The Diagnostic Difficulties and The Delayed Identification of Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma in A Teenage Patient. A Review of Literature

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) originates from peripheral T-lymphocytes and is the most common mature T-cell neoplasm in children and adolescents. All in all, these neoplasms are relatively rare among all types of lymphomas. ALCL comprises about 10-20% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) in the above group of patients [1-3]. Essentially, this lymphoma does not occur frequently and is often difficult to distinguish, though its identification is essential for both the prognosis and treatment [4]. The primary site of the lymphoma can appear in almost any location, including lymph nodes. This may result in unspecific clinical signs of disease leading to why it can take several months from the appearance of the first symptoms to make an accurate diagnosis.

ALCL was recently classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as primary cutaneous ALCL (C-ALCL) and systemic ALCL (S-ALCL). The second category was further divided into two distinct types based on expression of a protein called anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), ALCL ALK-positive (ALK+) and ALCL ALKnegative (ALK-) [5]. The presence of this protein on neoplastic cells is more frequent in children and young adults, with a median age of approximately 30 years, whereas the lack of it is proven in older adults (median age of about 55 years). Simultaneously, this feature is associated with improved overall survival [2,6,7]. Additionally, the assessment of ALK expression plays an essential role in the case of S-ALCL. The overall survival rate of ALK+ lymphoma increases up to 70% and is far better that of ALK- lymphoma that ranges from 15-45% [6,7]. C-ALCL is marked by indolent development and a favorable prognosis with a survival rate of 80-95% [2]. We present the case of a patient with an unusual clinical manifestation and difficulties in the diagnostics of S-ALCL. We would like to point out what to do in order to avoid mistakes in the early stages of this disease. Additionally, attention should be paid to the aggressive and insidious growth of S-ALCL in a very brief time.

Case Presentation

Patient History and Information

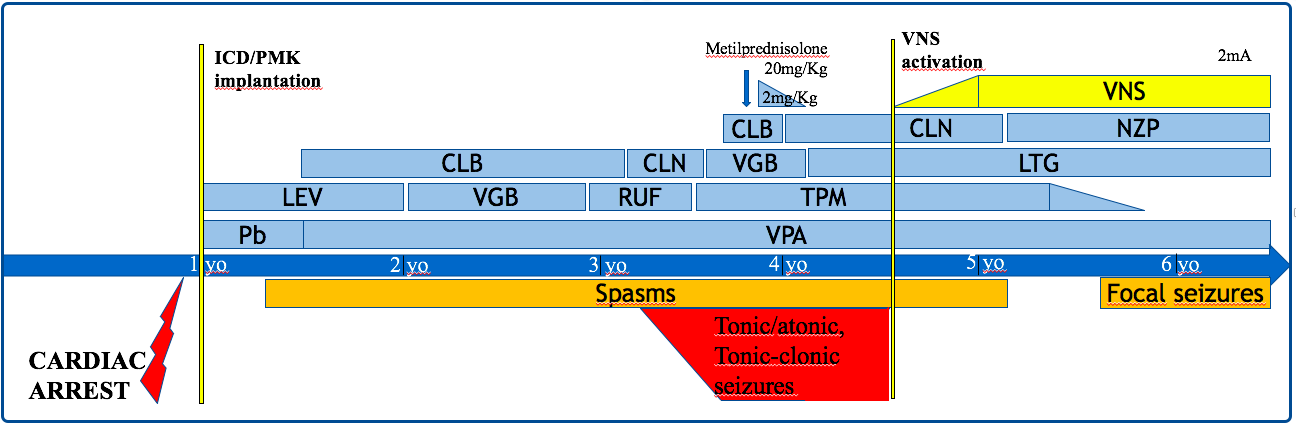

A sixteen-year-old boy was admitted to the Surgery Clinic in July 2017 due to a nodular skin lesion. The 4 cm lesion was located in his lower abdomen and was darker than the surrounding skin. On clinical examination, the lesion was suspected to be an abscess and the patient was sent to surgery. The lesion was incised and did not contain any liquid content. No tissue material was taken for histopathological examination. The wound did not heal, was suppurating and slowly reducing its size. Furthermore, in August 2017, hard and painless tumors appeared in the area of both groins. Ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) of the abdominal cavity and pelvis showed enlarged lymph nodes in the inguinal and pelvic regions. Based on the above examination, lymphoma was suspected, and the boy was sent to the Department of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology and Transplantology at Poznan University of Medical Sciences.

