Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis and Apparent Density of Tsetse Fly in Botor Tolay District, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia

Livestock are the main stay of the vast majority of African people. They contribute a large proportion of the continent’s gross domestic product and constitute a major source of foreign currency earning for a number of countries. Trypanosomosis is among the well-known constraints to livestock production in Africa as it causes a serious and often fatal disease of livestock mainly in the rural poor community and rightfully considered as a root cause of poverty in the continent. Despite the importance of livestock to the larger sector of the population and to the economy at large the sub sector has remained untapped Vreysen [1]. It is the main haemoparasitic disease in domestic animals and is caused by the protozoan parasites of the genus Trypanosoma. A major determinant of the distribution and epidemiology of bovine trypanosomosis is the availability of suitable habitat for tsetse.

Tsetse are restricted to various geographical areas according to habitat, the three main groups, named after the commonest species in each group, being fusca, palpalis and morsitans, found respectively in forest, riverine and savannah areas. The last two groups, because of their presence in the major livestock rearing areas, have a great importance in veterinary standing view. The disease infects various species of mammals however, from an economic point of view, tsetse-transmitted trypanosomosis is particularly im¬portant in cattle Meberate et al. [2]. The parasite is transmitted biologically by the tsetse fly (Glossina species) and infects animals over an area known as the ‘tsetse belt’, which extends approximately 10 million km2 across 37 countries in Africa, from the Sahara Desert in the North to South Africa in the south Ilemobade [3].

African Animal Trypanosomosis (AAT) occurs where the tsetse fly vector exists in Africa, between latitude 15°N and 29°S. Tsetse flies are hematophagous insects of the family Glossinidae and are biological vectors of African trypanosomosis in both animals and man the disease also trans¬mitted mechanically by biting flies, among which Tabanids and Stomoxy’s are presumed to be the most important. Clinical signs are not pathognomic and hence clinical examination is of little help in pinpointing the diagnosis. Infected animals show progressive loss of appetite, body weight, oedema of lower parts of body, intermittent fever, bilateral enlargement of prescapular lymph nodes, corneal opacity, salivation, lacrimation and abortion Taylor et al. [4]. Diagnosis is often based on history of chronic wasting condition of cattle in contact with tsetse flies.

Trypanosome can be confirmed parasitologically by demonstrating parasites in blood of infected animals and various techniques are available. In practice, many field programs of monitoring cattle for infection is based on routine screening of stained thick and thin blood films, thick films are examined to detect infected animals and thin films determine the species of infecting trypanosomes Andrews et al. [5]. Trypanosomosis is a major constraint contributig to the direct and indirect economic losses to crop and livestock production Abebe [6]. It is a severe problem to agricultural production in widespread areas of the tsetse infested regions that accounts over 10 million square kilometres of the tropical Africa. Non-tsetse transmitted trypanosomosis also affects considerable number of animal populations in tsetse free zone of the country STEP [7].

In Ethiopia, Trypanosomosis is widespread in domestic livestock in the Western, South and South-western lowland regions and the associated river systems i.e. Abay, Ghibe Omo and Baro/ Akobo Abebe and Jobre [8]. Currently about 220,000 Km2 areas of the above mentioned regions are infested with five species of tsetse flies namely Glossinapallidipes, G. morsitans, G. fuscipes, G. tachinoides and G. longipennis NTTICC [9]. Trypanosoma congolense, T. vivax, and T. brucei are most important in cattle with 14 million heads at risk in Ethiopia Upadhayaya [10]. Out of the nine regions of Ethiopia five (Amhara, Benishangul-gumuz, Gambella, Oromia and SNNPR) are infested with more than one species of tsetse flies Keno [11] Tesfaye [12]. Eventhough, trypanosomosis is economically imporantant disease, no enough studies were done in Ethiopia and no study was done in Botor tolay district. Therefore, the present study aims at the following objectives;

a) To determine the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in selected areas of Botor tolay district.

b) To determine apparent densities of tsetse flies in the Botor tolay district.

