Sexual Satisfaction Among Slovenian Population

Introduction

Partnership not only satisfies the basic needs of the individual as a social being, but also contributes to health, positive interpersonal relationships, self-confidence, good self-esteem, and general well-being [1,2]. Sexuality is also crucial for good partnership and an important part of the human life cycle [3-5]. Sexual orientation is a predisposing characteristic of a person who is sexually attracted to persons of the same and/or opposite sex. Sexual orientation refers to the gender to which a person is emotionally, physically, sexually, and romantically attracted. It is primarily assessed through personal evaluation and reporting of whether one is attracted to a man or a woman [6,7]. Engaging in sexual relationships with persons of the same or opposite sex most often determines a person’s sexual orientation. Factors that influence whether a person has sex with a person of the same or opposite sex include availability of a partner, moral relationships, social norms, curiosity, need to fulfill the role of a parent, financial motives, etc. [8].

In sexuality it is necessary to separate the masculine and feminine sides. Men are more pragmatic beings, while women are more tactile beings. Therefore, an embrace is of great importance for a woman’s perception of sexuality, as the release of serotonin, dopamine and oxytocin then increases. A woman, who is otherwise a hyperdynamic being and has all her senses constantly activated, usually closes her eyes when kissing. This activates the depilation of the basic system of the visual sense, with which we reach the maximum information capacity of up to 90% [9]. Therefore, the aim of the study was to assess sexual satisfaction in the general Slovenian population using an adapted but modified questionnaire, which was suitable for identifying differences in sexual satisfaction between different variables.

Methods

The study was conducted on female and male participants via online survey. The online survey began in July 2020 and was completed in September 2020. The research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed of the aims and anonymity in writing before the study began. Informed consent was given by clicking the “Proceed with questionnaire” button. The National Ethics Committee approved the study design (No. 0120-200/2020/6).

Recruitment was based on the following inclusion conditions:

(a) Age of 18 years and older, and

(b) Personal consent to the questionnaire.

Participants with mental and sexual disorders were also included in the study. All participants were asked for demographic data: gender, age, marital status, education level, sexual orientation, number of children, number of all lifetime sexual partners, number of current sexual partners, number of sexual contacts per month, diagnosed mental and/or gynecological disorders and, for women, the number of archived orgasms during a sexual contact.

A validated questionnaire from Stulhofer, et al. [10] was used with some adaptations that allowed the questionnaire to be completed by both sexes. Linguistic validation of the questionnaire was done by translating it from English to Slovenian and vice versa. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient showed adequate internal consistency (α=0.963) for all statements. Based on the theoretical content relationship, we grouped certain statements into new cushions/variables:

My mood before sexual intercourse/activity (α=0.936):

• My sexual arousal toward a partner.

• Rate your sexual desire toward a partner

• My sexual response to a partner

• The intensity of my sexual arousal

My mood during intercourse/sexual activity (α=0.854):

• My emotional engagement during sexual activity.

• During sexual activity, I give myself to sexual pleasure

• The intensity of my orgasms

My partner’s mood during intercourse/sexual activity (α=0.936):

• Rate your partner’s sexual activity

• My partner gives in to sexual pleasure

• The way my partner is responsive to my sexual needs

• My partner is sexually creative

• My partner is sexually available

My balance in sexual intercourse/activities (α=0.857):

• Rate the appreciation of the pleasure I give to my partner.

• The variety of my sexual activities

• The frequency of my sexual activities

• The balance between what I give and what I get during sexual activity

• And the autonomic variable:

• My mood after sexual activity.

The modified questionnaire consisted of demographic data and 17 statements. A 5-point Likert scale was used for each statement, ranging from “not at all satisfied” to “extremely satisfied.” Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 statistical software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test were applied to determine whether the values had a Gaussian distribution and to choose between parametric and nonparametric statistical tests. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test showed a non-normal distribution. Based on this result, a non-parametric statistical analysis was chosen, namely Pearson’s correlation coefficient and χ2 -test. The statistical significance was set at p ≥ 0.05.