Diagnostic Assessment

On the day of admission in September 2017, the physical examination showed an unhealed wound on the skin of the lower abdomen and palpable hard nodal masses in the iliac fossae. We have only a photographic evidence of the scar 4 months after surgical treatment (Figure 1). Additionally, a painless fistula with leakage was observed inside the oral cavity in the area of the right molar teeth. The liver and spleen were not enlarged. The results of biochemical tests, morphology, and peripheral blood smears were within normal limits. During his stay in the Department, the patient presented with a low-grade fever and increasing facial asymmetry caused by swelling of the right cheek. CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head revealed the solid mass (60x42x35 mm) filled almost all of the space of the right maxillary sinus and destroyed the structure of the posterior wall of the sinus, invading the pterygopalatine fossa and adipose tissue, reaching the area of the masseter muscles. Laterally, it was spreading into the right buccal area where from the medial side, it was infiltrating the lateral part of the palate. Upwards, it was penetrating the inferior orbital fissure and damaging the upper wall of the maxillary sinus into the right orbit. There were no signs of the tumor spreading to the middle cranial fossa. Furthermore, numerous enlarged lymph nodes of the upper neck region were found. Biopsies of the inguinal node, exophytic craniofacial tumor, and bone marrow along were performed. The patient was also examined with positron emission tomography (PET), which allowed for a determination of disease in stage IV.

Histopatological Findings

Materials and Methods: The specimen was taken from three different sites and sent to Pathology Department. The first surgery consisted of excisional biopsy of enlarged, inguinal lymph node. 5 days later the biopsy of bone marrow (two trephines) was done. 6 days later excisional biopsy of two tumors in the oral cavity, (including right maxilla and oral vestibule) was performed. All resected specimens were fixed in 10 % buffered formalin, routinely processed and embedded in paraffin, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. An initial panel of immunohistochemical stains was performed on an automated immunostainer (Ventana Benchmark, Roche/Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) and this included: CD30, EMA (Epithelial Membrane Antigen), ALK-1, CD43, CD3, CD15, CD20, Desmina (DES), CD25, Granzyme B, Perforin, TIA 1, CD7, CD5, Cd8, Cd56, MUM 1, PDL 1, CD4, CD2, EBI-1, PAX-5, Ki 67.