Study Period and Area

The study was conducted from November, 2017 to may, 2018 in Botor tolay district, which is located in Jimma zone of Oromia Regional States, South Western Ethiopia.It is located about 445 kilometers from West of Addis Ababa. Geo¬graphically, Botor tolay town falls between 7oC ``N latitudes and 12oC``E longitudes. The study was conducted in five peasant associations namely; Madaa jalala, Kata boke, Yatu dhahe, Garangaraa and Urjii Oromia are sellected areas. The total land area covers 159km2 with altitudes of 900 to 3347 meter above sea level. The annual mean tem¬perature ranges from 25oC to 32oC and receives annual rainfall between 1200-2400mm. The human population of the district is both rural and urban 83,888 and 10752 respectively. The total of human population of the district is 94,640. The livestock popula¬tions of the district were estimated to be 2,191,138 cattle, 7700 sheep, 44,626 goats, 68,521 poultry, 272 horses, 385 mule and 68,92 donkeys. Crop and livestock sales are important source of income for all wealth groups CSA [13].

Study Animal

The study populations constituted were local zebu cattle (Bos indicus) from five peasant associations (PAs). The age of animals was determined by dentition Gatenby [14] and categorized into three age groups (Appendix 1). The body condition of animals was also grouped based on criteria described by Nicholson and Butterworth [14] and they also categorized into three groups (Appendix 2).

Sampling Methods and Sample Size Determination

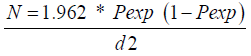

Random and purposive sampling methods were followed to select the study animals and study Sites respectively. The PA’s (peasant associations) were selected purposively due to their accessibility to transport and information from the district’s administrative body. The number of animals required for the study was determined using the formula given by Thrustfield [15] simple random sampling.

Where,

N = required sample size

Pexp = expected prevalence

d = desired absolute precision

The sample size was determined using 95% level of confidence, 50% expected prevalence since there was no previous study conducted in Botor Tolay district and 0.05 desired absolute precision. Therefore, a total of 384 cattle were included for this study.

Study Design

A cross sectional study was carried out to determine the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis and apparent fly density in five peasant association (Madaa jalala, Kata boke, Yatu dhahe, Garangaraa and Urjii Oromia) of Botor Tolay District of south west Jimma Zone, November 2017 to may 2018.

Study Methodology

Parasitological and Hematological Survey of Bovine Trypanosomosis:

a) Buffy Coat Technique: Blood was collected from an ear vein using heparinized micro-haematocrit capillary tube and the tube was sealed. A heparinized capillary tube containing blood was centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 rpm. After the centrifugation, trypanosomes were usually found in or just above the buffy coat layer. The capillary tube was cut using a diamond tipped pen 1 mm below the buffy coat to include the upper most layers of the red blood cells and 3 mm above to include the plasma. The content of the capillary tube was expressed on to slide, homogenized on to a clean glass slide and covered with cover slip. The slide was examined under ×40 objective and ×10 eye piece for the movement of parasite Paris et al. [16,17].

b) Thin Blood Smear: A small drop of blood from a microhaematocrit capillary tube to the slide was applied to a clean slide and spread by using another clean slide at an angle of 45°, air dried and fixed for 2 min in methyl alcohol, then immersed in Giemasa stain (1:10 solution) for 50 min. Drain and wash of excess stain using distilled water, allowed to dry by standing up right on the rock and examined under the microscope with oil immersion objective lens.

c) Measuring of Packed Cell Volume (PCV): Blood samples were obtained by puncturing the marginal ear vein with a lancet and collected directly into a capillary tube. The capillary tubes were placed in micro haematocrit centrifuge with sealed end outer most. The tube was loaded symmetrically to ensure good balance. After screwing the rotary cover and closing the centrifuge lid, the specimens were allowed to centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. Tubes were then placed in haematocrit and the readings were expressed as a percentage of packed red cells to the total volume of whole blood. Animals with PCV < 24% were considered to be anemic Murray [18].