Results

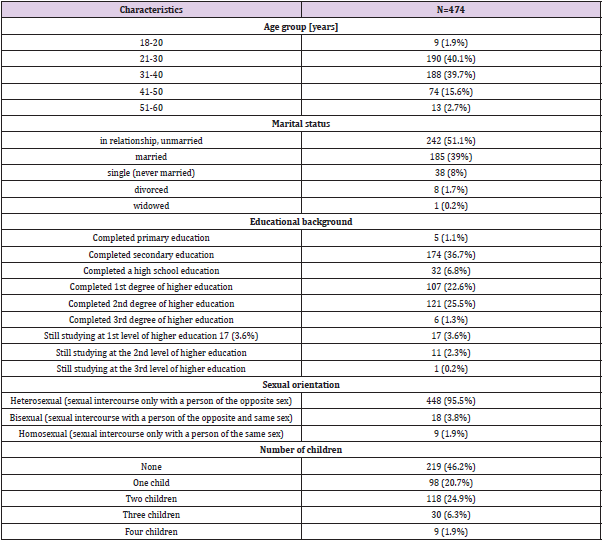

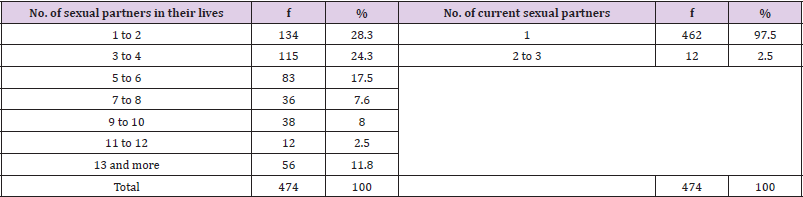

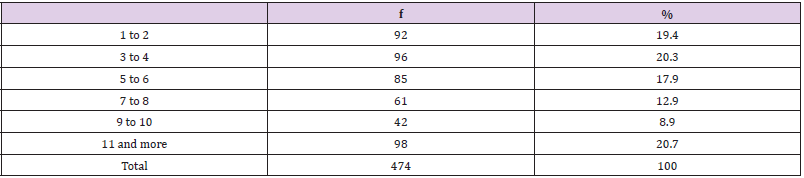

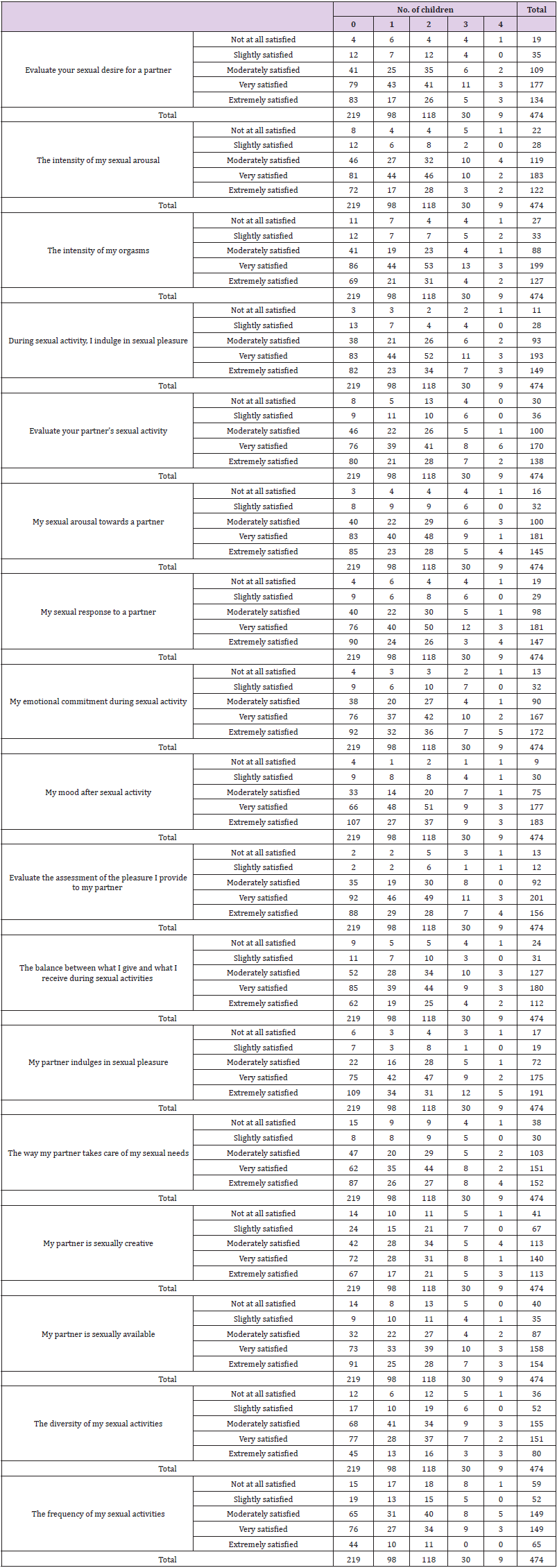

A total of 1418 questionnaires were received, of which 474 were fully completed. The realization of the sample was 33.43%. The sample included 405 female (85.4%) and 69 (14.6%) male participants. The basic demographic data are presented in Table 1. Participants were asked about the total number of sexual partners in their lifetime (Table 2). Most had one to two (n=134; 28.3%). Regarding the number of current sexual partners, respondents had one (n=462; 97.5%) or two to three (n=12; 2.5%) sexual partners (Table 2). In addition, the majority of participants had 11 or more (n=98; 20.7%) sexual contacts per month (Table 3). The female representatives were additionally asked about the number of orgasms during sexual intercourse. Most achieved two (n=178; 37.6%), three (n=110; 23.2%), one (n=69; 14.6%), and four or more (n=50; 10.5%) orgasms. Thirty-one (6.5%) participants did not have an orgasm, and 36 (7.6%) responses were missing. Twentysix (5.5%) participants were diagnosed with a mental disorder and 14 (3%) with a gynecological disorder. These individuals were also included in the study as we were interested in finding possible correlations.

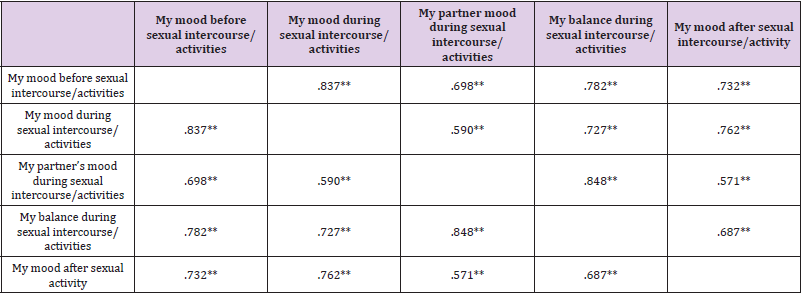

Based on Pearson correlation coefficient, strong correlations were found between mood before intercourse/activities and mood during intercourse (r=0.837), balance during intercourse/activities (r=0.782), mood after intercourse/activities (r=0.732) and partner’s mood rating during intercourse/activities (r=0.698). There were also correlations between mood during intercourse/activities and mood afterwards (r=0.762), balance during intercourse/activities (r=0.727), and rating of partner’s mood during intercourse/ activities (r=0.590). And between rating partner’s mood during intercourse/activities and balance during intercourse/activities (r=0.848) and mood after intercourse/activities (r=0.571) (Table 4). Female representatives were associated with partner mood and balance within sexual activity (Table 5). Male representatives showed no correlations with any of the cushions. In addition, correlations were found between an age group of 21 to 30 years and mood before, mood during, partner’s mood during, and balance during sexual intercourse/activities (Table 6).

