated “polyhydramnios

and essential hypertension,” while respondent 3 stated “kidney

disease.” All the respondents agreed that high salt intake (in diet),

obesity and stress also contribute to the risk factors associated

with pregnancy induced hypertension. Bansode [47] also found

that some of the factors associated with pregnancy induced

hypertension include first pregnancy, new partner/paternity, age

<18 years or >35years, black race, obesity (Body Mass Index, BMI

≥ 30), inter-pregnancy interval <2 years or > 10 years and use of

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) beyond the first

trimester; while placental or fetal risk factors include multiple

gestation, hydropsfetalis, gestational trophoblastic disease and

triploidy. Similarly, Umegbolu [48] reported that the overall

incidence of PIH among pregnant women in Enugu State, Southeast

Nigeria (2006-2015) was found to be 5.9%.

The study identified annual variations in the incidence of PIH

(rising and falling trends between 2006 and 2015) among the

pregnant women. The incidence of PIH was highest among those

women above 35 years (13.5%), compared to those whose age is

less than 20 years (9.1%) and those between 20-35 years (5.1%).

The occurrence was also higher in the nulliparous (prim gravidae)

(7.7%) compared to the multiparous ones (5.5%). Furthermore,

Anujeet, et al. [49] stated that hypertension, collagen vascular

disease, obesity, black race, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus,

gestational diabetes, increased serum testosterone concentrations

and thrombophilia, clotting disorders, and hemolysis, elevated

liver enzymes, low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome are also

responsible risk factors for PIH. Similarly, age and parity are two

of the identified maternal risk factors for the development of

pregnancy induced hypertension. Extreme ages (age below 20

years and above 35 years) are known to be associated with higher

incidence of pregnancy induced hypertension. Like the overall

incidence of pregnancy induced hypertension, incidence among

various age groups and parity varies from place to place. In Karachi,

Rehman, et al. [50] found an incidence of 9% among older women

and 27% among prim gravidae. However, Sajith, et al. [51] reported

an incidence of pregnancy induced hypertension of 41.3% among

18-22 years old patients in their study.

Furthermore, Ahmed, et al. [52] states that educational

attainment of women is also a factor that contributes to developing

pregnancy induced hypertension. This is because illiterate mothers

are more likely to suffer from hypertension during pregnancy

than their counter parts. There is every tendency that educated

mothers are likely to be aware of pregnancy related complications

and its consequences, marry educated husband that facilitate

couples discussion on maternal health care utilization, likely

to be autonomous in decision making and hence meeting her

reproductive needs. Generally, education increases health seeking

behaviours of women. The study of Swati, et al. (2014) stated being

unmarried as a risk factor and prognosticator of PIH, which is an

exceptional result from this study. The study further explains that

although marital status is hardly reported as a risk factor in the

literature, a possible explanation in a resource poor country like

Nigeria could be due to worry about the financial burden of single

parenting in environment, which lacks any form of child welfare

support. Moreover the stigma of having a child outside marriage is

a potential source of concern and anxiety. In addition, Zusterzeel,

et al. [53] had emphasized immunological intercourse as the

prevention of this maternal-fetal conflict called pregnancy induced

hypertension. There is an association of pregnancy-induced

hypertension with duration of sexual co-habitation before the first

conception. Male ejaculation is said to protect a woman if she has

been repeatedly been exposed to it.

Regarding the prevention and management of pregnancy

induced hypertension, respondent 10 states that “regular antenatal

care and regular check-up/ BP checking are sine qua non.”

Corroborating, all the respondents agreed that low salt intake,

avoiding alcohol, regular intake of water drug therapy for severe

hypertension, treatment of underlying medical conditions like

kidney problem and avoidance of strenuous exercises or stress are

parts of the prevention and management. The findings of the studies

are similar with Singh [54] that PIH can be prevented and managed

by low salt intake, drinking at least eight glasses of water a day,

regular BP check-up, increase the amount of protein-rich foods and

decrease the amount of fried and junk foods, regular exercise and

enough rest, elevate your feet several times during the day, avoid

drinking alcohol and beverages containing caffeine, prescription

of drug therapy and additional supplements by a medical doctor.