d) Entomological Survey: A total of 52 monoconical traps were deployed in five peasant association of the district (12 in Madaa jalala, 10 in Kata boke, 10 in Yatu dhahe, 10 in Garangaraa and 10 in Urjii Oromia) at ap-proximate interval of 100-200m. All traps were baited with acetone, octenol and cow urine filled in separate bottles. After 48 hours of de¬ployment, tsetse flies in the cages were counted and identified based on their habitat and morphology to the genus and species level. Other biting flies were also identified according to their morphological structures such as size and proboscis at the genus level Uilenberg [18]. Tsetse flies were sexed just by observing the posterior end of the ventral aspect of the abdomen using hand lens. Male flies were identified by their enlarged hypopygium in the posterior ventral end of the abdomen. The apparent density of the tsetse fly was calculated as the number of tsetse catch/trap/day STEP [19].

Data Analysis

Row data on individual animals, parasitological and entomological examination results were inserted into Micro-Softe excel spread sheets to create a data-base and transferred to Statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 20.0 software program for data analysis. Descriptive statistics was used to determine the prevalence of trypanosomosis in cattle and Chi square test (χ2) was used to assess associated between trypanosome infection and risk factors or variables (age, sex, body condition and origin / peasant association). Student t-tests were used to compare mean PCV of study animals. In all analyses, the confidence interval level (CI) was 95% and P value P<0.05 was considered as significance. PCV was categorized as anemic if it is less than 24% and normal if it is greater than 24% Van den Bosseche and Rowlands [20]. The density of fly population was calculated by dividing the number of flies caught by the number of traps deployed and number odays of deployment and expressed as Fly/ Trap/ Day Pollock [21].

Prevalence of Trypanosomosis

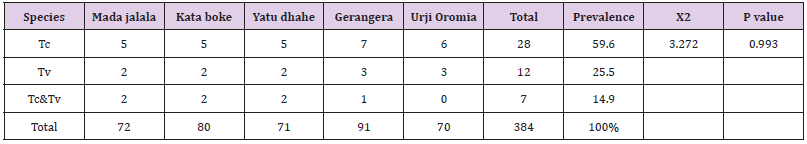

A total of 384 cattle blood sample were examined to determine the presence of trypanosomosis by Buffy coat technique and thin blood smear. Trypanosomosis were detected in 47 cattle with an overall prevalence of 12.24%. The prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis within the five PAs were 9(12.5%) at Mada jalala, 9(11.25%) at kata boke, 9(12.67%) at Yatu dhahe, 11(12.1%) at Gerangera and 9(12.8%) at Urji Oromia. Among species of trypanosome, Trypanosoma. Congolense 28(59.6%) was the most prevalent trypanosome species followed by T. vivax 12(25.5%) and mixed infection of T. congolense and T. vivax 7(14.9%) (Table 1). The prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in females and males were 26(15.95%) and 21(9.5%), respectively. Though the prevalence of trypanosome infection was higher in female than in males there is no statistically significant difference (p>0.05) between the two sex groups.

Table 1: The overall Prevalence of trypanosomosis in five PA’s with trypanosome species at botor tolay district.

Tc: trypanosome congolense, Tv: trypanosome vivax, Tc and Tv: mixed.