Discussion

Although there are quality of life questionnaires that include questions about sexual satisfaction in the context of chronic disease, there is not much evidence of questionnaires that fully capture sexual satisfaction in the general population. Previous analyses included more women and examined the influence of menopause, body image, psychological distress from chronic disease, discomfort with sexual intercourse, and satisfaction with sexual intercourse. However, as far as we know, there is no questionnaire that includes different variables that could also influence men’s sexual satisfaction. Therefore, the aim of this study was to modify the already established questionnaire to more accurately capture the variables that have an impact on sexual satisfaction, in this case in a general Slovenian population. In our analyses, we included the general population of men and women and even individuals with mental and/or gynecological disorders. The questionnaire was adopted from Stulhofer et al. (2009) and modified to fully capture the sexual satisfaction of men and women from our population.

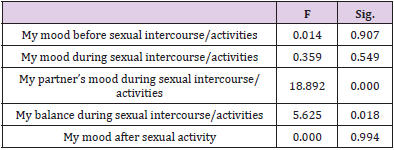

Based on the achieved reliability of the questions and results, we believe it can be used as a simple tool for clinicians in daily practise to facilitate communication about sexual satisfaction. Examination of correlations between general parameters such as gender, marital status, number of children, sexual intercourse per month, orgasms per activity and dependent variables for sexual satisfaction such as mood before, during and after intercourse and balance within intercourse showed interesting results. Satisfaction correlated well with mood before, during, and after sexual activity and, more importantly, with balance within intercourse. Important here are the questions that measure balance within sexual activity: ‘rating how much pleasure I give my partner’; ‘variety of my sexual activities’; ‘frequency of my sexual activities’; and ‘balance between what I give and what I receive during sexual activities’. This clearly shows that sexual satisfaction depends on the correlation with the activities of the participants and their partners during sexual intercourse. This was even confirmed by the correlations between female representatives and their partner’s mood (F=18.892; p 0.001) and balance during intercourse itself (F=5.625; p=0.994).