In drug management of pregnancy induced hypertension, ACOG

[55] states that labetalol and extended-release nifedipine are

first line drugs as they are safe and effective. Similarly, Morgan, et

al. [56] emphasized, although beta-blockers other than labetalol

are less well investigated, if labetalol cannot be used metoprolol,

propranolol, pindolol and acebutolol may be considered. Extendedrelease

nifedipine is the most widely used calcium channel blocker.

Amlodipine has been used, but the data are limited. Inhibitors

of the Renin Aangiotensin Aaldosterone System (RAAS) are totally

contraindicated. This includes angiotensin converting enzyme

(ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and direct

renin inhibitors. The package insert of these agents comes with a

black box warning stating that usage during the second and third

trimesters can cause injury and death to the developing fetus;

therefore, discontinuation is indicated as soon as pregnancy is

detected. RAAS inhibitors use in the second and third trimesters

is associated with renal agenesis, pulmonary hypoplasia and

intrauterine growth retardation, IUGR. The proof of fetal injury

during first trimester exposure is unclear. Post-delivery lactating

mothers may use enalapril, captopril or quinapril because they have

low concentration in breast milk; labetalol may be continued only in

lactating mothers Colaceci [57]. In addition, Donovan [58] says the

choice of antihypertensive drugs to be used depends on whether

breastfeeding is tried or attempted. When the woman desires to

breastfeed, deliberation must be given to potential transfer of the

drug into breast milk. This is due to the established evidence that

most drugs safely used in pregnancy are excreted in low amounts

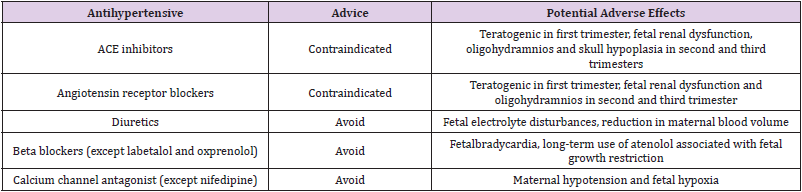

into breast milk and are compatible with breastfeeding. (Table 1)

shows antihypertensive drugs of those to use and those to avoid

during lactation.

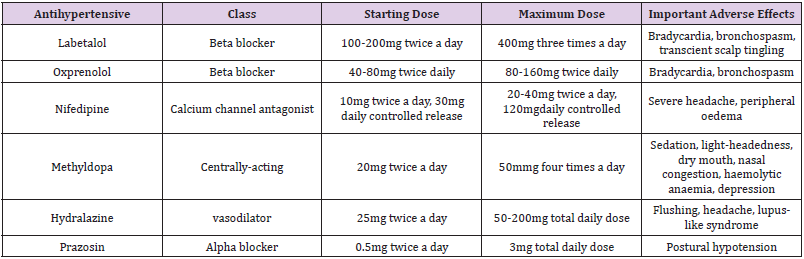

In an instance when there is no desire to breastfeed and adequate contraception is used, the choice of antihypertensive drug is the same as for any other non-pregnant woman or patient. While (Table 2) shows the antihypertensive drugs used in pre-eclampsia, which are the same as those used to treat chronic and PIH Lowe et al. [59-61].

Conclusion

The strains of maternal mortality remain unduly borne by

women in less-developed countries, particularly in sub-Saharan

Africa. Between the periods of 1990 and 2015, 10.7 million

maternal deaths were stated globally, in spite of the fact that

maternal mortality ratio had fallen by 44% over these periods. Out

of these total numbers, developing countries account for about 99%

of the global deaths in 2015, with Sub-Saharan Africa accounting

for bumpily 66% with 201,000 deaths. PIHs are responsible for

70,000 maternal deaths universally, killing one woman every 11

minutes. Nigeria, in 2014, recorded the prevalence of pregnancy

induced hypertension and was estimated to be about 20.8%

among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Teaching

Hospitals in South-South. Based on these problems, the findings of

this study attest that the signs of pregnancy induced hypertension

in Kabo Local Government include chest pain, headache, blurred

vision, dizziness, pedal oedema and epitaxies. Finally, the risk

factors are multiple gestations, elderly prim gravida, high parity,

polyhydramnios, essential hypertension, kidney disease, high salt

intake (in diet), obesity and stress.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.