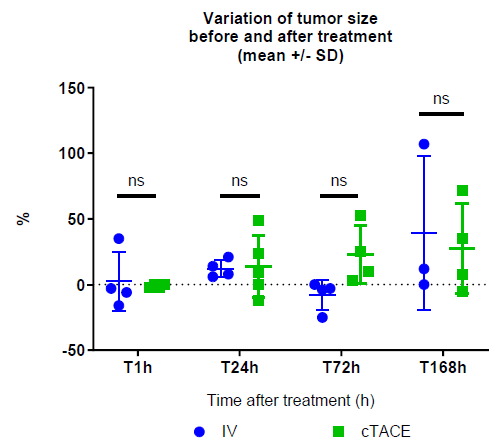

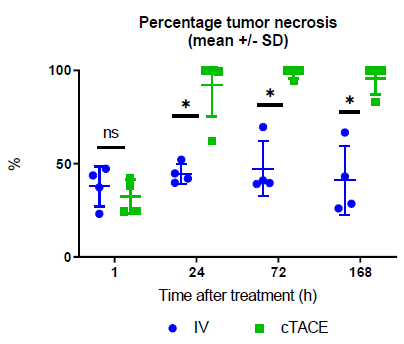

Results: Grossly, the first resected specimen consisted of

solid

soft tissue in form of a lymph node measuring 3,5 cm x 3,0 cm x

2,0 cm. It was oval in shape, but the external surface was rather

smooth. On cross section, the tumor was white to grey, solid

and encapsulated. The second specimen consisted of two core

biopsies specimen of bone marrow measuring 2,6 cm and 0,8 cm

in length. The third specimen from the oral cavity consisted of two

separated specimens each of which was fragmented measuring 5

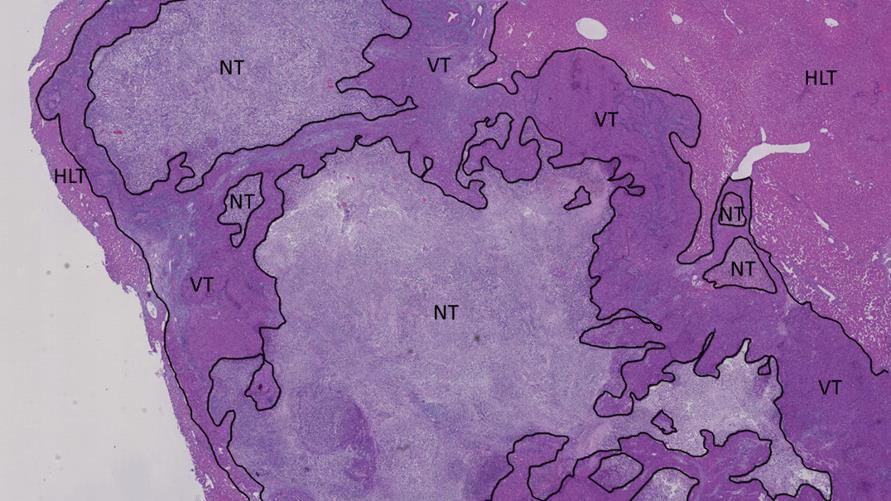

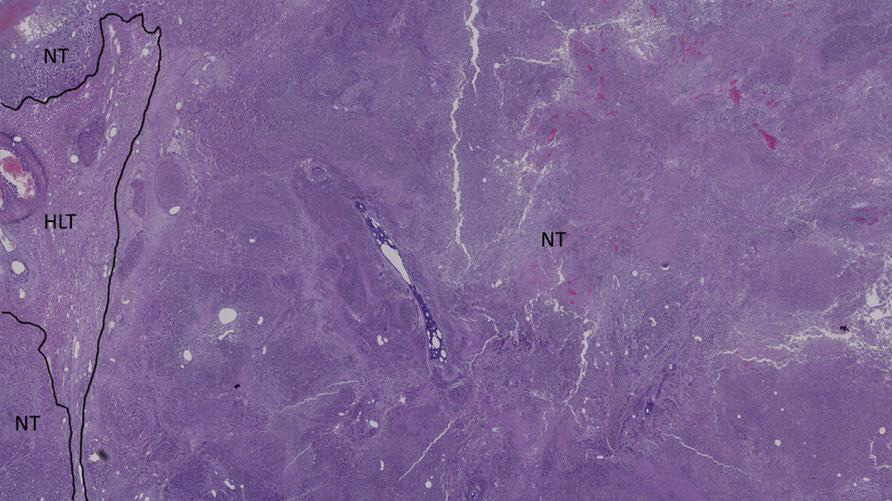

cm and 3 cm respectively in greatest diameter. Microscopically, the

neoplasm invaded the lymph node and the specimens from oral

cavity. The bone marrow specimen was not impaired. The tumor

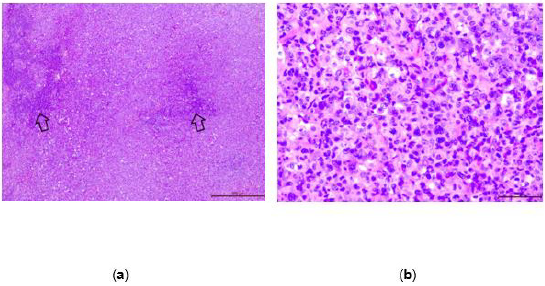

cell occupied almost entire parenchyma of the lymph node (Figure 2a).

The neoplastic cells differed in size from small to large ones

(Figure 2b). This was helpful in distinguishing ALCL from Hodgkin

Lymphoma. The cells invading the lymph node and the oral cavity

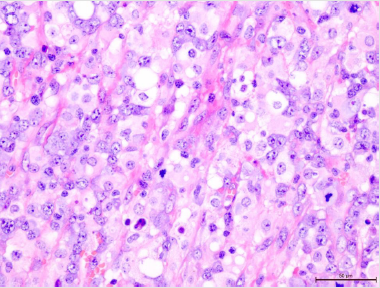

had the same morphology (Figure 3). Most of the neoplastic cells

were large, irregular and bizarre. They often had polylobated nuclei

and the subset of cells had eccentric horse- or kidney-shaped nuclei

consisted with Hallmark cells characteristic of ALCL. Admixed with

the tumor were scattered small lymphocytic cells. Mitotic figures

were easily encountered (60 per 10 high power fields). There was

no necrosis.