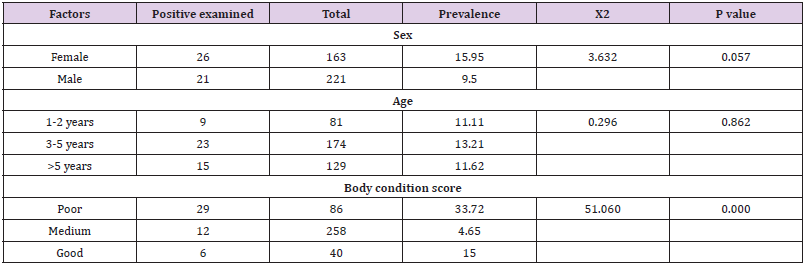

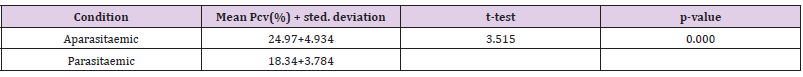

The prevalence of trypanosomes infection differed between age categories less than two year (<2 year), three up to five year (3-5years) and greater than five years (>5 years) but not significant (P>0.05). Higher prevalence were observed in the age of (3- 5) years with prevalence of 23 (13.21%) and lower in age <2year and >5. The prevalence trypanosomes in body condition score shows significant association with high prevalence found in poor 29(33.72%) (P<0.05) (Table 2).The mean PCV values of parasitaemic and aparasitaemic cattle were 18.34 and 24.97 respectively. There was a significant difference between PCV value of parasitaemic and aparasitaemic cattle.

Entomological Results

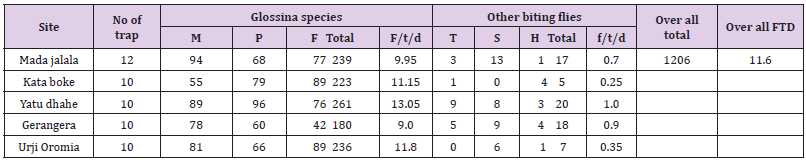

A total of 52 monoconical traps were placed approximately 100-200m apart and left in position for two consecutive days (48 hrs). The average tsetse fly density in the area was 1139(10.9 F/T/D) and the overall prevalence of this study was 1206 (11.6%) were flies were caught during the study period were Glossina species and other biting flies. G. morsitans 397s(3.81%), G. pallidipes 369(3.54%), and G. fuscipes 373(3.58%). 36(0.34%), 13(0.13%) and 18(0.18%) were Stomoxys, Hematpota and Tabanus, respectively. The flies caught per trap were identified, counted and apparent fly density per trap per day (f/t/d) was recorded. The tsetse flies were identified to species level Marquardt et al. [22].

The present study revealed that from a total of 384 randomly selected cattle’s in the study area, 47 (12.24%) of animals were positive for trypanosomes. Similar findings of 12.41% in Metekel and Awi zones of northwest Ethiopia Solomon & Fita [23]. But this is lower than previous reports: 20.40% in Wolyta and Dawero zones of southern Ethiopia Miruk et al. [24]. The relatively low prevalence of trypanosomosis in this study may be related to tsetse distribution and low fly–animal contact and parasite and vector control programmes practiced in the area by Bedele NTTICC annually (Appendix 3). Every farmer in tsetse belt are well aware of the disease and trypanocidal drugs used. The prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis between kebeles (PAs) was found to be not significantly different this might be due to the similarity in agro ecology, vegetation and environment of research areas.

The research showed that out of 47 positive cattle for trypanosomosis, T. congolense was found to be the causative agent in 59.6% (n=28), T. vivax 25.53% (n=12)and mixed infection accounted for 14.9% (n=7). The predominate species causing bovine trypanosomosis was T. congolense and this finding agreed with previous report from south-western Ethiopia by Abebe & Jobre, [8], Zecharias & Zeryehun, [25], Teka et al. [26], Duguma et al. [27]. This might be because the research area is suitable for the multiplication of biological vector (tsetse flies). Vector born trypanosome species are disseminated in most parts of Western and South Western parts of Ethiopia Abebe [28], Mulaw et al. [29]. Meanwhile, the current finding disagrees with Nabulime et al. [30] in Mulanda, eastern Uganda.