In several studies by Basson (2000, 2005, 2015) [11-13], the authors showed that women’s sexual desire is highly dependent on current relationship and partner dynamics, proving that women’s motivation for sexual intercourse does not necessarily arise from sexual desire, but is likely determined by the relationship [14- 17]. In addition, the results of our study proved that previous experience with more sexual partners, higher number of monthly sexual intercourse and orgasms, and younger age were associated with better sexual satisfaction. In addition, participants with more children showed lower sexual satisfaction. Having more children could affect sexual activity and thus sexual satisfaction. Intimacy is an important factor for women with children. The presence of children lowers the level of intimacy as women begin to ignore their sexual arousal because they focus primarily on the children and the family relationship [18,19].

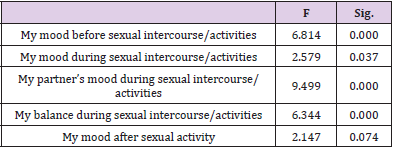

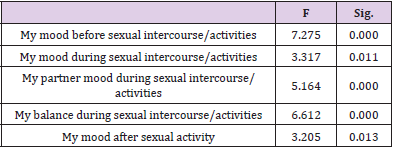

Both were evident in our study, as participants without children were the most satisfied with their sex lives, followed by participants with only one or two children. Satisfaction decreased with the number of children, such that participants with three or four children were the least satisfied with their sex lives. In addition, there were statistically significant correlations between participants who had no children and mood before, during, and after sexual intercourse, partner mood during and after sexual intercourse (both p=0.001), and mood after sexual activity (p=0.013). In addition, Dewitte, et al. [20] showed that the situation of not having children increases sexual activity in women and even decreases the negative effect of sexual desire on sexual activity. Sexual satisfaction was also associated with the age of the participants. Age from 21 to 30 correlated with mood before and during intercourse, mood of partner during intercourse, and balance during intercourse. Increasing age is associated with lower quality of life [21] and therefore could also affect sexual aspects of life, such as number of intercourses per month, number of orgasms, and overall satisfaction.

However, there is a contradictory variable that could affect sexual satisfaction. Namely, in our study, the number of sexual partners also showed a correlation with satisfaction. In this case, we would expect older participants to have better sexual satisfaction than younger ones, but this was not the case. One reason for this is the specificity of the questionnaire we used in our study. The questionnaire specifically addressed sexuality and sexual activity rather than overall quality of life. A middle-aged person may have a higher quality of life than a person aged 21 to 30 because their life priorities lie elsewhere. Here we have not come across the financial influences, career, family and social status. These are all factors that significantly affect the quality of life. On the other hand, life experience in sexuality, as people learn more about their sexual preferences or those of their partner over the course of their lives, could also be an interesting influencing factor on sexual satisfaction. This is suggested by the study of Forbes, et al. [21], who found opposite results when examining sexual quality of life with age.

They observed a positive relationship between age and sexual quality of life. Accordingly, for older participants, the quality - rather than quantity - of sexual encounters was a more important predictor of higher sexual satisfaction. In our study, we did not specifically measure quality per se, but attempted to estimate quality based on pleasure, number of sexual encounters, and orgasms. This could be the reason why younger participants experience better sexual satisfaction than participants in older age groups. The number of sexual encounters became less influential with age [22]. However, in both reports, age was associated with a decrease in sexual aspects of life. Our modified questionnaire was informative enough, showed good reliabilities of variables of significantly above 0.8, and can potentially be used in daily clinical practice.

However, there were limitations in this study. Despite the large sample size, the questionnaire should be validated in further studies to obtain additional information about the reliability of the questions. Also, more comparisons should be made between different parameters such as gender, marital status, and sexual orientation to gain truly meaningful insights into the variables that influence sexual satisfaction. In addition, a larger sample of men should be included in the future, as the results cannot be generalized to the general population due to the predominantly female participants. As this study was designed as a pilot study, we intend to conduct further analysis and gather further insights as we consider the questionnaire to be meaningful enough.

Conclusion

The present study provided the results that previous experience with more sexual partners, higher number of monthly intercourse and orgasms, and younger age were associated with better sexual satisfaction. In addition, participants with more children showed lower sexual satisfaction. In addition, a newly modified questionnaire was used for the first time to assess sexual satisfaction in male and female representatives. The questionnaire was evaluated and can be used in clinical practice to assess the level of satisfaction with sexual life. By measuring sexual satisfaction using mood pillow ratings, the questionnaire is a suitable tool for further evaluation and for a larger sample to obtain additional data on factors that might influence sexual satisfaction.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.