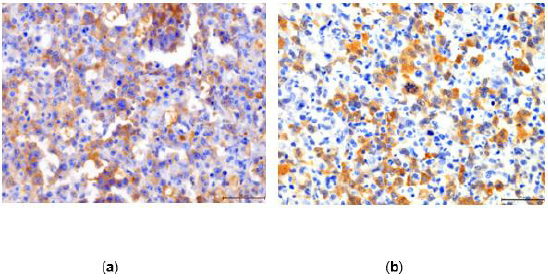

Immunohistochemically the tumor cells stained for CD 30 and

ALK 1 showing nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (Figure 4a and

4b). Such pattern of staining correlates with underlying genetic

abnormality t (2;5). They also stained for EMA, CD43, CD25,

Granzyme B, Perforin, TIA 1, Ki -67 in 80% of the cells and focally

for CD3, CD7, CD5, CD8, CD56, MUM 1, PDL 1. They neoplastic cells

were negative for CD15, CD20, Desmin, CD4, CD2, EBI-3, PAX 5.

The microscopic and immunophenotypic studies confirmed the

diagnosis of Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, common type.

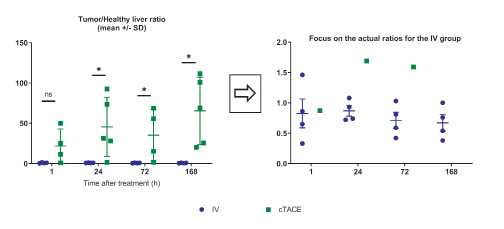

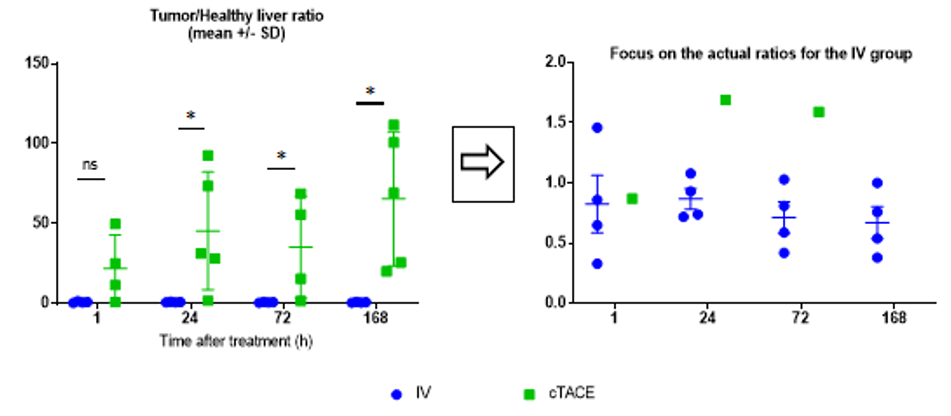

Figure 2: (a) The tumor invades almost entire inguinal lymph node tissue. There are only small areas of the normal lymph node (arrows), H&E, 200X; (b) The neoplastic cells range from small to large ones. They usually have large, irregular, and bizarre or polylobated nuclei, H&E ,400X.

Figure 4: (a) The tumor cells are diffusely positive for CD30, 400X; (b) Most of the neoplastic cells stain for ALK 1, 400X.

Diagnosis

Based on the PET scan and pathology report, ALCL in stage IV was diagnosed.

Treatment and Outcome

After establishing the final diagnosis, treatment according to the international protocol ALCL 99 was started. It consisted of six alternating, consecutive courses of AM (dexamethasone, methotrexate, ifosfamide, cytarabine, etoposide) and BM (dexamethasone, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin) [8]. Currently, the patient remains in the first complete remission of the disease, 36 months after their treatment.

Discussion

S-ALCL remains a moderately aggressive lymphoproliferative

neoplasm with worse outcomes than most B-cell lymphomas, yet

significantly better survival than other peripheral T-cell lymphomas

[9]. The majority of patients are male and present with advanced

disease in stages III or IV, often with systemic symptoms, especially

fever. Dissimilar from adults, ALCL in children usually demonstrates

expression of ALK [1,3,6,7]. The diagnosis of S-ALCL can be

challenging, mainly when first signs appear in the skin. One of the

reasons for this is that both types of S-ALCL can secondarily involve

the skin and C-ALCL can secondarily involve regional lymph nodes.