The occurrence of disease in three different body condition (poor, medium and good) animals shows the highest prevalence in poor body condition (33.72%) followed by in medium (4.56 %) and good body condition (15%) (Appendix 4). The finding showed that infection rates in poor body condition animals were significantly higher than that of medium and good body condition animals (Table 2). This is due to poor body condition animals are susceptible to the infectious disease. The reason behind is may be due to reduced performance of the animals created by lack of essential nutrients and poor management by the animal owner. In contrast, trypanosomosis is a chronic disease as stated by Urquhart et al. [31], the observed emaciation and weight loss might be caused by the disease itself. The varation between the medium and good body condition is due to the large sample size grouped under medium body condition (Table 3). This result agreed with previously reported findings by Girma et al. [32], Teka et al. [28], Fayisa et al. [33] and Bitew et al. [34].

Table 2: Prevalence of Trypanosomosis between Sex, age group and body condition score.

Table 3: Prevalence of trypanosomosis in different Pcv of cattle.

The mean PCV value of trypanosome positive animals was significantly lower (18.34 ± 3.784 SE) than that of negative animals (24.97 ± 4.934 SE). This finding is aligned with previous works by Ali & Bitew [35] and Rowlands et al. [36]. This is due to the contribution of trypanosomosis for causing anemia in infected animals. This finding agreed with previous reports by Tewelde [37] in western Ethiopia and Desta [38] in upper Dedesa valley of Ethiopia. In the absence of other diseases causing anemia, a low PCV value of individual animals is a good indicator of trypanosome infection Abebe [6] Marcotty et al. [39]. This study indicated that from 52 monoconical traps deployed in the study area for 48 hours, a total of 1206 flies were trapped among this flies 397 G. morsitans, 369 G. pallidepes, 373 G. fuscipes and 67 other biting flies were trapped. The overall 11.6 flies/trap/day apparent density of the tsetse flies was recorded in botor tolay district (Table 4). This finding is lower than the previous report 19.14 flies/trap/day in Daramallo District by Ayele et al. [40] and 14.97 flies/trap/day reports in selected villages of Arbaminch by Wondewosen et al. [41-50]. This difference could be attributed to environmental conditions, agro ecological differences and the season in the study area. The presence of other biting flies are playing important role in the non-cyclical transmission of trypanosomosis in the study area [51-70].

Table 4: Apparent density of flies in the district according to peasant association.

Morsitans(M), pallidipes(P), fuscipes(F), Tabanus(T) Stomoxys(T) & Hematpota(H)

Trypanosomosis is a major constraint contributig to the direct and indirect economic losses to crop and livestock production in Africa as it causes a serious and often fatal disease of livestock mainly in the rural poor community and rightfully considered as a root cause of poverty in the continent. Despite the importance of livestock to the larger sector of the population and to the economy at large the sub sector has remained untapped [71-80]. This study results revealed that bovine trypanosomosis and apparent tsetse density survey in five peasant association in fertile areas of botor tolay woreda in Jimma Zone indicated that an overall 12.24% prevalence of the disease and density of tsetse flies with an overall apparent density of 11.6 flies/trap/day. The major species of trypanonosomes identified in the study area were T. congolense and T. vivax .identification on entomological survey shows three species of tsetse fly identified was G. morsitans, G. pallidepes and G. fuscipes. Higher prevalence of trypanosomosis infection was observed in animals with poor body condition and low Pcv animals also found to be found significant compare with other risk factors age and sex which statistically insignificant [81-95]. Based on the conclusion, the following recommendations are forwarded:

a. Attempt should be made to expand government and private veterinary services to serve the community in the study areas.

b. The government and the community should continue their effort of controlling the major vectors of the disease, Glossina spp, by all available means proved to be effective.

c. Further researches directed at the discovery of better diagnostic technique suitable for the local condition should be encouraged to effectively monitor the efficacy of the control measures being implemented.

Histological and Histochemical Methods for Staining of Insulin: A Comparative Analysis-https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/2020/12/histological-and-histochemical-methods.html

More BJSTR Articles : https://biomedres01.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.