It shows the importance of the correlation of histopathological

findings with staging and other clinical data in order to establish

a proper diagnosis [9]. The stage of the disease at the beginning is

frequently determined as advanced. It may often result from both

a late diagnosis as well as a rather rapid developmental rate of

disseminated neoplastic cells. In literature, such cases take a few

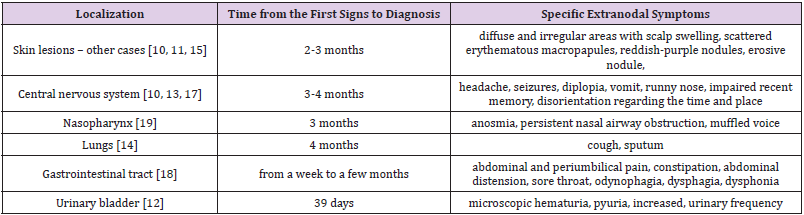

months from the first signs of disease (Table 1) [10-15]. In our case,

that period lasted three months.

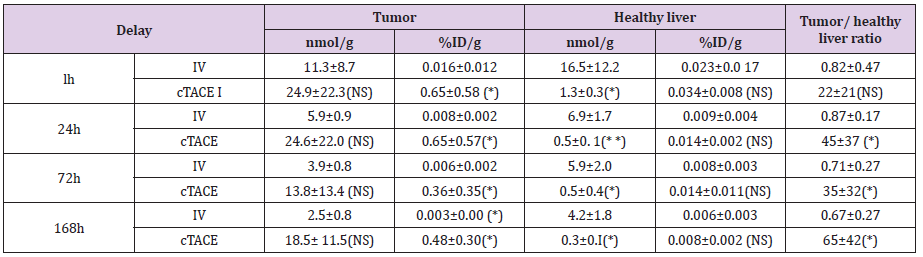

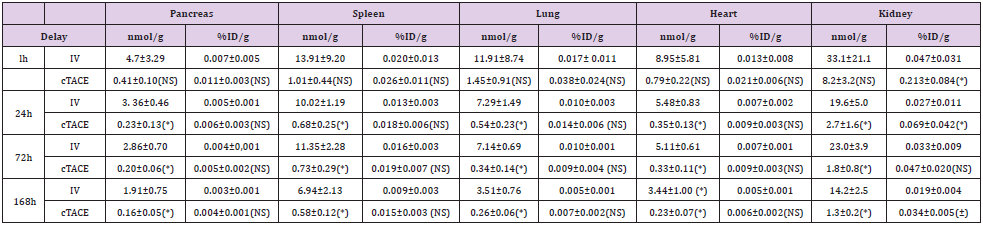

Table 1: The review of the approximate time from the first presenting signs to diagnosis and distinctive symptoms resulting from particular extranodal sites of ALCL in the literature.

The primary site of S-ALCL can occur in almost any location

in the human body. In most cases at first, it affects lymph nodes,

and the initial sign is painless lymphadenopathy. If that happens,

the proper procedure is to carry out a broad differential diagnosis.

We should take into account bacterial and viral infections, zoonotic

diseases, connective tissue diseases and neoplasms, notably

leukemia and lymphomas. In 60% of ALK+ anaplastic large cell

lymphomas, there is an additional involvement of extranodal

tissues most often concerning skin, bones, bone marrow, soft

tissues, lungs and liver [1,6,7]. However, S-ALCL presenting initially

as a localized skin lesion is an infrequent finding, as was the case

with our patient [11,15]. His first sign of lymphoma was a nodular skin

lesion that resembled an abscess. Other primary extranodal

localizations of S-ALCL are presented in literature, which include

soft tissues, lungs, bones, stomach, small intestine, tonsils, and the

central nervous system [13,16-18].

Symptoms resulting from extranodal involvement (listed in

Table 1) may imitate various other diseases and linking them to a

lymphoproliferative neoplasm can be quite challenging. Examples

of an atypical clinical course of ALCL can be found in literature

[10,11,13,14,19]. In cases of involved lungs, the lesion may present

as tuberous masses, atelectasis, displacement of the mediastinum

to one side and pleural effusion [14]. Sites in the central nervous

system are accompanied by various neurological disorders such

as diplopia, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness, persistent headaches,

impairment of recent memory, disorientation regarding the time and

place and poor state of mind [10,13]. Skin lesions can occur either

as a soft and swollen nodular lesion or as a scattered, erythematous

and maculopapular one, both of which can display ulceration [10,

11]. Moreover, a case of incorrect diagnosis of mononucleosis has

been reported in a teenage girl with a nasopharyngeal mass and

cervical lymphadenopathy where the mass caused nasal airway

obstruction [19].

Due to a wide range of complaints, patients may visit many

specialists in the early stages of disease. These physicians, who

are usually not oncologists, should keep oncological alertness in

every situation including trivial ones, as they play a particularly

important role in the initiation of the diagnostic process and referral

of patients to oncologists. The proper proceedings have a decisive

influence on prognosis, which also includes surgical interventions

of precarious lesions. For the described patient, a surgeon made

a significant mistake at the beginning of the diagnostic process.

Without any examination and histopathological analysis, the

doctor considered a nodular skin lesion as an abscess and incised

those changes to drain it. Thus, the time to make a diagnosis of

ALCL and initiating the treatment in the presented patient was

markedly protracted. The absence of any liquid content inside the

skin lesion should have led the physician to verify the previous

assessment. Moreover, he ought to have collected some material for

histopathological examination. What is more, the increased healing

time of this wound should have awaken the doctors’ suspicion of

the neoplastic character of this lesion.

Its histopathological features cause further difficulties

in diagnosing ALCL. The marked cellular pleomorphism and

morphologic variation of ALCL raises a broad differential

diagnosis including cancer, melanoma, sarcoma and other

hematopoietic neoplasms such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,

classical Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloid sarcoma and peripheral

T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified [20]. ALCL shows a

broad morphological spectrum. Still, all cases contain a variable

percentage of cells with eccentric, horseshoe- or kidney-shaped

nuclei, often with an eosinophilic region near the nucleus, socalled

hallmark cells [3]. It is essential to recognize that rare cases

may have subtle morphological features, including a prominent

reactive background [20]. ALK+ and ALK- types of S-ALCL

share similar morphological features and diagnosis cannot be

established based on morphological evaluation alone. Thus, the

immunohistochemistry and molecular profile (IHC) play essential

roles in the diagnosis and subclassification of ALCL [9]. The ALK+

form is associated with the NPM-ALK t (2;5) translocation, which

highly correlates with the identification of the ALK protein by IHC

[2]. CD30 antigen expression in the neoplastic cells is distinctive of

ALCL, but it is not a specific marker for this lymphoma. However,

the strong and homogenous staining helps distinguish ALCL from

other CD30+ lymphomas [6,9]. Besides being CD30+, most cases

also express epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Moreover, ALCLs

are considered peripheral T-cell lymphomas as they express one

or more T-cell antigens. Therefore, markers like CD2, CD4 and CD5

are positive in a significant proportion of cases. However, due to

the loss of several pan T-cell antigens, some cases may have an

apparent “null cell” phenotype [6,21]. S-ALCL is not one disease

entity, and the “one size fits all” treatment strategy is not ideal [8].

To implement the best targeted therapy, there is a necessity of an

exact determination of the neoplastic cells’ immunophenotype. In

view of the above, and due to additionally significant complexity

of histopathological diagnostics of lymphomas, this process should

be performed in the department of pathology with the highest

reference level. The facility should have all available diagnostic

techniques, beyond standard pathomorphological evaluation,

including but not limited to, broad antibody panels to IHC testing,

flow cytometry, cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics [22].

S-ALCL, especially in ALK+ peculiarities, exhibits chemosensitivity

in the front line and at relapse, leading to high response

rates with vastly different chemotherapy regimens [9,21]. The

beginning of the treatment based on an incorrect diagnosis may

cause the implementation of an incorrect chemotherapy protocol.

On the other hand, leaving the patient without any treatment

when the disease progresses very quickly can eliminate further

therapeutic options and lead to disastrous complications [22].

Results of the Savage et al. study showed that an advanced stage

and poor performance status are poor prognostic factors in both

ALK+ and ALK- ALCL. In contrast, multiple extranodal sites of

involvement and increased age are bad prognostic factors only in

the ALK+ type [6]. Implementation of targeted therapy at early

stages of disease may result in a better chance of recovery.

Conclusion

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas represent complicated diagnostic difficulties. The possibility of localization of both primary and secondary sites in extranodal locations makes clinical manifestation non-specific. Presented symptoms may seem trivial or can indicate another condition and as a result, can be easily marginalized. For this reason, it can lead to making a significant mistake at the beginning of the diagnostic process. Complicated pathomorphological diagnostics are based on immunophenotype evaluation with confirmation in the reference facility. As a consequence, ALCL is most often diagnosed in an advanced stage. Physicians who encounter such patients at the beginning are usually not oncologists. However, they are crucial to initiate the relevant diagnostic processes and refer the patient to the oncology center afterward. It is therefore essential to stay alert all of the time. Whether the patient will survive, improve and recover is their responsibility.

For more Articles on : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/